Queen Victorias Daughters-in-Law

Queen Victorias Daughters-in-Law

John Van der Kiste

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright John Van der Kiste 2023

ISBN 978 1 39900 145 8

EPUB ISBN 978 1 39900 146 5

MOBI ISBN 978 1 39900 146 5

The right of John Van der Kiste to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: Uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

Iwould like to thank Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for permission to quote from correspondence in the Royal Archives, Windsor; Doa Beatriz de Orleans-Borbon y Parodi Delfino, for permission to quote from previously unpublished letters from the English translation of Ena and Bee: In defence of a royal friendship, by Ana de Sagrera; the Royal Archives, Madrid; Catherine Uecker, University of Chicago Library; and Karen Robson, Southampton University Archives, for access to and permission to quote material from their respective collections.

My particular gratitude goes to Sue Woolmans for her sterling work in undertaking research at the Royal Archives, Windsor (to say nothing of several very interesting discussions by email on the personalities of the four royal and imperial ladies who are the subject of this book), and Julie Crocker, Senior Archivist, and Colin Parrish, at the Archives, for their help in providing access to the correspondence; Ricardo Mateos Sinz de Medrano, for obtaining and sending me material from the Royal Archives and the John Wimbles Papers, Madrid; and to Coryne Hall, for her useful feedback and useful answers to various queries. I would also like to thank my editors at Pen & Sword, Claire Hopkins, Laura Hirst, Lori Jones, Amy Jordan, Lucy May, and Alan Murphy, for helping to see the work through to publication; Luvy Lubker, who originally suggested the subject as an idea for a forthcoming book; and my wife Kim, for her invaluable support during the three years that saw it gradually take shape.

Introduction

Queen Victoria had four sons and five daughters, and as a matriarch who always expected high standards of her children, she was equally demanding of those who married into the family. To be one of her daughters-in-law did not mean an easy life, and on occasion those who married into the family may have wondered what they had let themselves in for. All were women of determined character to a certain extent, although only the second one, born Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia, was known as the only member of the family whom the queen was unable to intimidate. They were likewise all sometimes exasperated by her efforts to control their lives, her constant interference in their private matters, her obstinacy and bursts of selfishness. Nevertheless, they all admired, liked, loved and respected her as a mother and sovereign, and appreciated that one has to be cruel to be kind.

In recent years, there has been a tendency towards revisionism in the biographies of some writers, and in television documentaries, to portray Queen Victoria in a harsher light as a selfish, ill-tempered, domineering control freak. It is always easy to be selective in ones research to present a more negative picture of any historical character for the sake of it, and therefore just as easy to lose a sense of proportion in exaggerating his or her faults. As a mother and sovereign, she always believed that she needed to respect the best interests of her kingdom on one hand, and the personal needs of her children and their families on the other. It was a delicate balancing act, and mistakes were inevitably made. Credit has to be given to any parent faced with often conflicting demands, particularly one who did not have the benefit of a happy childhood themselves. Hers was a lonely, difficult upbringing in a single-parent family. Her widowed mother, the Duchess of Kent, was a stranger in a strange land with a poor command of English, a woman with a strong moral compass, dominated by her secretary and comptroller John Conroy, who ruthlessly tried to manipulate her and her small daughter for his own ends, and surrounded by a family whose attitudes towards her varied between friendliness and profound suspicion. Victoria had no other family, apart from two much older half-siblings living in Germany, whom she rarely saw.

When it came to bringing up her own family, seeing them marry and have families of their own, she had no role model apart from a husband whose own early life had likewise been a sad one, largely without the presence of a mother, and who, like his mother, died unexpectedly young. No family is perfect with regard to its relationships, and that of Queen Victoria (as well as Prince Albert) was anything but perfect. She had her faults; prone to favouritism, she did not always understand high-spirited youngsters; she could be, and often was, very demanding, and on occasion remarkably tactless. Yet she was also capable of great generosity, and understood when her adult sons and their wives were in particular trouble, not necessarily of their own making.

Part I

The Early Victorian Years 184074

Chapter 1

On 10 February 1840 Queen Victoria married Prince Albert, second son of Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Coburg Gotha. Both were grandchildren of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, whose children included Duke Ernest, King Leopold of the Belgians, and Victoria, who had married firstly Emich Charles, Prince of Leiningen, and after his death Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, fourth son of King George III. The duke died suddenly of pneumonia in January 1820, leaving Victoria a widow for the second time, after only eighteen months of married life. The future queen was only aged eight months at the time.

