Robert Cook (transl.) - Njal’s Saga

Here you can read online Robert Cook (transl.) - Njal’s Saga full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2001, publisher: Penguin Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Njal’s Saga

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books

- Genre:

- Year:2001

- City:London

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Njal’s Saga: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Njal’s Saga" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Njal’s Saga — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Njal’s Saga" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

NJALS SAGA

Born and raised in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Robert Cook was educated at Princeton, Zurich and Johns Hopkins and taught English medieval literature at Tulane University in New Orleans for twenty-seven years. In 1990 he moved to Reykjavk to serve as Professor of English Literature at the University of Iceland. He has published on English medieval literature and on the Icelandic sagas, and together with Mattias Tveitane edited Strengleikar (1979), an Old Norse translation of twenty-one medieval French lais.WORLD OF THE SAGAS Editor rnolftir ThorssonAssistant Editor Bernard Scudder Advisory Editorial Board: Theodore M. Andersson Stanford University

Robert Cook University of Iceland

Terry Gunnell University of Iceland

FredrikJ. Heinemann University of Essen

Viar Hreinsson Reykjavik Academy

Robert Kellogg University of Virginia

Jnas Kristjnsson University of Iceland

Keneva Kunz Reykjavik

Vsteinn lason University of Iceland

Gsli Sigursson University of Iceland

Andrew Wawn University of Leeds

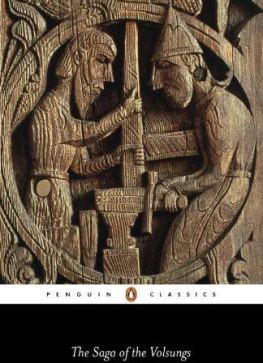

Diana Whaley University of Newcastle NJALS SAGA Translated with Introduction and Notes by ROBERT COOK PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc.,375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, US A

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4v 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11, Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Private Bag 102902, NSMC, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England This translation first published in The Complete Sagas of Icelanders ( Including 49 Tales ) III, edited by Viar Hreinsson (General editor), Robert Cook, Terry Gunnell, Keneva Kunz and Bernard Scudder Leifur Eirksson Publishing Ltd, Iceland 1997

First published in Penguin Classics 2001

Translation copyright Leifur Eirksson Publishing Ltd, 1997

Introduction and Notes copyright Robert Cook, 2001

All rights reserved The moral rights of the translator have been asserted Leifur Eirksson Publishing Ltd gratefully acknowledges the support of the Nordic Cultural Fund,

Ariane Programme of the European Union, UNESCO and others. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 9781101488263

