Pagebreaks of the print version

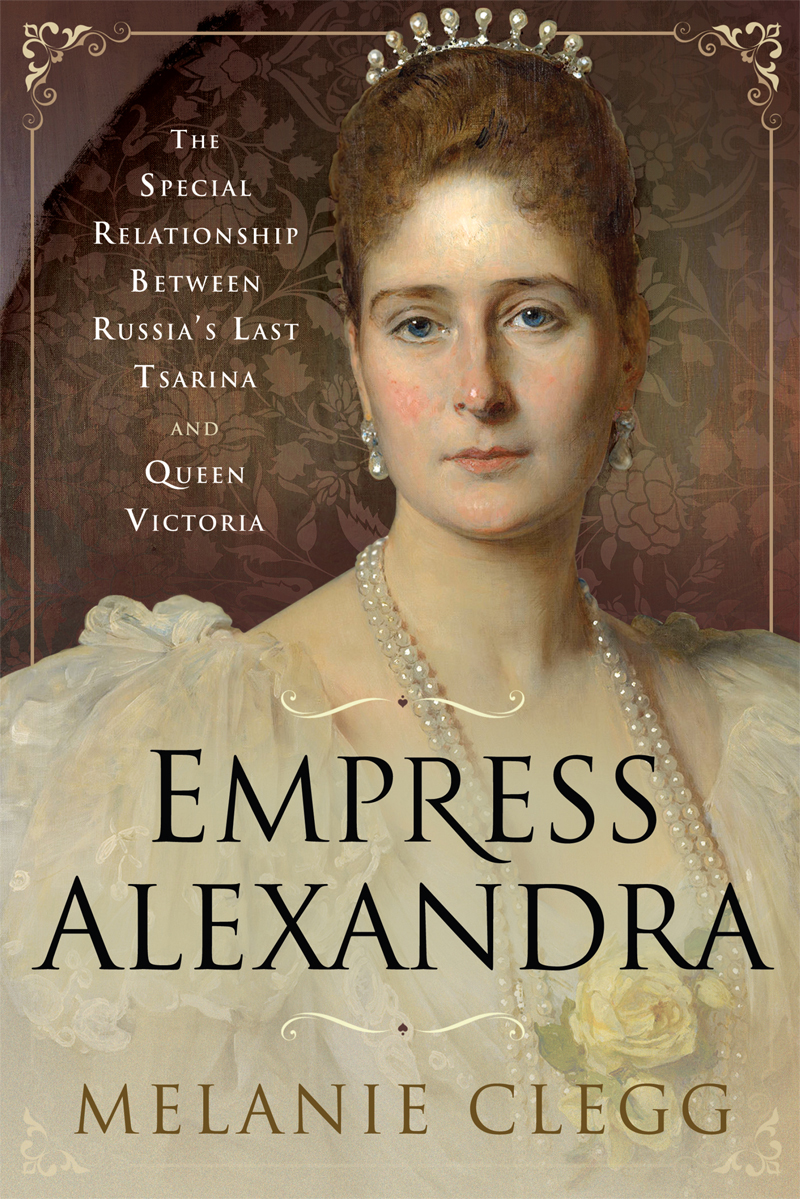

Empress Alexandra

This book is dedicated to David Hayden, beloved husband and father, bon vivant and passionate lover of history.

(19412020)

Dieu nous a donn le vivre;

cest nous de nous donner le bien vivre Voltaire.

Empress Alexandra

The Special Relationship Between Russias Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria

Melanie Clegg

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Melanie Clegg 2020

ISBN 978 1 52672 387 1

eISBN 978 1 52672 388 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52672 389 5

The right of Melanie Clegg to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Chapter One

A dear, good, amiable child.

