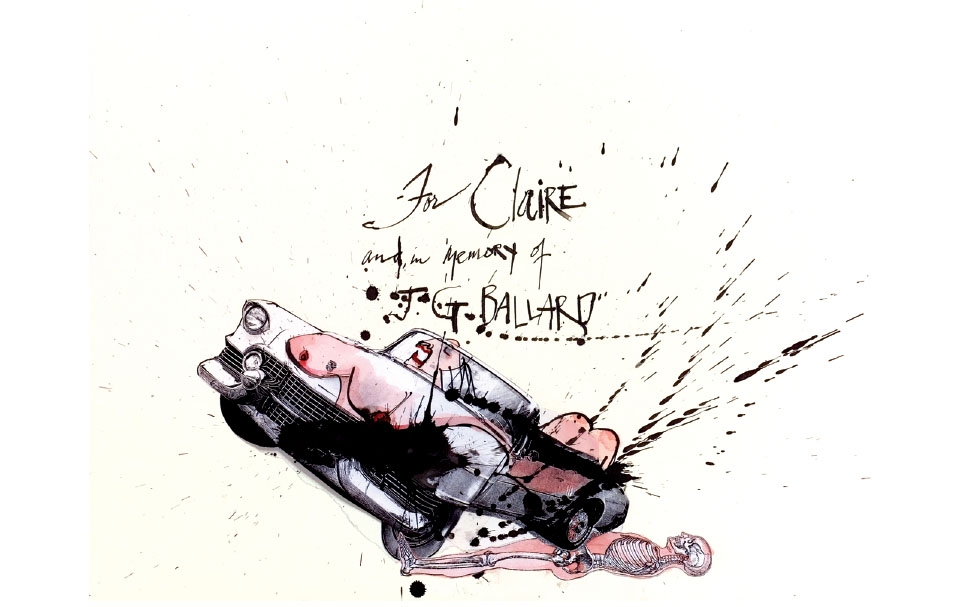

I decided to walk to The World from J. G. Ballards house in Shepperton. Jim had been in hospital over Christmas the chemical refinery of the Hammersmith, which faces out over the veldt-in-urb of Wormwood Scrubs and the experience had nearly done for him. They were suggesting he move to a single room at the end of the ward, said Claire, his girlfriend, and you know what that means. Of course I did: 90 per cent of the spending on healthcare in any given English individuals life takes place in the last six weeks of life, up until then welfare provision may have been patchy, but a citizens final demise is invariably on full-board and en suite assuming, that is, express checkout.

Claire extracted Jim from the hospital and took him back to her flat in Shepherds Bush. I could picture the rhythms of this phase of their lives together, the coming and going of the district nurse, the pitter-patter of tiny pills. When I spoke to Claire on the phone she remained simply delighted to have wrested him from the clutches of hospital medicine with its all too often pointless heroism and to have restored him to a domestic context. Ballard, the most outlandish of fictional imaginers, had always dug out his wellspring by the hearth, and remained the perfect exemplar of Flauberts dictum: a bourgeois in his life, a revolutionary in his dreams.

Claire worked at her computer during the days, a baby alarm next to her mouse mat so she could hear if he needed anything, then, when it was time to go to bed she took it with her. When I take it upstairs, she wrote to me, its as if Im carrying his breathing self in the little plastic machine. I hold it very carefully in my hand, like a precious living thing... (I havent told him). I found this quite unbearably affecting; indeed, I had become involved in all of this in a way I found both difficult to understand and painfully obvious.

I had propped up a copy of Jims memoir Miracles of Life on the bookcase in the kitchen, so that each morning, on coming downstairs, I was met by the image of the child Ballard, riding his tricycle in Shanghai. I felt myself opening out to the numinous in my communion with the dying writer, an intimation of alternate realities, including, perhaps, some in which we had been as close emotionally and physically as we had been imaginatively; for, to pretend to an intimate relationship with Jim wouldve been presumptuous we had met at most five or six times.