Contents Acknowledgements Special thanks are due to Sverrir Tmasson and other learned scholars at the RNi Magnisson Institute in Reykjavk, to Icelandair, to Professor Jn Frinsson of the University of Iceland, to Gurn Inglfsdttir, and to my copy-editor, Elizabeth Stratford. So many others have helped me in one way or another that in mentioning the following I beg indulgence from those I may have temporarily overlooked: Carol Clover, Gerda Cook-Bodegom, Helle Degnbol, Susanne Eisner-Kartagener, Davi Erlingsson, Henry Frey Galina Glazyrina, Terry Gunnell, Fritz Heinemann, Viar Hreinsson, rmann Jakobsson, rnolfur Thorsson prepared the maps, genealogies and glossary, and Jn Torfson the index of characters. Bernard Scudder, Robert Kellogg, Helga Kress, William I. Miller, Hermann Plsson, John Porter, Christopher Sanders, Marianne Kalinke, Andrew Wawn and Yelena Olegovna Yershova. Introduction Njals Saga is by far the longest of the forty family sagas written in Iceland in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and over the years it has proved to be the favourite. The saga teems with life and action, with memorable and complex characters from the heroic Gunnar of Hlidarendi, a warrior without equal who dislikes killing, to the villainous, insinuating Mord Valgardsson, who turns out to be less dastardly than we first expect. Unforgettable events include Skarphedins head-splitting axe blow as he glides past his opponent on an icy river bank, or Hildigunns provoking of her uncle to seek blood revenge by placing on his shoulders the blood-clotted cloak in which her husband was slain. In Njals Saga we read of battles on land and sea, failed marriages, divided allegiances, struggles for power, sexual gibes, malicious backbiting, revenge, counter-revenge, complex legal processes and peace settlements that fail to bring peace, not to mention dreams, portents, prophecies, a witch-ride and valkyries. Behind all this richness lies a well-crafted story of decent men and women struggling unsuccessfully to control a tragic force propelled by persons of lesser stature but greater ill-will. Just as in the Norse poem Vlusp (The Seeresss Prophecy) the gods met their doom (no mere twilight) at the hands of brute giants and monsters, after which a new and peaceful earth arose, so do the terrible events of Njals Saga lead finally and at great cost to a dignified resolution bearing the promise of a better time. BACKGROUND From the time they adopted the Latin alphabet in the eleventh century, the Icelanders have been prodigious writers and record keepers. Among the many genres that have been preserved is a group of annals, begun around the year 1200, most of which contain, usually under the year 1010, the simple entry Nials brenna (the burning of Njal). Another work, which dates back to the twelfth century, The Book of Settlements , a detailed account of the people who settled Iceland in the late ninth century, reports this about a man named Thorgeir: His son was Njal, who was burned to death in his house. Some versions of The Book of Settlements add at Bergthorshvol and the number of men (varying from seven to nine) who were burned to death. Snorri Sturluson, the great thirteenth-century writer and man of affairs, ascribes a half-stanza in his Edda to Brennu-Njll (Njal of the burning) and The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue reports that the general assembly held after the burning of Njal was one of the three most heavily attended Althings of all time.Thus a number of sources which pre-date Njals Saga , in several of the genres of medieval Icelandic literature, testify to the fact that around the year 1010 the buildings at a farm named Bergthorshvol in the south of Iceland, on a marshy area dotted with hillocks and bordering the ocean, were set on fire and burned. Inside were the farmer, a man named Njal Thorgeirsson, and some others. The references to this burning make it one of the best documented events of the so-called saga age in Iceland (9301030), and there is no reason to question it as historical fact.Another prominent event in Njals Saga (or Njla , to use its popular nickname) is supported by external sources. A stanza in the twelfth-century poem slendingadrpa by Haukur Valdsarson records that a man named Gunnar defended himself against an attack by a certain Gizur, and managed to wound sixteen men and kill two. This event is also mentioned in The Saga of the People of Eyri and in The Book ofSettlements , and it seems safe to conclude that this too was a historical fact.These two events, the attack on Gunnar at Hlidarendi and the burning of Njal at Bergthorshvol, constitute the two principal climaxes of Njals Saga . There is a huge gap, however, between the bare saga-age events and their elaboration in the prose masterpiece we have before us, written around 1280. As with the Homeric epics and the Song of Roland , well-remembered historical events were passed down through several centuries of oral tradition and finally shaped by the hand of a master story-teller and writer into a non -historical work of art. The author of Njals Saga was not trying to write history, but to create his own dramatic fiction, using events and persons known to him but going far beyond them with his own inventions and interpretations. There was a man named Njal who was burned to death in his home around the year 1010, and a man named Gunnar who was killed by men who attacked his home around 992 but they are not the Njal and Gunnar of the thirteenth-century Njals Saga .In Icelandic the word saga means both history and story, and if Njals Saga represents inspired story more than remembered history, it does not exist in isolation, is not a beginning or an end in itself. It is the longest, among the latest, and arguably the best of a group of forty sagas written anonymously in Iceland in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries about people who lived there in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Among these Sagas of Icelanders (also known as family sagas) there is a remarkable consistency, owing largely to the long period of oral transmission. For one thing, many characters overlap from saga to saga, and are mentioned as well in The Book of Settlements . The family of Hoskuld Dala-Kolsson, introduced in the first chapter of Njals Saga and prominent in the first half of the saga, is the principal family in The Saga of the People of Laxardal . The lawspeaker Skafti Thoroddsson (first introduced in Ch. ) appears in other family sagas as well as in historical works, as does Thorgeir the Godi of Ljosavatn, who played a key role in the adoption of Christianity. Many other characters in Njals Saga are known from other Sagas of Icelanders, including rulers of Scandinavia like Harald Grey-cloak, Hakon Sigurdarson and Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, and Earl Sigurd Hlodvisson of Orkney. The multiple appearance of characters is so common in early Icelandic literature that the notes to this tradition occasionally record that a certain character, for example, Gunnars brother Kolskegg, does not appear in other sources. This may seem gratuitous information, and it is certainly no guarantee that the character is non-historical, but in some cases it may suggest that a person has been deliberately invented, either in the process of oral re-telling or by the late thirteenth-century author.A second way in which the Sagas of Icelanders display consistency is their use of a common body of narrative motifs. Scandinavian kings and earls appear frequently because it is de rigueur for a promising young Icelander to establish his credentials by visiting foreign rulers and making a favourable impression on them, whether by composing a poem of praise or excelling in games or defeating the kings enemies. The triumphant journeys abroad of Hrut (Chs. 26) and Gunnar (Chs. 2932) are two among many such in the corpus. Other motifs common to Njals Saga and other Sagas of Icelanders are the refusal to sell (as in Ch. 47), the horse fight, the broken shoelace, quests for support, dissemination of important information by itinerant women or other unnamed characters, the use of spies, and, last but not least, the goading woman who incites a man, usually a kinsman, to take blood vengeance for a slight to the familys honour. Such common motifs, together with the time and place (Iceland in the tenth to eleventh centuries), the subject matter (primarily feuds and their resolution), character types, standardized descriptions of battles and feasts, common thematic concerns and the general social setting, make the Sagas of Icelanders a homogeneous literary genre.The social setting is so consistently presented that we can think of it as a third major defining feature of the Sagas of Icelanders. Recent saga scholarship with an anthropological and sociological focus has in fact demonstrated that although the sagas are not to be trusted as history in the narrow sense (names, dates, events), they provide a remarkably coherent picture of an intricate legal and social system, one which saw little change over the three centuries of the commonwealth (9601262). For this kind of history dealing with matters such as the organization of a hierarchical society, the arranging of marriages and divorces, the obligations within the kin group with respect to feuds, and the handling of disputes (whether by the courts or by personal arrangement) the sagas represent a large body of shared material so consistently that it cannot have been invented by any individual author. For details of the social setting see the Glossary, especially under Althing, Fifth Court, full outlawry, godi and Lawspeaker.A fourth way in which the Sagas of Icelanders form a generic whole is their firm setting in historical time and their unified view of Icelands evolving past. Many sagas though not Njals Saga begin by mentioning the reign of Harald Fair-hair (r. 870930), the first king to bring all of Norway under his control. The Saga of Hrafnkel Freys Godi , for example, begins: It was in the days of King Harald Fair-hair that a man named Hallfred brought his ship to Breiddal in