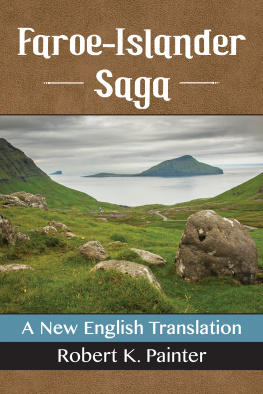

Faroe-Islander Saga

A New English Translation

Robert K. Painter

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

ISBN 978-1-4766-2326-9 (ebook)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2016 Robert K. Painter. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image of the Faroe Islands 2016 Jason Row/iStock/Thinkstock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Lucy,

Queen of Argyll, Ross,

and the Western Reaches

Preface

This book presents a new English translation of Faereyinga saga, or Faroe-Islander Saga, one of the lesser known Icelandic sagas, written by an anonymous author in Iceland sometime in the early 13th century. The central plot of the saga presents the history of the first settlers in the Faroe Islands in the early 9th century during the Viking Age, focusing on the feud between two rival chieftains, Sigmundur Brestirsson and Thrandur of Gta. This new literary translation aims to make Faroe-Islander Saga accessible to a wider readership in English, as this little read medieval work is just as engaging and profound as more commonly known Icelandic sagas such as Njals Saga, Laxdaela Saga, or Grettirs Saga. The translation is faithful enough to the original saga text to be used as a reference for students learning to read Old Icelandic, but fluid enough to be accessible for any reader with a general interest in the Norse world and the Icelandic sagas. The English text is accompanied by a brief introduction which provides an overview on the saga and saga-writing, the Faroe Islands during the Viking Age, and some literary themes in the work. Also provided are brief explanatory notes highlighting cultural and historical aspects of the text; chronological tables; genealogies of families; as well as maps illustrating the Faroe Islands, the geography of the North Sea in the Norse World, and an overview of medieval Scandinavia.

The impetus for this new translation of an obscure Icelandic saga came almost ten years ago when I was a graduate student in linguistics at the State University of New York at Buffalo. I was taking a seminar in sociolinguistic research methods from the venerable Professor Wolfgang Wlck, one of the Grand Old Men in the field of sociolinguistics, who proposed that I research the linguistic profile of these islands between Shetland and Iceland, where unstable bilingualism exists between the colonial Danish, the globally threatening English, and the local Scandinavian dialect, Faroese. Having just completed a yearlong training in linguistic fieldwork, I found my head filling excitedly with grandiose ideas of completing a dissertation under Professor Wlck, punctuated by self-important research trips to the remote Faroe Islands to collect data, myself jammering heroically to the locals in a fluent, educated Danish or Faroese (languages which I did not and do not speak). But somewhere during that heady spring of 2007, two important things happened. First, scouring for books on Scandinavian languages among the dusty shelves of the university library, I found a battered copy of George Johnstons translation of Faereyinga saga from 1994, misleadingly titled Thrand of Gotu. The language was stilted, and the sentences were short, declarative, and dry; but the story gnawed at my imagination. It wasnt long afterward that I tracked down the original text from the formidable slenzk Fornrit series and began to translate. Then, the second thing happened: our daughter Lucy joined us in the world in September 2008. Notions of a doctoral dissertation based on sociolinguistic field data from the Faroe Islands were transmuted into a very different kind of library based study on the historical phonology of Germanic and Italic languages. The Icelandic sagas remained on my mind, however, and a highlight of a trip to Iceland in 2013 including visiting the wonderful Saga Museum in Borgarnes.

Reading the various Icelandic sagas, first through English translations and eventually in the Old Icelandic, I was hooked. Many arguments can be made for the intrinsic value of studying the sagas as Icelands great contribution to world literature, or as important historical sources, but I follow the sentiment of two early 20th century University College London scholars, William Ker and Peter Foote, who explain their choice of Icelandic subjects as merely a love of stories (see Foote 1965, 9). The stories in the sagas are wonderful in their sober, matter-of-fact portrayal of their events, where the heroes are characterized by what they do, not what they say. Take two specific examples from Faroe-Islander Saga. In an early scene, two servants, Einar and Eldjarn, are sitting around a campfire idly discussing which of their kinsmen are the better men; a difference of opinion prompts Eldjarn to grab a brand from the fire and bash Einar on the shoulder with it; the following text states matter-of-factly, and Einar took it badly; he grabbed an axe and struck Eldjarn in the head (Chapter 5). The text does not say that Einar whined or considered his wounds or became angry or swore foully; rather the reader is simply invited to put himself in Einars position and to consider the logical thing to do after being hit by a flaming stick. The action of seizing ones axe in rage seems wonderfully natural and almost inevitable in this context. In a later scene from the saga (Chapter 38), a band of Sigmundurs enemies makes a surprise attack against his farm when, unbeknownst to them, he is not at home; at the moment when the men are kicking down the door, the saga reads, the lady of the house, Thurid, snatched hold of a sword and fought along with the household men. Again, it is not explicitly stated that Thurid fights as befits the wife of a great hero like Sigmundur, or that it might be in some way unusual for a woman to join the fight. Rather, all that is said about when her foes broke down the door is that Thurid went for her sword. The characterization of her bravery is read in Thurids actions, never expressed directly. In the Icelandic sagas, this device of letting the facts speak for themselves and leaving out the commentary makes for rich storytelling, where the plot is driven relentlessly by a concatenation of one event, followed by the next.

With this new literary translation of the Faroe-Islander Saga, I tried to capture this sense of intrinsic energy and dramatic storytelling from the Old Icelandic original, something I felt was diluted or lacking from those rare, previous translations of this saga into English (see A Note on the Translation following the Introduction). This translation is fully original and dependent on none of the previous English translations. By attempting a novel start, I hoped to provide a fresh take on this lesser-known classic of the canon of sagas, something that was stylish and readable to a modern audience while still very faithful to the letter and spirit of what the saga-writer intended.

I would like to thank several people who contributed to the success of this project. Colleagues in the Linguistics Program at Northeastern University were constantly supportive and smilingly upbeat at all the right times, particularly Adam Cooper, Heather Littlefield, and Neal Pearlmutter. A special note of appreciation is also given to professors Thalia Pandiri and Craig Davis of Smith College, who were both supportive of my translation project.

Next page