A Note on Names, Dates and Titles

Russians used the old-style Julian calendar until 1 February 1918. This was twelve days behind the West in the nineteenth century and thirteen days behind it in the twentieth century. Dates have been used according to the western Gregorian calendar, which Queen Victoria would have used, although occasionally both sets of dates have been inserted for clarity.

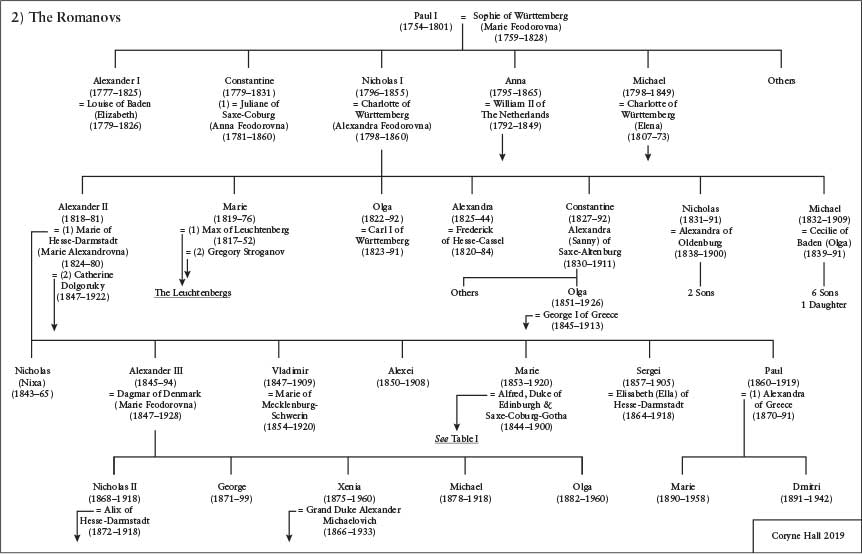

The titles emperor, empress, tsar and tsarina are all correct and are used interchangeably. The eldest son of the tsar was the tsarevich, other sons were grand dukes. Daughters were grand duchesses. The wife of the tsarevich was the tsarevna. From 1886 the title of grand duke/duchess was limited by Alexander III to the sovereigns children and grandchildren in the male line only; great-grandchildren of the sovereign were prince or princess.

Russians have three names their Christian name, patronymic (their fathers name) and their surname. The sons of Nicholas I and Nicholas II had the patronymic Nicolaievich; the daughters were Nicolaievna. The sons of Alexander II and Alexander III had the patronymic Alexandrovich; the daughters were Alexandrovna.

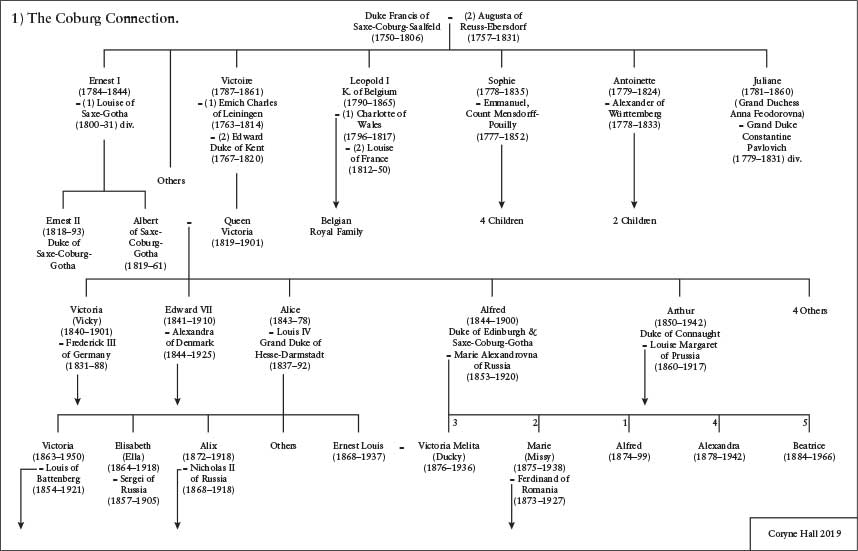

The members of the Romanov family dealt with in this book were all descended from Tsar Paul I, whose children had the patronymic Pavlovich or Pavlovna.

Apart from the senior branch (represented by the reigning tsar) there were three other main branches, who all descended from Nicholas Is sons: the Constantinovichi (descendants of Grand Duke Constantine Nicolaievich, 182792); the Nicolaievichi (descendants of Grand Duke Nicholas Nicolaievich, 183191); and the Michaelovichi (descendants of Grand Duke Michael Nicolaievich, 18321909). The Dukes of Leuchtenberg were descendants of Nicholas Is eldest daughter Grand Duchess Marie Nicolaievna (181976).

List of Illustrations

Princess Juliane of Saxe-Coburg as a young woman.

Princess Juliane of Saxe-Coburg (Grand Duchess Anna Feodorovna of Russia).

Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich.

King Leopold I of Belgium.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Tsarevich Alexander.

Tsar Nicholas I.