Iceland, below the district of Fljotsdal. The common explanation in the sagas for the emigration of prominent families from the west coast of Norway is the desire to escape Haralds harsh rule, although in fact other reasons, such as over-population, were just as likely. Many of those who left Norway stopped first in Celtic territories in Britain and later brought women and slaves out to Iceland, so that the population was not pure Scandinavian. The flight from Norway led to the land-taking or settlement of Iceland, an island previously uninhabited except for a few Irish monks, who soon left when they saw themselves deprived of the solitude that had drawn them there. It is reckoned that by the year 930 the population of the new land had reached at least 20,000.In addition to this foundation story of flight and settlement, the historical awareness of the thirteenth-century Icelander would have included the importation of laws from Norway by a man named Ulfljot and the establishment of the Althing (general annual meeting), both around the year 930; a refinement of the laws by a division of the country into four quarters, around 965; the acceptance of Christianity at the Althing in 999 or 1000; and the establishment of the Fifth Court in the year 1004. All of these facts, from Harald Fair-hair to the Fifth Court and beyond, were set down around 1125 in a concise book by Ari Thorgilsson known as The Book of theIcelanders . Not every Icelander in the thirteenth century had a copy of Aris book, or knew the precise dates and details just outlined, but it is clear that the family sagas were written for an audience possessed of a lively knowledge of the historical development of their country and its institutions. Njals Saga does not mention the flight from Harald Fair-hair, but it embodies the historical legend by including two of the principal events the Conversion (Chs. 100105) and the establishment of the Fifth Court (Ch. 97) and by incorporating, as do most of the family sagas, the detailed genealogies common to the genre of historical writings. Ari Thorgilsson mentions an earlier, expanded version of his short book, which contained Genealogies and Lives of the Kings, and there is other evidence that written genealogies were among the earliest secular writings in Iceland. Whether written or simply preserved in oral family tradition, a knowledge of ones ancestors and of the kinship relations of prominent figures was built into the consciousness of every Icelander. Njla begins by mentioning Mord Gigja and his father Sighvat the Red (his grandfather, according to The Book of Settlements ). The next person introduced is Hoskuld Dala-Kolsson, and his line is traced back through his mother to a prominent female settler in the west of Iceland, Unn the Deep-minded. The text does not specify that Sighvat and Unn were settlers this is not necessary, for the audience of the saga would have known this. Genealogies usually appear in the sagas when a character is introduced, often in combination with an insightful description.Tracing of family lines goes forward as well as backward. The twelfth-century Icelandic historian, Saemund Sigfusson the Learned, is mentioned in Njals Saga as a descendant of Ulf Aur-godi (Ch. 25) and also of Sigfus Ellida-Grimsson (Ch. 26). Gizur the Whites son Isleif, mentioned in Ch. 46, became the first bishop of Iceland in 1056, and the audience would have known that Isleifs son was the influential Bishop Gizur who introduced the tithe to Iceland. In the fullest genealogy in the saga, that given for Gudmund the Powerful in Ch. 113, his line is traced not only to Bishop Ketil (d. 1145) but to the prominent thirteenth-century families of the Sturlungs and the people of Hvamm. The abundant genealogies, not to mention the abundance of characters, must have made Njla a rich shared experience for thirteenth-century Icelanders, most of whom could trace their ancestry back to at least one of the four hundred settlers and to other persons named in this and other sagas.In this sense, the modern reader unless he is an Icelander who can trace his lineage for a thousand years (as many can) is an outsider, unable to share fully in the personal excitement of reading about ones family past and ones national past. There is no disadvantage, however, if the reader is prepared to understand sympathetically the historical background just described and what it must have meant to the men and women who wrote and read or listened to these sagas in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It is well documented that the thirteenth century in Iceland was an ugly and troubled time, virtually a period of civil war, with large-scale battles, with power falling into fewer and fewer hands (instead of being distributed among the thirty-nine godis) and with interference from Norway in both secular and ecclesiastical affairs. The resolution of this turmoil was submission to Norwegian rule in the year 1262, and it was seven centuries before the Icelanders became an independent nation again, in 1944. Whether written before 1262 or after (like Njals Saga ), the sagas were written partly out of a need to affirm identity, both personal and national, with the past, a time when their ancestors fled Norwegian tyranny rather than succumb to it and built up a new society free of monarchical rule and governed by laws and institutions that functioned with dignity, if not without bloodshed. THE SAGA We have seen that the author of Njals Saga worked with traditional materials, oral tales of historical (and non-historical) events and persons, combined with a strong consciousness of his countrys history and social institutions. He apparently also worked with written sources, including genealogies, a book of laws, accounts of the Conversion (Chs. 100105) and of the battle of Clontarf (Chs. 1537) and works in Icelandic based on foreign sources such as the Dialogues ofGregory the Great (see the note to Flosis dream in Ch. 133). It is impossible to disentangle the four components in the saga authentic history, the inventions of oral tradition, written sources and the contribution of the thirteenth-century author but the saga shows so many signs of careful artistry that one is inclined to believe in a master craftsman at the final stage, perhaps even a writer who, as the Swedish poet and critic A. U. Bth put it long ago, had the last line of his saga in mind when he wrote the first.The last sentence of the saga in most manuscripts refers to it as Brennu-Njls saga , which can be translated either the saga of the burning of Njal (with an emphasis on the act of burning) or the saga of Njal of the burning (i.e. of Njal who endured the burning). In either case this term (used as the title in most modern editions) points to the two things which are central, a man and a burning. The laws make it clear that burning a mans house was a heinous crime, punishable by full outlawry even if no persons were burned ( Laws of Early Iceland , p. 169). The saga itself shows burning to be shameful as well as heinous. In the attack on Gunnar in Ch. 77, the option of burning was proposed by the malicious Mord Valgardsson, but firmly rejected. In the attack on Bergthorshvol, Flosis own words before starting the blaze reveal his awareness of the shame attendant on such a deed (Ch. 128). The saga, like the tradition behind it, was fascinated by this horror. In one way or another all the events in the first part of the saga lead to the non-incendiary killing of Gunnar; all of the subsequent events, as well as many of the earlier events, lead to Njals death by burning. After this climax there are still twenty-nine chapters in the saga (13159); these are more than a coda, they are a necessary settling of scores and a hard-won return to equilibrium.The man Njal is not the hero one expects from a work called saga. His introductory description (Ch. 20) shows him to be an older man (or at least a man with grown children, as becomes clear in Ch. 25), known for his wisdom, his gift of prophecy, his skill at law, and a surprising physical detail his inability to grow a beard. Further, the beardless titular hero of this saga never kills, never fights, and is only once shown to carry a weapon, a rather useless short axe (Ch. 118). His neighbour and good friend Gunnar, on the other hand, is the very model of the blond, blue-eyed Viking, described chiefly in terms of his unmatched physical skills (Ch. 19). His two battles against Viking raiders abroad (Ch. 30) prove him to be the greatest of Icelandic fighters. His tragedy is that back in Iceland he is dragged into quarrels with men of inferior worth who envy his greatness and eventually bring him down. Njal and Gunnar form an ideal complementary pair, wisdom and strength, and Gunnar profits from Njals advice and legal skills as long as he can and then, in effect, gives up.The presence of Njal at the centre of the saga is a sign that the emphasis is not on overt displays of masculine prowess, though of course there are a generous number of personal combats, carefully described with a connoisseurs eye to every movement, every swing of the sword and thrust of the spear, every gaping or severing wound. Many of these encounters, however, are not altogether heroic. Gunnar is on his own when he is attacked in his home by forty men, Hoskuld Thrainsson is killed in a cowardly attack by five men who lie in hiding until he comes out in the morning to sow grain, and Njal and his family are annihilated by men who take no risks and burn them inside their house. Much blood is shed in the saga, but much of it is shamefully shed not exactly what seekers after Viking adventure want to read.Rather than violent action, it is spiritual qualities that occupy the centre of interest in this saga intelligence, wisdom, decisiveness, purposefulness, a shrewd business sense, the ability to give and follow advice, decency, a sense of honour. Njal says at one point, when he is calculating how to respond to the abusive language of the Sigfussons, they are stupid men (Ch. 91). Those who plot evil, invent and pronounce gratuitous insults and envy the honest virtues of others are stupid. Between