The first had been in 1994, when Ballard was publishing Rushing to Paradise, his warped eco-parable version of The Tempest, wherein Greenpeace activists and South Seas sybarites run amok on an atoll used for nuclear weapons testing. Like so many before me, I had made the pilgrimage to the Surrey dormitory town of Shepperton to interview its sage for a newspaper. All was as has been described in scores of articles: the neat little semi along the somnolent suburban street, the mutant yucca straining against the curved mullions of the front window, the Ford Granada humped in the driveway. Inside, the small rooms were dominated by the reproductions of lost Paul Delvaux nudes that Jim had commissioned himself; other than this oddity the decor was an exercise in unconcern and not a studied one.

Would you like a drink? he asked, vigorous in an open-necked white shirt. Ive got everything.

I had had, of course, a fantasy of quaffing Scotch with Ballard I knew of his legendary and unashamed consumption: the first tumbler poured in the morning when he returned from the school run, the leisurely topping-up throughout the writing day, two-fingers-per-hour, clackety-clack, as his fingers gouged their way into inner space. However, like a lot of alcoholics I couldnt risk taking a drink in the afternoon especially if I was working the comedown was instant, I would have to have more and more; no leisurely sousing but a sudden spirituous downpour, so I asked, Can I have a cup of tea?

Jim grimaced: Too much trouble, boiling water and things... he gestured vaguely.

I settled for water. We sat down in the back sitting room, looking out through French windows to a sunlit garden. Jim chortled, So, youve managed to extricate yourself from that cocaine-smuggling business have you?

He was referring to a recent bust Id had for possessing hashish in the Orkney Islands, where Id been living up until a couple of months previously the case had recently been heard at the Sheriff Court in Kirkwall, and made a few column inches down south. I explained the situation but he seemed utterly uninterested in the detail: possession/supply, hash/coke it was, his manner suggested, all one to him. I found myself strangely bothered by how dgag Ballard was, as if it was his responsibility to either condemn or condone my actions. It was absurd; true, he was thirty-one years my senior but I was a grown man, besides, he wasnt my father; or, at least, not biologically.