18421855

T he summer of 1842 was the hottest one that anyone could remember, with even the young Queen Victoria complaining about the overpowering heat) and larking about in the royal nursery with their children, eighteen-month-old Victoria (a precocious and adorable little girl known in the family as Pussy) and her younger brother Albert Edward (a sickly child who was known simply as Baby). However, outside their privileged bubble of dinner parties, concerts and family holidays, civil unrest was sweeping across the nation in the form of strikes and riots, which would ultimately involve over half a million workers in coal mines, factories and mills downing tools and protesting wage cuts and poor conditions. Victoria was kept fully briefed about the situation by her Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel and wrote about the dreadful accounts of rioting in her journal. Meanwhile, closer to home she was anxious about the health of her former Prime Minister Lord Melbourne, who suffered a stroke towards the end of the year, and the premature death of the thirty-one-year-old Ferdinand Philippe, Duc dOrlans, eldest son and heir of King Louis Philippe of France, who was accidentally killed in a carriage accident in July 1842. The Ducs wife Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was a cousin of both Victoria and Albert and they therefore took a great interest in the tragedy as it unfolded across the Channel in France.

Victoria was twenty-three years old and had been married to her first cousin Albert of Saxe-Coburg Gotha since February 1840. They had only met a handful of times before their wedding and remained blissfully in love, although the disparity in their fortunes and Victorias determination not to surrender any of her authority to her husband, inevitably resulted in conflict. The early years of the couples marriage were marred by a series of epic rows as Albert expressed his frustration and Victoria failed to understand his unhappiness and bristled at what she perceived to be his implied criticism of her ability to rule alone. By the summer of 1842, however, the couples relationship was far more harmonious as both developed a greater understanding of the others character and Victoria, keen to see Albert shine in public life, gave her husband more responsibilities. The arrival of their children also did much to reconcile the couple, not least because Victorias pregnancies gave Albert an opportunity to step in and shoulder some of her work while she was either indisposed or recovering from childbirth. In contrast to her modern reputation as an uninterested mother who resented and bullied her children and found them utterly repellent when they were babies, Victoria was enchanted by her eldest child Vicky and her journals are full of updates about her daughters health and progress and how pretty she looked when she was brought downstairs in one of her favourite velvet frocks, which were often gifts from Victorias mother, the Duchess of Kent. When Bertie came along a year after his sister, he too was greeted with joyous relief by his adoring parents and there is no hint of his mothers later antipathy towards him in her descriptions of his infant beauty, her constant worrying about his poor health or her proud recording of various childhood milestones such as his first steps or the eruption of his first teeth. In fact, it is clear that Victoria, aside from the pressures that her position placed upon her, was much like any other new young mother and was thoroughly enchanted by her eldest children.

In the early autumn of 1842, Victoria and Albert embarked on an adventure that they had been looking forward to for quite some time their first visit to Scotland. In the early stages of their rather unusual courtship, they had bonded over a shared passion for the romantic historical novels of Sir Walter Scott, which were mostly set in the Borders region of Scotland. Victoria longed to see Scotland with her own eyes, while the and indeed, the couple had already resolved to return as soon as possible, although another decade would pass before Albert purchased their own piece of the Highlands when he bought Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire as a holiday home for their growing family.

Victoria had probably already guessed that she was pregnant again in the middle of August just before they set off on their Scottish adventure, but made no explicit mention of the fact that she was expecting another child in her journal (although it is also a possibility that the intimate details of her pregnancy were removed when her youngest daughter Princess Beatrice heavily edited her mothers journal after her death in January 1901) until 11 March 1843, when she checked over the linen and clothes that had been used for her last two babies, pronouncing it in the best state and noting that there was hardly anything more to be ordered of her condition are the occasional references to after dinner naps and the fact that her regular rides were replaced by rather more sedate outings in a carriage with Prince Albert taking the reins. Victorias third pregnancy certainly seems to have been as uneventful as her previous two, although she was plagued by a persistent cold for several months, which greatly annoyed the usually robust queen, who rather prided herself on her rude good health. On the 23 March, a month before she expected her baby to be born, Victoria very regretfully ended a family holiday to her uncle Leopolds mansion Claremont in Surrey (where, incidentally, her first cousin Princess Charlotte had died in childbirth in 1817) and begrudgingly returned to Buckingham Palace for her lying in, predicting that she would not be allowed to leave the capital for quite some time.