their stupidity and the clear-headedness of their antagonists lies the central conflict in the saga. It is emblematic that when Njal has a vision of some men about to attack Gunnar he reports that they seem in a frenzy but act without purpose (Ch. 69).In our age of self-doubt, identity crises and existential uncertainty, it is refreshing to read about firm decision-making and purposeful action by men and women with a sure sense of themselves. Hesitation is treated with scorn in Njla , as when Hallgerd whets Brynjolf in Ch. 38: he falls silent, and she insults him by saying that Thjostolf (now dead) would not have hesitated. When Sorli Brodd-Helgason gives a feeble response to Flosis request for support, Flosi says I can see from your answer that your wife rules here (Ch. 134). Some men of course are temporarily caught in a dilemma, like Flosi in Ch. 116, torn between blood vengeance and a peaceful settlement, or Ketil of Mork (Chs. 93 and 112) and Ingjald of Keldur (Chs. 116 and 124), torn between conflicting allegiances. Their decisions are not easy, and we sympathize with them. But we are thrilled by men who do not stop to weigh the odds, like Kari outside the hall of King Sigtrygg of Orkney in Ch. 155: when he overhears Gunnar Lambasons lying account of the burning, he dashes in and cuts off Gunnars head in a single blow. We also admire Gunnar of Hlidarendis change of mind: his decision to remain in Iceland rather than go abroad as an outlaw is taken quickly, resolutely and courageously (Ch. 75).The good characters not only understand themselves and what is required of them, they also know what to expect of others, and often with remarkable precision. The fullest example of this is Njals instructions to Gunnar in Ch. 22, where he is able to predict step by step exactly what will happen when Gunnar comes in disguise to Laxardal. A small example is Karis ability to time the movement of Ketil and his men (beginning of Ch. 152). In between are many other cases where intelligent people show a keen ability to anticipate the actions and words of others.A concentrated form of such intelligence is prophecy, a gift reserved for a special group, according to the statement in Ch. 114 that Snorri was called the wisest of the men in Iceland who could not foretell the future. An unusual number of persons in Njals Saga possess this gift. Njal is of course the main figure here. To mention just two examples: he knows that if Gunnar kills twice within the same bloodline and then does not keep the settlement for the second killing, he will be killed; he also knows, far in advance of the burning, what will be the cause of his death (Ch. 55). Hrut Herjolfsson is another man with prophetic power. In the opening chapter of the saga he is able to look at the young Hallgerd and predict both that many men will suffer because of her (and they do, not least Gunnar) and that she will steal (which she does). Hrut frequently makes wise predictions, as when he foresees that Gunnar will suffer for having taken Unns dowry by force, and that he will later turn to Hoskuld and Hrut for friendship (Ch. 24).Other characters too have their share of intelligent foresight: Glum knows in advance that Hallgerd will not have him killed (Ch. 13); Helgi Njalssons second sight enables him to see trouble in Scotland for Earl Sigurd (Ch. 85); the old woman Saeunn curses the chickweed which she knows will be used to set a fire at Bergthorshvol (Ch. 124); Bjarni Brodd-Helgason knows that the man who undertakes Flosis defence will die (Ch. 138). Many other examples will strike the readers attention. Whether plain intelligence or a special gift of prophecy, there is an impressive amount of clear thinking in Njla .Foresight and advice-giving go hand in hand, for the man who can predict the outcome of things is best equipped to give advice. Hrut and Njal are the two who most effectively and consistently combine these two skills. However, giving good advice is one thing, and following it is another. Gunnar, the chief beneficiary of Njals advice, is a clear-headed man with a good and non-violent nature (I want to get along well with everyone, Ch. 32), but he fails all too often to heed good advice and warnings. He follows to the letter Njals advice on how to reclaim Unns dowry (Ch. 23), Kolskeggs advice to offer Otkel compensation for the theft (Ch. 49) and Njals legal advice (Chs. 645). But he goes to the Althing against Njals wishes (Ch. 32); he neglects to take the Njalssons along with him to Tunga, as he had promised (Ch. 60); he declines Asgrims offer of company just before the ambush at Knafaholar (Ch. 61); he not only ignores Olaf Peacocks advice to travel in large numbers (Ch. 59), but declines Olafs invitation to move west to Dalir when his life is in greatest danger (Ch. 75); in his final scene he refuses his mothers advice not to shoot one of the enemys arrows back at them, and this contributes to his defeat (Ch. 77). Much of this may be regarded as part of the heroic code the hero stands alone, he defies his enemies but it is also imprudent.Most crucially, after he has killed twice in the same bloodline, Gunnar neglects to follow the second part of Njals advice: not to break the settlement made for the killing (Ch. 55, repeated in Ch. 73). By deciding to remain in Iceland (Ch. 75), thus breaking the settlement, Gunnar seals his own fate.There are a large number of proverbial sayings attributed to the characters in Njals Saga , over fifty, and some are repeated twice or even three times. They emphasize the importance of intelligent wisdom, and in nearly every case they are uttered by good and wise characters; an exception is Sigmund in Ch. 41, but when he, after being told by Gunnar to avoid Hallgerds advice, states that Whoever warns is free of fault, we can suspect insincerity, or even sarcasm, behind his words he quickly ignores Gunnars warning. Sometimes the proverbs have a resonance for the story as a whole, such as the twice-repeated statement that the effect of ones actions is often two-sided, or cold are the counsels of women, or the hands joy in the blow is brief (repeated three times). Akin to the proverb is the pithy saying, such as Rannveigs comment when she hears that Hallgerd is planning to have one of Njals servants murdered: Housewives have been good here, even without plotting to kill men (Ch. 36).One final form of intellectual activity telling the truth or lying needs to be mentioned, for it contributes significantly to the unfolding of the saga. In addition to his wisdom and prophetic powers, Njal is known as a truth-teller. Hogni Gunnarsson says of him that he never lies (Ch. 78), and similar statements are made on two other occasions. Hjalti Skeggjason and Runolf of Dal are also labelled as men who tell the truth, and many of the good characters, like Hrut and Hall of Sida, gain authority because they can be trusted. On the other hand there is some notable lying in the saga Skammkel lies to Otkel (Ch. 50), Thrain lies to Earl Hakon (Ch. 88), Mord lies to Hoskuld and to the Njalssons (Chs. 10910) and their lies always have evil effects.Telling the truth or its opposite forms an important part of the sagas large interest in reporting, telling news, spreading information. The saga as a whole claims at a number of places with expressions such as It was said that to be a true report of what, according to tradition, really happened. The author scrupulously interrupts his account of the battle at the Althing to say that though a few of the things that happened are told here, there were many more for which no stories have come down (Ch. 145). Within the saga there are constant references to what people are saying. The slaying of Gunnar was spoken badly of in all parts of the land (Ch. 77). Here they ended their talk, but this became a topic of conversation among many (Ch. 91). A persons honour depended on public opinion: when a settlement is made for Hallgerds theft and Skammkels lie, the narrator reports that Gunnar had much honour from this case. People then rode home from the Thing (Ch. 51). We understand that the settlement was reported all over the country by those who had been at the Althing, and that Gunnars reputation was enhanced in this way. The Iceland of Njals Saga is alive with talk, and pregnant with proof of the power of words.Unfortunately for the decent people in the saga, much of the talk is lies, and in particular slanderous lies about a mans effeminacy, which was inseparable from cowardice in the Old Norse way of thinking together they indicated that a man was not fully a man. The worst defamation of all was to say that a man was not merely effeminate, but in fact played a womans part in a homosexual relationship. Sexual slander against women consisted in a charge of lechery. Hallgerds comment on Bergthoras deformed fingernails (Ch. 35) may be an instance of this; a clearer case is Skarphedins calling Hallgerd either a cast-off hag or a whore (Ch. 91).It is regrettable that Mord Gigja made public the marital problems between Hrut and Unn, but at least no lie was told. Slander gets under way in Ch. 35, when Hallgerd calls attention to Njals beard-lessness, and it becomes deadly serious in Ch. 44 when Hallgerd invents the nicknames Old Beardless for Njal and Dung-beardlings for his sons, implying that their beards would not grow unless they put dung on their faces. Hallgerd gets Sigmund to compose verses on this theme, and of course these verses and Hallgerds epithets circulate. In retribution the Njalssons (i.e. sons of Njal) slay Sigmund, their first act of violence. Later, in Ch. 91, Hallgerd revives the epithets when tension between the Njalssons and the Sigfussons is at its highest, and again the Njalssons are provoked to swift and appropriate revenge. Ancient Norwegian law, and presumably Icelandic law as well, sanctifies blood revenge for sexual defamation.Since men are not supposed to weep in the world of the sagas, unlike the Homeric world, another form of sexual slander is to accuse a man of weeping. Skammkel spreads the word that Gunnar wept when Otkels horse ran at him (Ch. 53), and at the burning Gunnar Lambason taunts