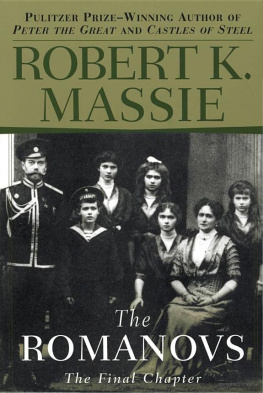

FASCINATING READING.

Detroit News

A narrative as gripping as a well-wrought murder mystery, told in vividly realized, densely atmospheric scenes, rich with moments of grim fascination.

The Washington Post Book World

Massie examines the extraordinary fate that has befallen the familys bones and explores what science now reveals about the woman who claimed to be Anastasia, the tsars youngest daughter.

USA Today

The Romanovs has the page-turning pace of a good detective story combined with impeccable historical scholarship.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

A meticulously researched, tragicomic tale of greed, intrigue, and genuine truth-seeking Massie should have given lessons to O. J. Simpsons prosecutors on how to make science intelligible to the average citizen.

Newsday

Excellent In a thorough and fair-minded job of reporting, [Massie] narrates the post-Ekaterinburg history of the Romanovs, from the executioners shots to the identification of the remains through DNA analysis [and] lucidly explains the complex scientific, dynastic, and political issues.

Detroit Free Press

One part horror, two parts mystery, and the whole thing history, The Romanovs is the ultimate thriller.

Milwaukee Journal

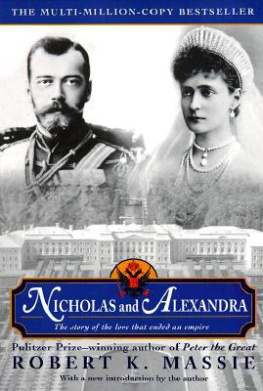

Best known for his epic Nicholas and Alexandra, Robert K. Massie proves himself equally skillful as shoeleather historian in The Romanovs. He engagingly amplifies a story that is, for all its elements of pageantry and high drama, also quite simple and earthily human.

BookPage

Almost as much thriller as historical account With memorable sketches of the main participants and a skillful discussion of the scientific evidence, Massie pulls together a sprawling theme and infuses it with quiet drama.

Kirkus Reviews

A Ballantine Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

Copyright 1995 by Robert K. Massie

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

A portion of this work was originally published in the August 21/28, 1995, issue of The New Yorker.

Excerpt from The Murder of the Romanovs, by Captain Paul Bulygin, published in 1935 by Hutchinson, a division of Random House UK, London.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Doubleday, a division of the Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.: Excerpts from The Last Tsar, by Edvard Radzinsky (Doubleday, 1992). Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, a division of the Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Yale University Press: Excerpts from the diary of Empress Alexandra are from The Last Diary of Empress Alexandra, 1918, edited by Carl Emerson and VA. Kozlov, to be published by Yale University Press in Fall 1996. Reprinted by permission.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.ballantinebooks.com

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-96533

eISBN: 978-0-307-87386-6

This edition published by arrangement with Random House, Inc.

v3.1

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

DOWN TWENTY-THREE STEPS

At midnight, Yakov Yurovsky, the leader of the executioners, came up the stairs to awaken the family. In his pocket he had a Colt pistol with a cartridge clip containing seven bullets, and under his coat he carried a long-muzzled Mauser pistol with a wooden gun stock and a clip of ten bullets. A knock on the prisoners door brought Dr. Eugene Botkin, the family physician, who had remained with the Romanovs for sixteen months of detention and imprisonment. Botkin was already awake; he had been writing what turned out to be a last letter to his own family.

Quietly, Yurovsky explained his intrusion. Because of unrest in the town, it has become necessary to move the family downstairs, he said. It would be dangerous to be in the upper rooms if there was shooting in the streets. Botkin understood; an anti-Bolshevik White Army bolstered by thousands of Czech former prisoners of war was approaching the Siberian town of Ekaterinburg, where the family had been held for seventy-eight days. Already, the captives had heard the rumble of artillery in the distance and the sound of revolver shots fired nearby on recent nights. Yurovsky asked that the family dress as soon as possible. Botkin went to awaken them.

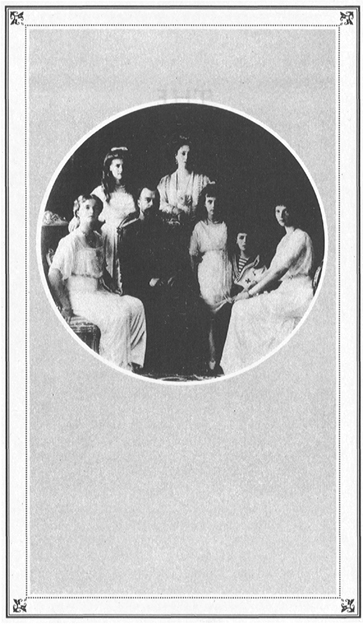

They took forty minutes. Nicholas, fifty, the former emperor, and his thirteen-year-old son, Alexis, the former tsarevich and heir to the throne, dressed in simple military shirts, trousers, boots, and forage caps. Alexandra, forty-six, the former empress, and her daughters, Olga, twenty-two, Tatiana, twenty-one, Marie, nineteen, and Anastasia, seventeen, put on dresses without hats or outer wraps. Yurovsky met them outside their door and led them down the staircase into an inner courtyard. Nicholas followed, carrying his son, who could not walk. Alexis, crippled by hemophilia, was a thin, muscular adolescent weighing eighty pounds, but the tsar managed without stumbling. A man of medium height, Nicholas had a powerful body, full chest, and strong arms. The empress, taller than her husband, came next, walking with difficulty because of the sciatica which had kept her lying on a palace chaise longue for many years and in bed or a wheelchair during their imprisonment. Behind came their daughters, two of them carrying small pillows. The youngest and smallest daughter, Anastasia, held her pet King Charles spaniel, Jemmy. After the daughters came Dr. Botkin and three others who had remained to share the familys imprisonment: Trupp, Nicholass valet; Demidova, Alexandras maid; and Kharitonov, the cook. Demidova also clutched a pillow; inside, sewed deep into the feathers, was a box containing a collection of jewels; Demidova was charged with never letting it out of her sight.

Yurovsky detected no signs of hesitation or suspicion; there were no tears, no sobs, no questions, he said later. From the bottom of the stairs, he led them across the courtyard to a small, semibasement room at the corner of the house. It was only eleven by thirteen feet and had a single window, barred by a heavy iron grille on the outer wall. All the furniture had been removed. Here, Yurovsky asked them to wait. Alexandra, seeing the room empty, immediately said, What? No chairs? May we not sit? Yurovsky, obliging, went out to order two chairs. One of his squad, dispatched on this mission, said to another, The heir needs a chair evidently he wants to die in a chair.