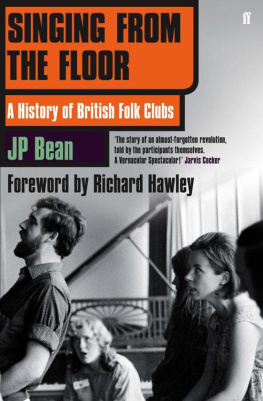

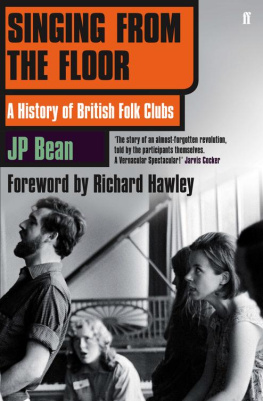

Rock n roll was the world I grew up in. I never went to folk clubs in their heyday, I was too young but I heard stories about them from my dad. So when my pal JP Bean showed me a book he was writing, Singing from the Floor the book you, dear reader, now hold in your hands I was fascinated and excited about it. I love the idea of singers and musicians non-musicians, too without managers or agents or record companies, playing in rooms above pubs, all joining together to sing old songs about good and bad times and new songs protesting about the way governments and tyrants can destroy the future songs and tunes that form our heritage.

This book tells the story of a movement a music scene that was not very well organised, to say the least; that was, it has to be said, homespun, anarchic and totally devoid of any commercial motives, for a time: four reasons, then, for newcomers to love it and totally embrace it as a way of life, which many thousands of young, and eventually old, did.

It is the story in their own words of how a few devoted folk music fans and musicians helped launch one of the biggest revolutions musical, political and social this country has ever seen. This is the birth of the counterculture we now take for granted. There would arguably be no punk without it. The songs those remaining dedicated men and women still sing often tell the stories of the losers in historys great battle I hope this book will go a long way to help preserve the stories of the great battles those men and women fought themselves, so that they wont be lost to us for ever. Enjoy, and dont forget to hand it down.

Introduction

Times have changed within the British folk scene. Once, back in the heady days of the sixties and seventies, folk clubs abounded all over the country. Now, while they have not disappeared altogether, they are thin on the ground. At the peak of the folk revival, there were hundreds of clubs in and around London, seventy-two on Merseyside, a club seven nights a week in most of the big cities. Every town and many a village had a folk club. In the universities and colleges they flourished. In Edinburgh there was even one in the police social club.

Most clubs met weekly in smoky rooms above pubs, bare rooms with battered stools and beer-stained tables, where the stage was no more than a scrap of old carpet and a sound system was unknown. The organisation was amateur there was little money around; it was all about enthusiasm.

Back then, folk club audiences were young. They didnt expect comfort. They were there to see and listen to a booked singer or group do two half-hour spots, as well as the clubs resident singers or occasional performers who might drop by. Everyone joined in the choruses, humour prevailed and much drink was taken.

Now, the folk scene is different. Many of the clubs that have survived are in effect mini concert venues. Resident singers and locals who used to get up and sing from the floor have been replaced by performers with no regular link to the club, booked in advance along with the main artist. At the other end of the spectrum are clubs that have become singarounds with a guest booked only a few times a year.

Today, folk enthusiasts go to arts centres and concerts rather than clubs. In their thousands they flock to festivals. In the old days their parents, when they were young and the music was fresh and before commercialism crept in, went to folk clubs.

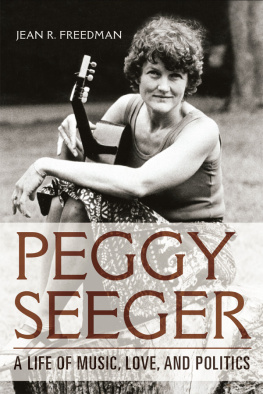

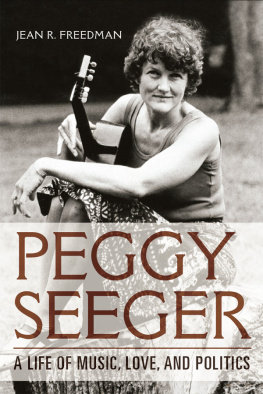

When the folk revival began in the fifties, as many people whose voices are heard in this book will tell, the scene was driven by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and by left-wing activists like Ewan MacColl, Alan Lomax, A. L. Lloyd, Bob Davenport, Karl Dallas, Peggy Seeger and John Foreman. Folk singers, with few exceptions, did not belong to the establishment. They stuck to their ideals.

When I started going to folk clubs, in Sheffield in 1966, the big night of the week was Saturday at the Barley Mow, above the Three Cranes pub. The L-shaped room held about forty people comfortably, but up to 140 crammed in sitting, squatting, standing, wedged against the walls and perched on the piano.

The organiser and resident singer was Malcolm Fox, a genial fellow in his mid-twenties who discovered folk music through the Young Communist League and CND marches. He was full of enthusiasm and went out of his way to encourage others. He would give any floor singer an opportunity and, although his own preference was traditional song, he placed no restrictions on what anyone sang and he booked the best guests around at the time.

To a callow youth of sixteen, the Barley Mow was a marvellous place to be. The atmosphere was so cheery, boozy and upbeat that every Saturday night seemed like Christmas Eve. In the first few months alone I saw performers who made impressions that have never left me: Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger addressing the audience as if it were a class; Bob Davenport, whose mighty unaccompanied voice and Geordie songs captivated the room for a whole evening without any instrumental backing; the truly awesome Alex Campbell, who could hold an audience better than anyone Ive ever seen; Pete Stanley and Wizz Jones a frock-coated banjo player and a long-haired, bespectacled beatnik with an ancient guitar that was held together with sticky tape.

Other clubs followed: there were great nights at the Highcliffe Hotel, where Ralph McTell and John Martyn were regular guests and where Barbara Dickson and the Humblebums made their south-of-the border debuts. I saw the Watersons there, and the old bluesman Reverend Gary Davis, but my most vivid memories are of being rendered helpless with laughter by Tony Capstick, who Id got to know earlier at the Barley Mow.

Capstick, when I first met him, was twenty-two and not yet a professional folk singer. He looked like a bookies runner in his brown checked suit and old plimsolls and he played the banjo and sang a lot of Irish songs, but it was his amazing wit and inventive humour that grabbed attention. He was the funniest man Id ever met.

The years went by and I didnt go to folk clubs so often. I was focusing on writing and had several non-fiction books published. Tony Capstick became one of the most popular performers on the national scene. One day in the late eighties I heard him on the radio in an obituary to Alex Campbell, a man who had probably played every folk club in the land.

As Tony rolled out stories of Alex and the colourful life he had lived in the folk clubs and busking on the streets of Paris, it occurred to me that there was very little written about Alex Campbell, and while many people had memories of him, they would eventually be lost.

Later, in the mid-nineties, I mentioned these thoughts to Tony. We talked about how the folk scene had been neglected in permanent print and I suggested that he should write a book about his life in the folk clubs. He had a column in a local paper and could write as articulately and humorously as he spoke. Needless to say, he never did and in 2003 he too died, taking forty years of songs, anecdotes and memories with him.

The folk scene had moved on. Some of the old stalwarts of the clubs had disappeared from the fray. Some had become famous, some had died. Others were growing old. So, deciding that action was needed before it became too late, in early 2010 I took it upon myself to seek out performers, club organisers, record producers and other relevant parties who had been involved from the earliest days of the folk clubs to the present.