Skarphedin with weeping (Ch. 130). Later, in Orkney, when Gunnar Lambason falsely states that Skarphedin wept at the burning, he is immediately slain by Kari (Ch. 155).Two of the most highly charged scenes in this highly dramatic saga turn on sexual matters. When Hildigunn whets her uncle Flosi to take blood revenge for the slaying of her husband Hoskuld Thrainsson, she challenges him in the name of his courage and manliness, or else he will be an object of contempt to all men (Ch. 116). The word translated as manliness here could also be translated as masculinity Hildigunns insinuation is that Flosi will be less than a man if he fails this duty. In the scene at the Althing where a settlement has been made for the slaying of Hoskuld (Ch. 123), Flosi questions the gifts which Njal placed on the pile of compensation money and revives Hallgerds insulting epithet Old Beardless. Skarphedin responds with the coarsest and bluntest sexual insult in the saga, alluding to a rumour (no doubt an invented one) that Flosi is used as a woman by the troll of Svinafell (Flosis farm). This insult of course ends all hope of a peaceful settlement.One effect of all the slander, even though based on lies and distortions, is to destabilize the opposition between masculine and feminine that is typical of the family sagas. The slander calls attention to some realities a hero who cannot grow a beard, two heroes (Gunnar and Hrut) who in one way or another cannot satisfy their wives, and so on which challenge traditional male and female roles. Added to this is the fact that the events of the saga are more shaped by women than appears at first glance. Women are sometimes married without being consulted, and they occasionally serve as passive counters in the game of power, but the first eighteen chapters are determined by the desires and needs of three women, Queen Gunnhild, Unn and Hallgerd (who avenges herself for being married against her will); Bergthora and Hallberd plot the reciprocal killings in Chs. 3545, leaving their husbands to pick up the pieces; Hallgerds derisive epithets, as we have seen, provoke two major killings; and the whetting of Flosi by Hildigunn sets the course towards the catastrophical burning, rather than the peaceful settlement Flosi would otherwise have accepted. It would be nve to call Njals Saga a mans saga.If there is ambiguity in the treatment of sexuality, there is also ambiguity with regard to wisdom. The pessimistic tone of the saga derives largely from the fact that intelligent and good people (intelligence being a necessary part of goodness), making decisions of their own free will, cannot avert disaster. Worse, it appears that intelligence is uneven (as Hallgerd says of Njal in Ch. 44, derisively, but perhaps with a grain of truth). Time and again the actions of the wisest man in Iceland are the seeds of disaster. By helping Gunnar win back Unns dowry, he makes her marriage with Valgard possible, and the fruit of this marriage is Mord Valgardsson. By advocating the Fifth Court and thus procuring a godord for Hoskuld Thrainsson (Ch. 97), he makes Hoskuld a likely target for slaying. The very procedure he proposes for the Fifth Court concerning the reduction of the number of judges from forty-eight to thirty-six (Ch. 97) becomes the technicality by which the suit for the burning is quashed (end of Ch. 144). We have already mentioned his misguided gift (of a robe and pair of boots) at the settlement for the slaying of Hoskuld Thrainsson (Ch. 123). His final piece of advice, that his sons come inside the house at Bergthorshvol rather than face the attackers outside, seems almost perverse in view of the fact that he has foreseen the coming conflagration. Like Gunnar when he changed his mind about leaving Iceland, Njal just seems to give up. One of Icelands greatest saga scholars, Sigurdur Nordal, found the complication of goodwill and ill-fate, wisdom and failure so great in Njla that he called the saga a symbolic fable of the vanity of human wisdom.The ambiguities of sexuality and wisdom help to make Njla the richly complex saga that it is. A third kind of ambiguity has to do with character. None of the carefully sketched chief players the list includes Hrut, Hallgerd, Gunnar, Njal, Mord, Thrain, Hildigunn, Skarphedin, Flosi, Kari and Thorhall is a simple type. They combine good and bad, weak and strong, with all the three-dimensionality of real life. We have seen that Gunnar and Njal do not run to type. Thrain Sigfusson is Gunnars uncle and supporter, but compromises himself by agreeing to be present (though not participating) at the slaying of Njals servant, Thord Freed-mans son (Ch. 412). In Norway he is at first a loyal supporter of Earl Hakon (Ch. 82), but then deceives the earl when he decides to aid Hrapp (Ch. 88). Back in Iceland he joins his brothers and Hrapp and Hallgerd in abusing the Njalssons, though at the same time he tries to prevent the others from using the epithets Old Beardless and Dung-beardlings (Ch. 91). He seems to be a man with the right instincts, but too easily persuaded to go against them. Flosi is another example of a mixed character (the term is used of Hallgerd in Ch. 33). He is a godi, a forceful and highly respected man, but under great pressure he consents to lead others to the worst crime in the saga, the burning at Bergthorshvol. After the burning the saga very carefully builds up his character again.The word fate often comes up in discussions of Njla , and to some readers it may seem that the many accurate prophecies of the future and the many omens of disaster mean that the saga consists of a totally determined series of events. Frequent utterances like What is fated will have to be (Ch. 13) and Things draw on as destiny wills (Ch. 120) support this impression. Njal knows quite early what will be the cause of his death, Something that people would least expect (Ch. 55), and after the slaying of Hoskuld he predicts the death of himself and his wife and all his sons, and good fortune for Kari (Ch. III). Njals advice, as well as his outright prophecies, often has the force of a prediction. When he advises Gunnar not to kill twice in the same bloodline, for example, the reader knows that of course he will, and when Njal tells him that he will live to old age if he keeps the settlement (Ch. 74), the reader knows that Gunnar will break it, despite his two disclaimers (in Chs. 73 and 74). Warnings and advice are often the equivalent of predictions of violence. So too are goading scenes and changes of complexion it seldom happens that a goading, or suppressed anger, does not lead to violent action.The fact that there is so little suspense for the reader, however, does not mean that on the story level, within the saga, the characters are constrained by fate. At the sagas most crucial and powerful moments the author stresses the element of free choice: Gunnar chooses to stay in Iceland at the same moment that his brother Kolskegg decides to continue on his way abroad (Ch. 75); Njal is given free exit from the flaming Bergthorshvol, but makes a reasoned decision to remain inside (Im an old man and hardly fit to avenge my sons, and I do not want to live in shame), as does his wife (I was young when I was given to Njal, and I promised him that one fate should await us both, Ch. 129); his sons could stay outside where they have a good chance of repelling the attackers, but they go inside to their death because they choose to follow their fathers wishes (Ch. 128). Even the strict requirements of the feud pattern and honour code allow free choice, as Hall of Sida illustrates so nobly. LAW More than any other family saga, Njals Saga is about law. The first person mentioned though he initiates only one case and is a minor figure in the saga is described in terms of his ability at law. From Njals famous statements that with law our land shall rise, but it will perish with lawlessness (Ch. 70) and it will not do to be without law in the land (Ch. 97), to the swift conversion to Christianity by means of an arbitrated settlement at the Law Rock (Ch. 105), to the lengthy trial in Chs. 1414, the author shows a serious concern for law. This interest is also evident from his mastery of legal technicalities, whether he acquired it from lawbooks or from orally transmitted codes. The courtroom scenes in Chs. 73 and 1414 testify to a more than unusual delight in legal formulas and procedures, often to the readers dismay. In some cases he seems to have copied down (or remembered) legal phrases without adapting them to the context in the saga. When Mord brings charges against Flosi Thordarson for having assaulted Helgi Njalsson and inflicted on him an internal wound or brain wound or marrow wound which proved to be a fatal wound (Ch. 141), the author is slavishly repeating the entire textbook phrase, without eliminating the two kinds of wounds that do not apply in this case. Mords suit in Ch. 142 contains this statement: I declared all his property forfeit, half to me and half to the men in the quarter who have the legal right to his forfeited property. I gave notice of this to the Quarter Court in which this suit should be heard according to law Again, the formulation remains general, when it would have been proper to specify the East Quarter.Although the author earnestly endeavours to give the impression of the full and proper procedure around the year 1000, the legal details reflect his own time rather than that of the saga age. Laws were first written down in Iceland in 1117, and some of the phraseology in the saga corresponds word-for-word with passages in the Grgs (Grey-goose) legal texts, written down in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries not as an official lawbook, but as private copies of the law. Njla also has borrowings from a later code, the Jamsia (Iron-side), introduced from Norway in 1271. Njla is not only a law saga, it is an Althing saga. Many of the most important scenes in the saga, and not only legal scenes, take place at the annual general assembly at Thingvellir. In the text, and in the translation, the simple form Thing often appears, but we can assume, unless informed otherwise, that