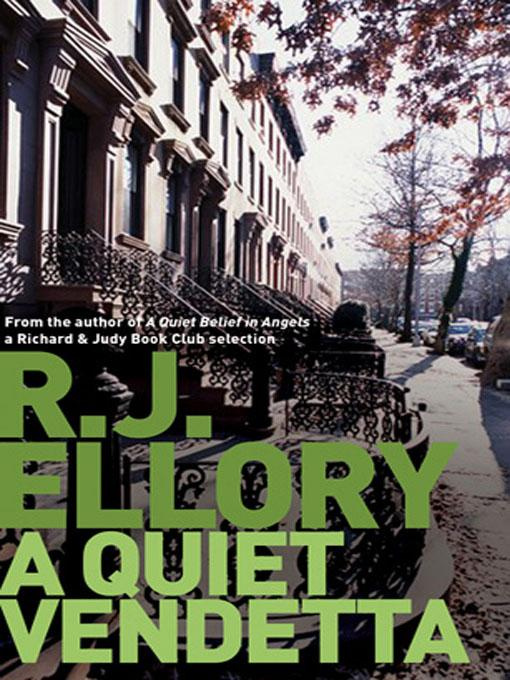

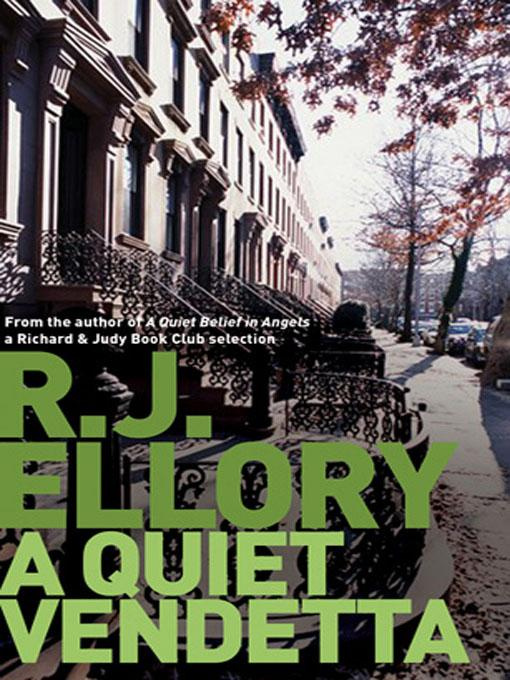

R. J. Ellory

A Quiet Vendetta

Copyright R. J. Ellory Publications Ltd 2005

To all those at Orion: Malcolm Edwards, Peter Roche, Jane Wood, Gaby Young, Juliet Ewers, Helen Richardson, Dallas Manderson, Debbie Holmes, Kelly Falconer, Kate Mills, Sara OKeeffe, Genevieve Pegg, Susan Lamb, Susan Howe, Jo Carpenter, Andrew Taylor, Ian Diment, Mark Streatfeild, Michael Goff, Anthony Keates, Mark Stay, Jenny Page, Katherine West and Frances Wollen. As well to Mark Rusher at Weidenfeld & Nicolson; and to Robyn Karney, my own Thelma Schoonmaker the embodiment of patience and care.

To Jon Wood, editor and consigliere.

To my agent and friend, Euan Thorneycroft.

To Ali Karim at Shots Magazine and Steve Warne at CHC Books.

To Dave Griffiths at Creative Rights Digital Registry; the crew of BBC Radio WM; Maris Ross at Publishing News; The UK Crime Writers Association; Daniel, David and Thallia at Goldsboro Books; Richard Reynolds at Heffers in Cambridge and Paul Blezard at One Word Radio.

To Sgt Steve Miller, Metro-Dade Crime Laboratory Bureau, Miami, FLA, for staying after-hours to answer questions about body parts and the frailty of human beings.

To my brother, Guy.

To my wife of sixteen years, my son of eight.

I owe you all.

This is a work of fiction.

Irrespective of the fact that it is set against historical events and amidst people whose names you will recognize, it is nevertheless a work of fiction. Where actual events have been modified, or perhaps a sequence changed, this was done only to facilitate the telling of the story.

Many of the people herein are long-since dead, and perhaps the world is a better place for it, but they populated my life for some weeks, and in their own way gave generously of themselves. Some of them were funny, some of them disturbing, others just downright crazy. Regardless they came and went, they made their mark, and I acknowledge them for their contribution.

It has been said that the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts, and perhaps in collating and binding these parts together I have made errors. For this I assume complete responsibility, but also plead an element of mitigating circumstance: I was in bad company at the time.

The Author

Approaching death,

as we think, the death of love,

no distinction,

any more suffices to differentiate

the particulars

of place and condition

with which we have been long

familiar.