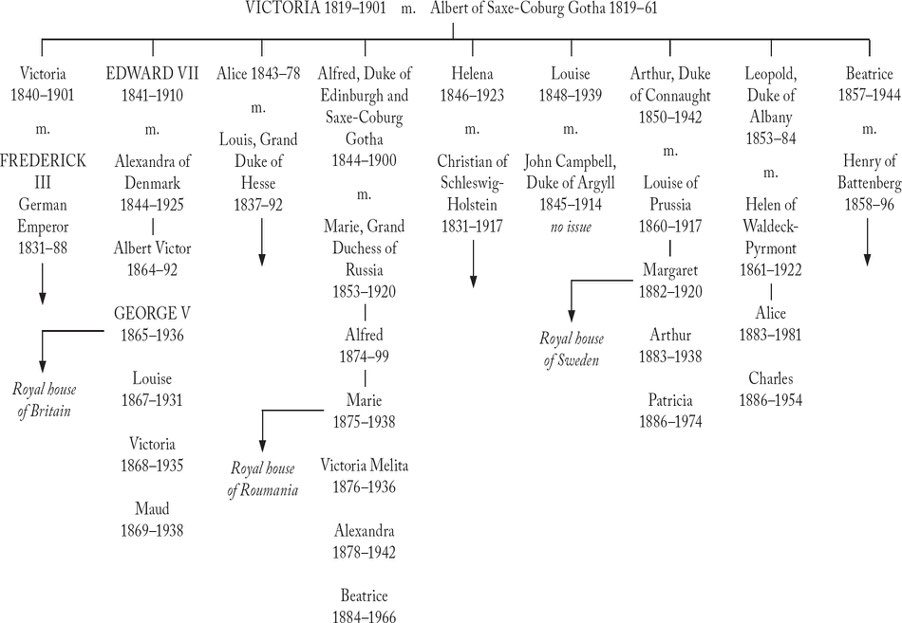

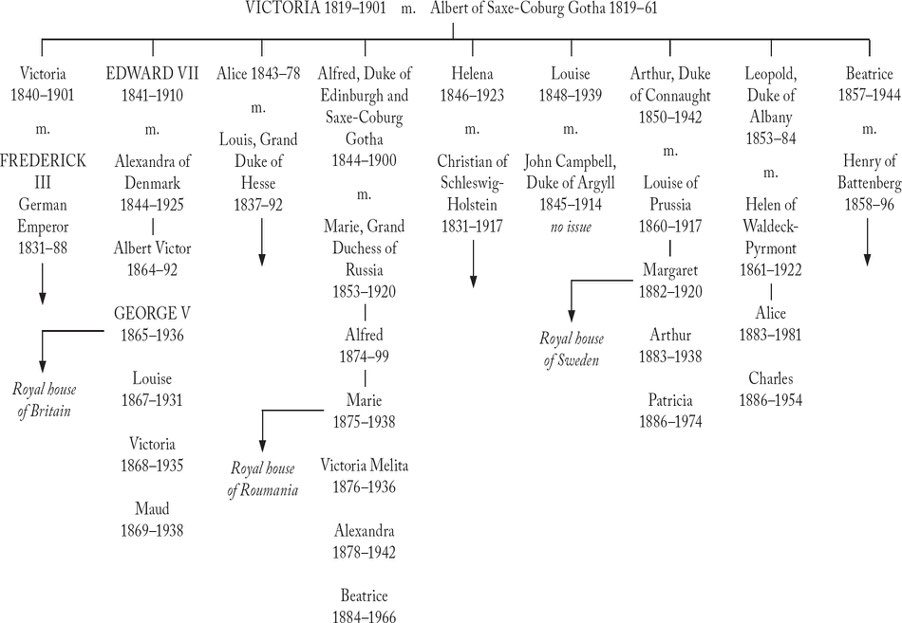

Victoria and Alberts first child, Victoria, Princess Royal (Vicky), was born on 21 November 1840. When told that she was the mother of a princess, the slightly disappointed queen assured the doctor that the next would be a prince. She kept her word. Within three months she was enceinte for the second time, and on 9 November Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, was born. The pattern was maintained with another daughter, Alice, on 25 April 1843, and a second son, Alfred, on 6 August 1844. After two more daughters, Helena on 25 May 1846, and Louise on 18 March 1848, came Arthur, the third son, on 1 May 1850, and Leopold, the fourth, on 7 April 1853. The family of nine was completed with the birth of Beatrice on 14 April 1857.

Next page