The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him.

Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick , by Herman Melville

INTRODUCTION

When John Foster Dulles died on May 24, 1959, a bereft nation mourned more intensely than it had since the death of Franklin Roosevelt fourteen years before. Thousands lined up outside the National Cathedral in Washington to pass by his bier. Dignitaries from around the world, led by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer of West Germany and President Chiang Kai-shek of Taiwan, came to the funeral. It was broadcast live on the ABC and CBS television networks. Many who watched agreed that the world had lost, as President Eisenhower said in his eulogy, one of the truly great men of our time.

Two months later, Eisenhower signed an executive order decreeing that in tribute to this towering figure, the new super-airport being built at Chantilly, Virginia, would be named Dulles International.

Enthusiasm for this idea waned after Eisenhower left the White House in 1961. The new president, John F. Kennedy, did not want to name an ultra-modern piece of Americas future after a crusty Cold War militant. As the airport neared completion, the chairman of the Federal Aviation Authority announced that it would be named Chantilly International. He left open the possibility that a terminal might be named for Dulles.

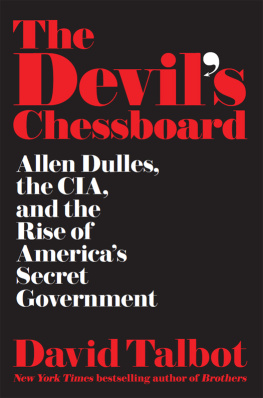

That sent partisans into action. One of them was Dulless brother, Allen, who had run the Central Intelligence Agency for nearly a decade. Pressure on Kennedy grew, and he finally relented. On November 17, 1962, with both Eisenhower and Allen Dulles watching, he presided over the official opening of Dulles International Airport.

How appropriate it is that this should be named after Secretary Dulles, Kennedy said in his speech. He was a member of an extraordinary family: his brother, Allen Dulles, who served in a great many administrations, stretching back, I believe, to President Hoover, all the way to this one; John Foster Dulles, who at the age of 19 was, rather strangely, the secretary to the Chinese delegation to The Hague, and who served nearly every Presidential administration from that time forward to his death in 1959; their uncle, who was secretary of state, Mr. Lansing; their grandfather, who was secretary of state, Mr. Foster. I know of few families and certainly few contemporaries who rendered more distinguished and dedicated service to their country.

Then, in what became a newsreel clip seen around the world, Kennedy pulled back a curtain and unveiled the airports symbolic centerpiece: a larger-than-life bust of John Foster Dulles. It was on a pedestal overlooking an evocative reflecting pool at the center of the airport that the architect, Eero Saarinen, hoped would calm travelers turbulent spirits.

Half a century after Dulless death stunned Americans, few remember him. Many associate his name with an airport and nothing more. Even his bust has disappeared.

During renovations in the 1990s, the reflecting pool at Dulles International Airport was filled. The bust was removed. When the renovation was complete, it did not reappear. No one seemed to notice.

After several fruitless inquiries, I finally tracked down the bust. A woman who works for the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority arranged for me to view it. It stands in a private conference room opposite Baggage Claim Carousel #3. Beside it are plaques thanking the Airports Authority for sponsoring local golf tournaments. Dulles looks big-eyed and oddly diffident, anything but heroic.

Dedicated by the president of the United States while the world watched, now shunted into a little-used room opposite baggage claim, this bust reflects what history has done to the Dulles brothers.

A biography published three years after John Foster Dulles died asserted that he provoked an extraordinary mixture of veneration and hatred during his lifetime, and since his death, in spite of a surge of emotion in his favor towards the end, his memory has remained contentious and intriguing. That memory faded quickly. In 1971 a journalist wrote that although the Dulles name had not been completely forgotten, certainly most of the clat had gone out of it.

John Foster Dulles was, as one biographer wrote, a secretary of state so powerful and implacable that no government in what was then fervently referred to as the Free World would have dared to make a decision of international importance without first getting his nod of approval. Another biographer called his brother, Allen, the greatest intelligence officer who ever lived.

Do you realize my responsibilities? Allen asked his sister when he was at the peak of his power. I have to send people out to get killed. Who else in this country in peacetime has the right to do that?

These uniquely powerful brothers set in motion many of the processes that shape todays world. Understanding who they were, and what they did, is a key to uncovering the obscured roots of upheaval in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

A book tracing these roots could not have been written in an earlier era. Only long after the Dulles brothers died did the full consequences of their actions become clear. They may have believed that the countries in which they intervened would quickly become stable, prosperous, and free. More often, the opposite happened. Some of the countries they targeted have never recovered. Nor has the world.

This story is rich with lessons for the modern era. It is about exceptionalism, the view that the United States is inherently more moral and farther-seeing than other countries and therefore may behave in ways that others should not. It also addresses the belief that because of its immense power, the United States can not only topple governments but guide the course of history.

To these widely held convictions, the Dulles brothers added two others, both bred into them over many years. One was missionary Christianity, which tells believers that they understand eternal truths and have an obligation to convert the unenlightened. Alongside it was the presumption that protecting the right of large American corporations to operate freely in the world is good for everyone.

The story of the Dulles brothers is the story of America. It illuminates and helps explain the modern history of the United States and the world.

PART I

TWO BROTHERS

UNMENTIONABLE HAPPENINGS

Early every summer morning in the first years of the twentieth century, two small boys awoke as dawn broke over Lake Ontario. Their day began with a cold bath, the only kind their father allowed. After breakfast, they gathered with the rest of their family on the front porch for a Bible reading, sang a hymn or two, and knelt as their father led them in prayer. Their duty done, they raced to the shore, where their grandfather and uncle were waiting to take them out to stalk the wily smallmouth bass.

Never have a couple of catboats on any lake held three such generations. The old man with billowing sideburns had been Americas thirty-second secretary of state. His son-in-law was on his way to becoming the forty-second. As for the two boys, they would ultimately outshine both of their illustrious fishing partners. The elder, John Foster Dulles, would become the fifty-second secretary of state and a commanding force in world politics. His brother, Allen, would also grow up to shape the fate of nations, but in secret ways no one could then imagine. Later in life he came to believe that his interest in espionage was shaped in part by the experience of finding the fish, hooking the fish and playing the fish, [working] to draw him in and tire him until hes almost glad to be caught in the net.

Next page