The Grand Review in Windsor Park, 1844.

Grand Duchess Marie Nicolaievna and her daughter Hlne Stroganov.

Queen Olga of Wrttemberg.

Grand Duke Constantine Nicolaievich.

Queen Olga of Greece.

Alexander II and Empress Marie Alexandrovna.

Princess Alice and Prince Louis of Hesse-Darmstadt.

Alexander II and his sons Alexander, Alexei and Vladimir.

The wedding of Prince Alfred and Grand Duchess Marie, 1874.

Alexander II with Alexei, Prince Alfred and Grand Duchess Marie.

The menu for the dinner at the Crystal Palace, 1874.

The children of the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh.

Victoria, Empress of India.

Queen Victoria with the Hesse family 1879.

Alexander III, Marie Feodorovna, the Princess of Wales and Grand Duchess Olga.

Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna (Ella) in court dress.

Grand Duke Sergei, Grand Duchess Ella, Grand Duke Paul and the latters children.

The future Nicholas II and his brother George, early 1870s.

Empress Marie Feodorovna with her younger children.

Alfred and Marie at a house party, 1894.

Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra driving to Balmoral, 1896.

Nicholas II and the Duke of Connaught, 1896.

Family group at Balmoral, 1896.

Grand Duchesses, Tatiana, Maria and Olga Nicolaievna.

Introduction

In November 2018 the exhibition Art, Russia and the Romanovs opened at the Queens Gallery, Buckingham Palace, emphasising the cultural links between the British and Russian royal families back to the reign of Peter the Great. Yet it is the reign of Queen Victoria that provides us with the most fascinating window into this complicated association.

Queen Victoria had an ambivalent relationship with Russia and its ruling family. Certainly her remarks about the Romanovs were not always complimentary. A sovereign whom she does not look upon as a gentleman

Selfish, demanding, obstinate and prone to bouts of self-pity the queen may have been but her ancestors had ruled (with one short break) for nearly a thousand years. Victoria considered the Romanovs, who had only been on the Russian throne since 1613, as upstarts, not to be compared with the British royal family and certainly not to the great German houses of Brunswick, Saxony and Hohenzollern. The Russians, she pronounced on another occasion, were wolves in sheeps clothing. In that respect Victoria would be proved right.

She did have some good words to say about Nicholas II once she got to know him, and she had a good rapport with Alexander II in their youth but the underlying suspicion and distrust was always there. As Victorias views on the Romanovs fluctuated, her empire and country would always come before family connections.

Her attitude is all the more significant as her godfather was Tsar Alexander I and she was christened Alexandrina in his honour, although they never seemed to have met. Queen Victoria was the daughter of Edward, Duke of Kent (the fourth son of King George III), and his wife Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. In 1814 after the abdication of Napoleon, Victoires brother Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld entered London with the Allied Sovereigns as a general in the tsars army. It was his friendship with Alexander I which allowed Leopold to meet and marry Princess Charlotte, only daughter of the Prince Regent (later George IV), heiress to the British throne, in 1816. By this time the Duke of Kent was deeply in debt but a marriage would ensure a settlement by parliament. Alexander I financed his trip to Germany to meet a prospective bride, the tsarinas sister Princess Katherine Amelia of Baden. Alas, she proved to be a forty-one-year-old spinster, so at the urging of Prince Leopold, Edward turned his attentions to the princes widowed sister Princess Victoire. She had previously been married to Prince Emich Charles of Leiningen, by whom she had two children, Charles and Feodora, and she saw no reason to marry a portly man twenty years her senior. She turned him down.

The death of Leopolds wife Charlotte (George IIIs only legitimate grandchild) in 1817 left the British monarchy in crisis. Prince Leopold urged his sister to reconsider. Any children she and Edward had would be close to the throne and Leopold saw a chance of regaining some of the power he had lost with Charlottes death. The widowed thirty-one-year-old Victoire married fifty-one-year-old Edward in 1818. The Times reported on 9 October that at a ball attended by the tsar at Aix-la-Chapelle, the Duchess of Kent attracted particular attention by the richness of her dress and the splendour of her jewels. Soon afterwards, Victoire realised she was pregnant.

As Edwards younger brothers raced to marry and provide an heir to the throne, the Duke of Kent won when Princess Alexandrina Victoria was born on 24 May 1819, at that time fifth in line to the throne. Her parents wanted to call her Georgiana after Edwards brother George the Prince Regent, but a message came from the Russian Embassy that the tsar wished to stand as sponsor (godfather). The Regent, who had fallen out with Alexander when the tsar visited London (and proved far more popular with the crowds) declared that his own name could not possibly follow that of the Russian emperor. So Alexandrina she became, with Victoria (after her mother Victoire) added as an afterthought after an argument between Edward and his brother at the font. Yet the tsars goddaughter remained resolutely anti-Russian all her life. This probably would not have mattered if she had not been destined to become queen but the deaths of both George III and her father Edward in 1820, followed by the childless Duke of York in 1827 and George IV in 1830 left only King William IV between Alexandrina Victoria and the crown.