the reference is to the Althing at Thingvellir rather than to one of the local assemblies.The Althing is often, but not always, the place where a feud could be regulated. The three ways in which this might be done are neatly summed up in a dialogue between Hildigunn and Flosi in the famous whetting scene in Ch. 116: What action can I expect from you for the slaying, and what support? she asked. Flosi said, I will prosecute the case to the full extent of the law, or else make a settlement that good men see as bringing honour to us in every way.She spoke: Hoskuld would have taken vengeance if it were his duty to take action for you.A legal case settled by the courts, arbitration (whether by a third party or directly between the two principals), or blood vengeance these are the three possibilities. In Njals Saga there are many feuds and many killings, and a number of cases are brought to the Althing for trial, but not one legal case is ever concluded. Even though the percentage of adjudicated cases is low in the sagas in general, and even though arbitration and vengeance were socially acceptable elements of feud, one would hope that court trials would have a higher score than zero in a saga so obsessed with law.That no conflict is settled in court in Njla is part of a larger irony, and no doubt a deliberate irony, since it is so obvious in the saga: law, even the elaborate law code of medieval Iceland, is incapable of controlling violence. As the saga progresses, there is increasing emphasis on blood vengeance, and after the burning at Bergthorshvol Kari refuses to consider any other form of settlement.The third alternative, arbitration, is used with some effect in Njla , especially in the early part. The killings of Hallgerds first two husbands are both settled peaceably by her father Hoskuld and her uncle Hrut, so satisfactorily that the offended parties (Osvif and Thorarin) are both said to be out of the saga (end of Chs. 12 and 17). It is a relief to see a character leave the saga with dignity and the assurance that no more trouble will come from him. Unfortunately this will not be the case in the remainder of the saga. There will be many arbitrated settlements (especially at Njals suggestion) and many acts of blood vengeance, but none of them will put an end to violence. Even with the six reciprocal killings initiated by their wives, escalating dangerously but nonetheless settled amicably between Njal and Gunnar (Chs. 3545), there is a false sense of security. For the fifth killing in this series, of Thord Freed-mans son by Sigmund and Skjold, Njal makes a settlement with Gunnar and asks Skarphedin to keep it. Skarphedin agrees but if anything comes up between us, we shall have this old hostility in mind (Ch. 43).Old hostilities, lying under the surface but waiting to erupt in bloodshed, constitute the underlying narrative thread. The principal one goes straight from the slaying of Thord Freed-mans son (Ch. 42), to that of Thrain Sigfusson (Ch. 92), to that of Hoskuld Thrainsson (Ch. in), to the burning at Bergthorshvol (Chs. 12930). The direct links between these four acts, though sometimes overlooked by the reader, explain much of what is going on and illustrate the volatile nature of feud. When the Njalssons set out to kill Thrain in Ch. 92 they have a verbal exchange with their father that echoes the one they had in Ch. 44, when they set out to avenge Thord. After this conversation, when Kari asks Skarphedin why he killed Sigmund the White, Skarphedins answer is straightforward: He had killed Thord Freed-mans son, my foster-father. The killing of Thord at which Thrain was a consenting presence has led to the need to kill Thrain now (though Thrain has since given the Njalssons additional reason to kill him). The old hostility between the Njalssons and the Sigfussons, of whom Thrain was the most prominent, had been there all the time.The slaying of Hoskuld Thrainsson is the next inevitable link in this chain, but it is not easy for the reader to comprehend the slaying of this innocent, non-violent man, Njals beloved foster-son, especially since the killers are Njals own sons. The overt reason is the slander spread by Mord Valgardsson, at the prompting of his father. If this were the only reason, the Njalssons would appear very gullible and foolish, but there are two underlying motivations. One has to do with power (and perhaps a touch of jealousy). Njal did not trouble to find a godord for Skarphedin, his oldest son, or even a prominent marriage. The much younger Hoskuld, on the other hand, is well married and on the way to becoming a powerful godi, as Valgard noticed. That might be tolerable in itself, but there is the additional fact that Hoskuld is the son of Thrain Sigfusson. Old hostilities do not die. (One might even question the wisdom of Njals fostering the son of his own sons bitter enemy.) The other motivation for the killing has to do with the rules of feud. Lytings killing of Hoskuld Njalsson (Ch. 98) required vengeance by the Njalssons, and when Lyting is killed by Amundi in Ch. 106, the Njalssons direct their vengeance quite properly at the most prominent member of the offending family, who happens to be Hoskuld Thrainsson, their own foster-brother. It is a tragic clash of loyalties, and the Njalssons follow the course they think they must.The two greatest crises in the saga, the death of Gunnar and the burning at Bergthorshvol, both occur when an arbitrated agreement has been broken. It was agreed that Gunnar should go abroad for three years after killing Thorgeir Otkelsson. When he breaks the agreement and decides to remain at home (Ch. 75) he invites the attack which will cause his death, as Njal has warned him. Later, the settlement which good men have carefully arbitrated for the slaying of Hoskuld is nullified by the unforgivable insults exchanged by Flosi and Skarphedin (Ch. 123).The final legal scene in the saga (Chs. 1414) is the longest, dramatizing finally and fully both the intricate complexity of the law and the futility of the law, even in face of the fact that the burning at Bergthorshvol was an unjustifiable act. After the lengthy formulaic presentation of the suit against the burners, Eyjolf Bolverksson (Flosis lawyer) makes a number of attempts, using the fine points of the law, to quash the case. Thorhall Asgrimsson is able to meet each objection and save the case. It is a fine battle between the best lawyers in the land, told from the point of view of the spectators and creating the excitement of a good tennis game in which the advantage alternates between the two sides: Everyone. agreed that the defence was stronger than the prosecution they agreed that the prosecution was stronger than the defence. Finally Eyjolf serves his final ace (end of Ch. 144), to which there is no answer. In a proper court this would have been the end of the procedure, but in Njals Saga it is the occasion for violence. No scene better illustrates the failure of law and the failure of the Althing than when the lawyer Thorhall thrusts his spear into his infected leg, hobbles to the Fifth Court and kills the first kinsman of Flosis that he meets, thus initiating the total disorder of the battle at the Althing (Ch. 145). With law our land shall rise, but it will perish with lawlessness. CHRISTIAN AND PAGAN The pagan Germanic ethic of honour, courage and the blood feud is well illustrated in Njla . Men fight and die to enhance or at least preserve their good name. Hrut and Gunnar and Skarphedin and Kari and Flosi are noble men in the old mould, moved by a keen sense of personal honour. The saga has a pleasing abundance of epic situations fights against overwhelming odds, heroes who set out on a journey despite warnings of danger, men caught in a difficult position because of divided allegiances. The narrative derives much of its impetus and interrelatedness from the rules of feud and the requirements of honour.But there is another, softer strain in the saga. Njal, the central figure, never lifts a weapon, and he gains respect because of his jurisprudence, his prophetic wisdom and his good will. Gunnar, in many ways the perfect Germanic hero, fights (in Iceland at any rate) only when provoked to do so, and with great reluctance. Hoskuld Thrainsson never lifts a weapon, not even the one he is carrying on that fateful day when he is slain in his own field. Snorri the Godi is one of the most respected men in the land, but when Skarphedin taunts him for not having avenged his father, his answer is that of a mild man: Many have said that already, and Im not angered by such words (Ch. 119).The person in the saga who illustrates this strain most steadily is Hall of Sida. His first action in the saga is to accept Christianity for himself and his household (Ch. 100). Repeatedly his voice is the voice of peace and conciliation: as spokesman for the Christian side, it is he who at great risk asks the pagan Thorgeir to decide which faith should prevail in Iceland (Ch. 105); after Flosi has been whetted to blood vengeance by Hildigunn, Hall tries to persuade him to make a peaceful settlement (Ch. 119); when the trial for the slaying of Hoskuld is thwarted, Hall persuades Flosi to accept arbitration (Ch. 122); when Flosi, after the burning, has paid an insulting visit to Asgrim, Hall tells him frankly that he went too far (Ch. 136); when Thorgeir and Kari have started on their course of revenge for the burning, it is Hall who performs the diplomatic task of persuading Flosi and Thorgeir to be reconciled (Chs. 1467). Most impressive of all are his determined action to end the battle of the Althing, in which his son Ljot has been killed, and his plea to both sides to make a settlement: Hard things have happened here, both in loss of life and in lawsuits. Ill show now that Im a man of no importance. I want to ask Asgrim and the other men who are behind these suits to grant us an even-handed settlement Shortly after, in order to facilitate the settlement, he adds: All men know what sorrow the death of my son Ljot has brought me. Many will expect that payment for his life will be higher than for the others who have died here. But for