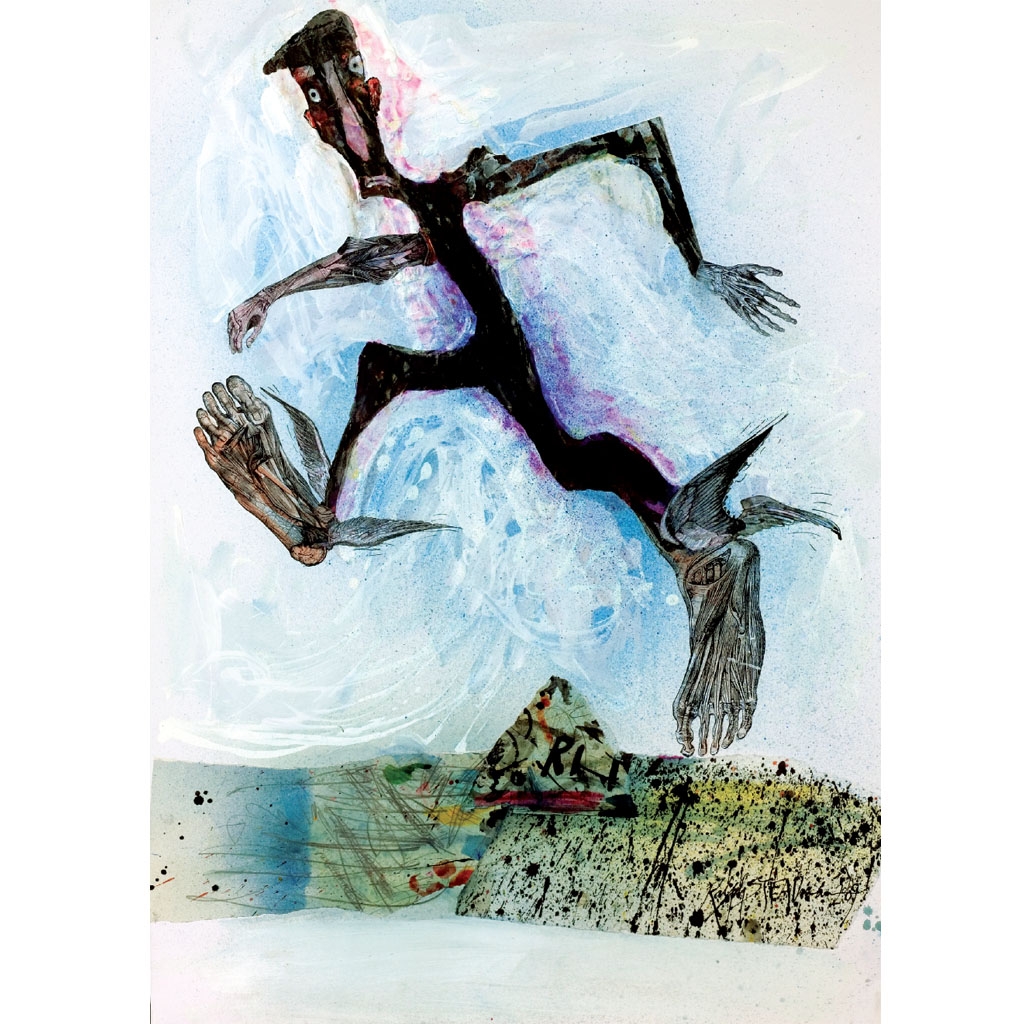

For that was the problem, as well as the abiding infantilism of my own malaise the need to blame everyone else for my own derelictions, my ethical pratfalls and emotional incontinence I also believed I was Ballards mind-child, that my hypertrophied creative impulse had burst from his domed forehead, slathering his remaining greyish hair with amniotic fluid. Its a sensitive business, this one of literary patrimony although Id never had any anxiety about my influences. There were those writers whose work spoke to me, those whose mannerisms, tropes, accidents of style were in Audens memorable acronym GETS, Good Enough to Steal and then there were a very select few who had carved out the conceptual space within which I sought to stake my own claim. Of these, Ballard was the pre-eminent.

The great wind from nowhere of October 1987: I awoke in a sepia dawn to a cacophony of tortured metal; through the Venetian blind slats I could see that six by three-foot panels of corrugated iron were being torn from the scaffolding on the old LCC block opposite. The zephyr was strong enough to be holding some upright and push them along the road surface, striking sparks. Nature, kept away from the city by its mighty radiation repelled by roofs, walls and fences had broken through. Except that in this mundane urban context the wind no matter how strong could not possibly be from nowhere, only a little further north, say Camden Town.

I associate my Ballardian apprenticeship with this period, in my middle twenties, when, recently sprung from four months in rehab, I shared a flat on the Barnsbury Road in Islington with an elfin would-be mime artist. We painted the floors red and listened to southern soul on an antiquated valve record player; occasionally my flatmate did a handspring a manoeuvre he had used to evade the bulls in Pamplona.

I was nervy and racked by caffeine and nicotine one morning I even overdosed on coffee, no mean achievement. I had a writerly girlfriend who was more advanced than me shed actually completed a novel, and in due course it was published. I found it difficult to get at her: after sweaty midnights, then throughout those cold dawns I struggled to prise apart her thin and resistant white limbs. I recall the feel of hand-me-down parental linen and sinking into the trough of a broken-backed bed dragged back from the furniture warehouse on the Liverpool Road. She turned away from my carefully crafted caresses and I saw peculiar spiral markings on her bare back and stubby neck. Ring worm. We both had it the vermiculation of our short-let accommodation had bored through the plaster and into our flesh.