All appears

as if seen

wavering through water.

From Asphodel, That Greeny Flower, Book II

William Carlos Williams

Through mean streets, through smoky alleyways where the pungent smell of raw liquor hangs like the ghost of some long-gone summer; on past these battered frontages where plaster chips and twists of dirty paint in Mardi Gras colors lean out like broken teeth and fall leaves; passing the dregs of humanity who gather here and there amongst brown-papered bottles and steel-drum fires, serving to tap the vein of meager human prosperity where it spills, through good humor or diesel wine, onto the sidewalks of this district

Chalmette, here within the boundaries of New Orleans.

The sound of this place: the jangled switching of interference, the hurried voices, the lilting piano, the radios, the street-walking, hip-dipping youths playing mesmeric rap.

If you listen, you can hear from porch or stoop the quarreling voices, innocence already bruised, challenged, insulted.

The clustered tenements and apartment blocks, pressed between streets and sidewalks like some secondary consideration, the unwanted reprise of an earlier discarded theme, and running like a strung-together, slipshod archipelago, hopping a block at a time out through Arabi, over the Chef Menteur Highway to Lake Pontchartrain where people seem to stop merely because the earth does.

Visitors perhaps wonder what makes this ripe, malodorous blend of smells and sounds and human rhythms as they pass over the Lake Borgne canal, over the Vieux Carre business district, over Ursulines and Tortoricis Italian to Gravier Street. For here the sound of voices is strong, rich, vibrant, and there is motion spilling randomly, a pocket of curiosity gathered along the edge of a one-way street, a corridor of downward-sloping entries into parking lots beneath a tenement.

But for the squad car flashes, the alleyway is hot and thick with darkness. The tail-ends of cars chrome fenders and liquid silk paintwork catch the kaleidoscope flickers, and wide eyes flash cherry red to sapphire blue as police cars drive a wedge across the street and halt all passage.

To the left and right are hospitals, the Veterans and LSU Medical Center, and up ahead the South Claiborne Avenue Overpass, but here there is a splinter of activity through the network of arteries and veins that ordinarily flows uninhibited, and what is happening is unknown.

Patrolmen back the sensation-seekers away, herding them behind a hastily erected barrier, and once an arc lamp is hooked to the roof of a car, its beam wide enough to identify each and every vehicle pigeonholed in the alley, they begin to understand the source of this sudden police presence.

Somewhere a dog barks and, as if in echo, three or four more start up somewhere to the right. They holler in unison for reasons known only to themselves.

Third entrance from the Claiborne end a car is parked at an angle, its fender running a misplaced parallel to the others. Its positioning indicates speed, the rapid arrival and departure of its driver, or perhaps a driver who had not cared to harmonize with perspective and linear conformity, and though the carboy who walked this alleyway minding automobiles, polishing brights and hoods for a quarters tip has seen this car for three days consecutive, he hadnt called the police until hed looked inside. Hed taken a flashlight, a good one, and, pressing his face against the left rear quarterlight, hed scanned the luxurious interior, minding he didnt touch the white walls with his dirty, toe-peeping kickers. This wasnt no ordinary car. There was something about it that had drawn him inside.

More people had gathered by then, and down a half a block or so some folks had opened up the doors and windows on a house party and the music was coming down with the smell of fried chicken and baked pecans, and when a plain Buick showed up and someone from the Medical Examiners office stepped out and walked towards the alleyway there were quite a few people down there: maybe twenty-five, maybe thirty.

And there was music our human syncopations as good tonight as any other.

The smell of chicken reminded the MEs man of some place, some time he couldnt remember now, and then it started raining in that lazy, tail-end-of-summer way that seemed to wet nothing down, the kind of way no-one had a mind to complain about.

Itd been a hot summer, a quiet kind of brutality, and everyone could remember how bad the smell got when the storm drains backed up in the last week of July, and how they spilled God-only-knew-what out into the gutters. It steamed, the flies came, and the kids got sick when they played down there. Heat blistered at ninety, tortured through ninety-five, and when a hundred sucked the air from parched lungs they called it a nightmare and stayed home from work to shower, to wrap split ice in a wet towel and lie on the floor with their cool hats pulled down over their eyes.

The Examiner man walked down. Early forties, name was Jim Emerson; he liked to collect baseball cards and watch Marx Brothers movies, but the rest of the time he crouched near dead bodies and tried to put two and two together. He looked as lazy as the rain, and you could sense in the way he moved that he knew he was unwelcome. He knew nothing about cars, but theyd run a sheet through come morning and theyd find just like the carboy had figured that this wasnt no ordinary automobile.

Next page