the sake of a settlement Im willing to let my son lie without compensation and, whats more, offer both pledges and peace to my adversaries. (Ch. 145) When we read that one of the leading godis in Iceland calls himself a man of no importance and renounces any form of redress for his dead son, we are witnessing the complete antithesis of the old code of honour, in fact a new kind of honour.The two strains are neatly counterpointed in the feud between Hallgerd and Bergthora in Chs. 3545. On the one hand the two women act systematically according to the code of feud, each killing giving the occasion for the next. On the other hand their husbands, who would normally carry out blood revenge, make generous offers of peace on each occasion.How do these two strains relate to the Christian element in the saga? This element is especially strong during and after the account of the Conversion in Chs. 100105, although as early as Ch. 81 Kolskegg (Gunnars brother) is baptized in Denmark and becomes a Christian knight. Religious terms like baptism, preliminary baptism, Mass, the angel Michael, responsibility before God and God is merciful begin to appear after Ch. 100, and at least three memorable utterances catch the ear with their religious overtones: Hoskulds dying words May God help me and forgive you (Ch. 111); Njals plangent cry over that same killing, when I heard that he had been slain I felt that the sweetest light of my eyes had been put out (Ch. 122); and Njals words of comfort at the burning, Have faith that God is merciful, and that he will not let us burn both in this world and in the next (Ch. 129). The battle of Clontarf in the final chapters is pointedly fought between pagan and Christian forces, and the Christian side wins.At times the two sets of values, Christian and pagan, intersect in a way that seems strange today. When Hildigunn goads Flosi by throwing Hoskulds blood-stained cloak over his shoulders, her words combine Christian imprecation with an appeal to Flosis sense of honour: In the name of God and all good men I charge you, by all the powers of your Christ and by your courage and manliness, to avenge all the wounds which he received in dying or else be an object of contempt to all men (Ch. 116). A few lines after Njal spoke the words of Christian comfort quoted above, he declines an offer of free exit from the burning house with these words: I will not leave, for Im an old man and hardly fit to avenge my sons, and I do not want to live in shame. It may be that in such conflations of Christian language and the code of honour we see best how Christianity functions in this saga not as antithetical to pagan values but as complementary. Christianity did not at first condemn the blood feud, and the noblest pagan virtues were consonant with Christian values.There is a clear Christian presence in the saga, but the question is, does it change anything? It has become common to regard the Conversion episode in Chapters 100105 as marking a turning-point in the moral structure of the saga, whereby the older, pagan ethic of heroism and pride is replaced by a new Christian ethic of mildness and peace. Such a view is based on a false opposition between pagan and Christian; it overlooks the fact that there are other pagan virtues than heroism and pride, and that humility and a willingness to make peace are among them. Christianity does not affect the values already existing in the saga, in Gunnars and Njals moderation and love of peace, or in the young Hoskulds willingness to be content with the compensation paid for his father (Ch. 94). Those values were there before the Conversion, and continue after it, though set in a changed historical context. A Christian reading would have to judge Flosis burning of Bergthorshvol as a sin in the light of the martyrs death suffered by Njal. The saga, however, treats the burning as a necessary but regrettable deed, and Flosi emerges from it with honour. Nor does the coming of Christianity have any direct effect on the course of events. The Christian elements in the saga are part of its historical realism, of its rhetoric. After the Conversion in the year 1000 people are made to think and speak in religious terms, and there is a new spirit in the land, but the events of the saga follow their own course, quite unaffected by it.The claim has also been made that it is their pilgrimages to Rome and the absolution they received there that enable Kari and Flosi to become reconciled at the end of the saga. The reconciliation comes after the pilgrimages, to be sure, but it does not come because of them. The reconciliation results from full and sufficient blood revenge, sheer exhaustion and the mutual respect these two good men have long had for each other. The feud, the longest and deadliest in any of the sagas, has simply run its course. What Kari demonstrates is not the value of Christian absolution, but that the only way to end a feud for once and for all is to carry out total vengeance.The thirteenth-century author of Njals Saga was a Christian, looking back with respect at his pagan forebears and the time when Christianity came to his country. He is not preaching a sermon, nor writing a theological treatise, for he knows that the two systems are in many ways compatible. His characters may convert, and acquire Christian rhetoric, but they do not change their nature. Njal is the same man after the Conversion as before, and Hall and Hoskuld would have been the same as they are had there been no Conversion. Njals Saga is secular literature. THE TWO PARTS Finally, a consideration of parallels and contrasts between the two main parts of the saga, Gunnars story and Njals story, may help to clarify the shape of the saga. In both sections a series of events growing out of feuds lead to the heros being attacked and killed at his own home, after which revenge is exacted. The attack comes when a settlement for a major offence committed by the heros side is broken or rejected, leaving the way open for his enemies to attack in force. In both stories Mord Valgardsson plots to bring about the heros downfall, which comes after two killings (of father and son) in the same family. The contrasts between the two sections are instructive: burning the besieged in his house, which was rejected as shameful in the attack on Gunnar, is the tactic used in the attack on Bergthorshvol, and Hallgerds betrayal is counterpoised by Bergthoras willingness to die with her husband. The chief contrasts between the Gunnar story and the Njal story, however, are in the nature of the narrative line and in dimension. Gunnar becomes entangled in a series of clashes with different opponents Otkel and his allies, Starkad and Egil and their sons who eventually join together to form an overwhelming force against him. In Njals story there is a single, straight plot line, from the slaying of Thrain Sigfusson (and even before) to the burning. The other main contrast is the greatly increased scale, which creates, in addition to the rhythm of hopes raised and dashed, a sense of ever heavier seriousness. It may seem callous to speak of Gunnars feuds as trivial, since enmities are aroused and men are killed, but in comparison to the immense gravity of the feud in the second part they come off as petty stuff. The killing of the promising Thorgeir Otkelsson is regrettable; the killing of the saintly Hoskuld Thrainsson is tragic. Forty men attack Hlidarendi; a hundred (meaning a hundred and twenty in the old sense of hundred) attack Bergthorshvol. After his death Gunnar sings in his mound like a bold pagan. The pathos of the deaths of Hoskuld and of Njal and his family, heightened by Christian overtones, is unmatched by anything in the first part of the saga. The vengeance for Gunnar occupies one chapter and falls on four men; for Njal it occupies twenty-seven chapters and some thirty men die. Gunnars chief enemies were shallow men, though they dragged some prominent figures along with them. Njals chief enemies include, with good reason, some of the best men in Iceland. Njals Saga is a large and ponderous saga, and especially the second half shows how massive the effects of human folly and how ineffective human intelligence can be. POSTSCRIPT This introduction has been drafted in a rented cottage at Brekkuskgur in Biskupstunga in the south-west of Iceland, just short of the rim of the uninhabited central highland, about ten kilometres from the hot springs at Geysir. Two kilometres north of Geysir is Haukadal, where Thangbrand baptized Hall Thorarinsson (see Ch. 102), and where Ari Thorgilsson (author of The Book of Icelanders ) spent his formative years in the late eleventh century. Two or three kilometres from where I sit, up the road towards Geysir, is the still-working farm Hlid (now called Uthlid), to which Geir the Godi retired when he left our saga in Ch. 80.Looking south-east from my veranda I see the steam rising from Reykir (the name means steams) five kilometres away, just as it rose a thousand years ago when the forces of Thorgeir Skorargeir and Mord Valgardsson met with Asgrim Ellida-Grimsson to ride together to the momentous Althing (Ch. 137). In that chapter it is reported that they first crossed the Bruara (Bridge river), and indeed the river at that point (width 25 metres, current swift) shows me that this was a detail worth mentioning, just as the impressive columns of steam would have made Reykir a natural meeting place. Looking beyond Reykir, twelve kilometres further on from where I sit rises the mountain of Mosfell, which gave its name to the farm at its southern foot where Gizur the White lived. And although an intervening rise prevents me from seeing it, I know that four kilometres south of Mosfell is Tunga, Asgrim Ellida-Grimssons farm on the river Hvita. With such abundant, palpable evidence to hand it is not surprising that generations of Icelanders regarded the sagas as literally true. Is there any literature as firmly anchored to geographical reality, not to mention socio-historic reality, as the Icelandic sagas?Fortunately, enjoying this saga to the full does not require having Icelandic blood or having trod the saga sites. In fact it can be misleading to know the sites, and an advantage not to know them. The alert reader will have noticed how, in my musings in the previous paragraph, I was beginning to think that Asgrim and Thorgeir really met at Reykir with their combined forces, and that Geir the Godi though we can be fairly certain he lived at Hlid in fact did the things the saga says he did. The reader should not be seduced by the dry, factual prose style and the convincing social and geographical setting into thinking that this is anything other than a masterful work of prose fiction. Further Reading Translations into English The Story of Burnt Njal , translated by George Webbe Dasent (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1861); reprinted in Everymans Library, 1911; reissued in 1957 with an introduction by E. O. G. Turville-Petre. Njls Saga , translated by Carl F. Bayerschmidt and Lee M. Hollander (New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1955); this translation has been reprinted, with an introduction by Thorsteinn Gylfason, by Wordsworth Editions Limited (1998). Njals Saga , translated by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Plsson (Harmondsworth: Penguin, i960). Njals Saga , translated by Robert Cook, in Viar Hreinsson et al . (eds.) The Complete Sagas of Icelanders ( Including 49 Tales ), 5 volumes (Reykjavk; Leifur Eirksson, 1997), III, 1220; an earlier version of the present translation. Other Primary Sources in Translation Ari Thorgilsson, The Book of the Icelanders , translated in Gwyn Jones, The Norse Atlantic Saga , second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 14355. The Book of Settlements; some passages in the above; a translation of one version by Hermann Plsson and Paul Edwards (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1972). Laws of Early Iceland. Grgs I-II , translated by Andrew Dennis, Peter Foote and Richard Perkins (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1980 and 2000). The Sagas of Icelanders , with an introduction by Robert Kellogg, includes the following: Egils Saga; The saga of the People of Vatnsdal; The Saga of the People of Laxardal; The Saga of Hrafnkel Freys Godi; The Saga of the Confederates; Gisli Surssons Saga; The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue; The Saga of Ref the Sly; The Vinland Sagas, (the Saga of the Greenlanders and Eirik the Reds Saga); and seven Tales (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 2000). General Criticism of the Sagas of Icelanders Andersson, Theodore M., The Problem of Icelandic Saga Origins (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964).The Textual Evidence for an Oral Family Saga, Arkiv for nordisk filologi , 81 (1966), 123., The Displacement of the Heroic Ideal in the Family Sagas, Speculum , 45 (1970), 57593.Kellogg, Robert, and Scholes, Robert, The Nature of Narrative (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966).Ker, W. P, Epic and Romance (London: Macmillan, 1897).Miller, William Ian, Bloodtaking and Peacemaking: Feud, Law, and Society in Saga Iceland (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).Nordal, Sigurdur, The Historical Element in the Icelandic Family Sagas, W P. Ker Memorial Lectures, 15 (Glasgow, 1957).lason, Vsteinn, Dialogues with the Viking Age: Narration and Represen tation in the Sagas of the Icelanders , translated by Andrew Wawn (Reykjavk: Ml og menning, 1998).Schach, Paul, Icelandic Sagas (Boston: Twayne, 1984). Studies of Njals Saga Allen, Richard F, Fire and Iron: Critical Approaches to Njls saga (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1971).Clover, Carol J., Hildigunnrs Lament, in John Lindow, Lars Ldie;nnroth and Gerd Wolfgang Weber (eds.), Structure and Meaning in Old Norse Literature (Odense: Odense University Press, 1986), 14183.Dronke, Ursula, The Role of Sexual Themes in Njls Saga , Dorothea Coke Memorial Lecture, University College London (London: Viking Society, 1981).Fox, Denton, Njls Saga and the Western Literary Tradition, Comparative Literature , 15 (1963), 289310.Jesch, Judith, Good Men and Peace in Njls saga , in John Hines and Desmond Slay (eds.), Introductory Essays on Egils saga and Njls saga (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1992), 6482.Lnnroth, Lars, Njls Saga: A Critical Introduction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976).Maxwell, Ian, Pattern in Njls saga, Saga-Book , 15 (195761), 1747.Miller, William Ian, Justifying Skarpheinn: Of Pretext and Politics in the Icelandic Bloodfeud, Scandinavian Studies , 55 (1983), 31644.Poole, Russell, Darraarlj: A Viking Victory over the Irish, in his Viking Poems on War and Peace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 11656.Sayers, William, Gunnar, his Irish Wolfhound Smr, and the Passing of the Old Heroic Order in Njls saga, Arkiv f r nordisk filologi , 112 (1997), 4366.Sveinsson, Einar lafur, Njls Saga: A Literary Masterpiece , edited and translated by Paul Schach (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971). A Note on the Translation This translation is based on the edition of Brennu-Njls saga by Einar lafur Sveinsson, slenzk Fornrit, 12 (Reykjavk, 1954). It differs from previous translations of Njls Saga , except for Dasents in 1861, in attempting to duplicate the sentence structure and spare vocabulary of the Icelandic text. Subordinate clauses, introduced by conjunctions like when, because, who, although and so on, are relatively infrequent in the saga (indeed in all the Icelandic sagas), where there is a marked preference for independent clauses. The saga typically says: They had a short passage and the winds were good (Ch. 9), not They had a short passage because the winds were good. Often an independent clause stands alone, but at other times a group of independent clauses is joined by a series of ands and buts, producing a sentence like this: Glum often raised this matter with Thorarin, and for a long time Thorarin avoided it, but finally they gathered men and rode off, twenty in all, westward to Dalir and they came to Hoskuldsstadir, and Hoskuld welcomed them and they stayed there overnight (Ch. 13). This is an effective way of hastening the narrative when the author wants to cover a sequence of events quickly.Another feature imitated in this translation is the absence of the present participle, a standard fixture in modern English and therefore natural in a passage like this (Ch. 145) from the translation by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Plsson: Kari Solmundarson met Bjarni Brodd-Helgason. Kari seized a spear and lunged at him, striking his shield; and had Bjarni not wrenched the shield to one side, the spear would have gone right through him. He struck back at Kari, aiming at the leg; Kari jerked his leg away and spun on his heel, making Bjarni miss. [italics added] Here, by contrast, is the same passage as translated in this volume, in greater conformity with the original: Kari Solmundarson came up to Bjarni Brodd-Helgason; he grabbed a spear and thrust it at him, and it hit his shield. Bjarni jerked his shield to the side otherwise the spear would have gone through him. He swung his sword at Kari and aimed at the leg; Kari pulled his leg back and turned on his heel, so that Bjarni missed him. This translation also tries to reproduce the limited vocabulary of the Icelandic text. In describing travel, for example, there is seldom much variation beyond go and walk and ride. Direct speech (which, by the way, constitutes about forty per cent of this saga) is introduced by say or speak or ask or answer. This translation keeps to the principle of minimal variation and introduces no artificial additives like declare (except in legal scenes), emphasize, assert, respond, retort, reply, question and inquire. The verb say is often used with questions as well as with statements, and the result may seem to be an over-use of that verb, as in the following: Njal said , I must tell you of the slaying of your foster-father Thord; Gunnar and I have just made a settlement on it, and he has paid double compensation. Who killed him? said Skarphedin. Sigmund and Skjold, but Thrain was close at hand, said Njal They thought they needed a lot of help, said Skarphedin. But how far must this go before we can raise our hands? Not far, said Njal, and then nothing will stop you, but now its important to me that you do not break this settlement. (Ch. 43) It is hoped that the reader of this translation will accept and even learn to enjoy these and other efforts at fidelity, though they may seem strange at first. The intent has been to create a translation with the stylistic feel of the Icelandic original.As is common in translations from Old Icelandic, the spelling of proper nouns has been simplified, both by the elimination of non-English letters and markings and by the reduction of inflections. Thus Hallgerr becomes Hallgerd, Hskuldr becomes Hoskuld, and Smr (pronounced, roughly, Sowmer) turns dully into Sam. Characters are frequently identified in terms of their fathers, and readers will soon grasp that -dottir means daughter of and that -son means son of . Place names have been rendered a trifle more conservatively than is usual, Laxardalr becoming Laxrdal rather than Lax River Valley. Chronology of Njals Saga The following table of some of the main events of the saga and of early Icelandic history is based on the research of Gudbrandur Vigfsson and Finnur Jnsson, as reviewed by Einar lafur Sveinsson in his 1954 edition of the saga. The dates are of course approximate, even for the events that actually took place (indicated in bold face). Of course, most events in the saga are fictional, and the dates estimated here are meant only to give an overview of the time span and sequence of events. It should be mentioned that the Establishment of the Fifth Court is out of historical sequence in the saga; the general view is that it took place in 1004.Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Njal’s Saga»

Look at similar books to Njal’s Saga. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Njal’s Saga and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.