PORTFOLIO / PENGUIN

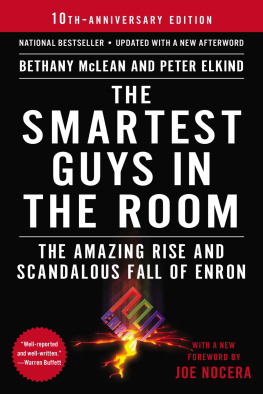

THE SMARTEST GUYS IN THE ROOM

Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind were Fortune senior writers when this book was originally published in 2003.

McLeans March 2001 article in Fortune, Is Enron Overpriced? was the first in a national publication to openly question the companys dealings. She now lives in Chicago with her husband, Sean Berkowitz, who was the head of the Enron Task Force when they met in 2006. McLean is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and a columnist at Reuters.

Elkind, an award-winning investigative reporter, is the author of The Death Shift and Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer. A former editor of the Dallas Observer, he has been an associate editor at Texas Monthly and written for The New York Times Magazine and The Washington Post. Now editor-at-large at Fortune, he lives in Fort Worth, Texas.

For Chris

B.M.

For Laura

P.E.

PORTFOLIO / PENGUIN

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by Portfolio, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2003

Updated paperback edition published 2004

This edition with a new foreword and afterword published 2013

Copyright 2003, 2004 by Fortune, a division of Time, Inc.

Foreword copyright 2013 by Joe Nocera

Afterword copyright 2013 by Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted works: Hotel Kenneth Laya by James A. Hecker, 1995 James A. Hecker. Used with permission; Perfect Day by Tim James and Antonina Armato, 2001 WB Music Corp., Out of the Desert Music, and Tom Sturges Music o/b/o Antonina Songs. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc. and Tom Sturges Music.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

McLean, Bethany.

The smartest guys in the room : the amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron / Bethany

McLean and Peter Elkind.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-59184-008-4 (hc.)

ISBN 978-1-59184-660-4 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-698-15882-5 (eBook)

l. Enron Corp.History. 2. Energy industriesCorrupt practicesUnited States. 3. Business failuresUnited StatesCase studies. I. Elkind, Peter. II. Title.

HD9502.U54E5763 2003

333.79'0973dc21

Version_1

FOREWORD

In February 2001, as the editorial director of Fortune magazine, I helped edit a short, rigorous storyjust four pages longby a young writer named Bethany McLean, who had joined the magazine some six years earlier from Goldman Sachs and quickly become one of Fortunes brightest stars. Her story was entitled, simply, Is Enron Overpriced?

At its core, Bethanys article asked one very straightforward question: How does Enron make its money? For years the company had been a Wall Street darling, its stock moving steadily upward with each new quarters rising profits. It was seen as the paradigmatic example of a company that had transformed itself from an old-economy stalwartoperating pipelines that moved natural gasto a new-economy marvel, creating dazzling efficiencies and hedging risks (like the weather!) that no one had ever thought to hedge before. Just a month before Bethanys story ran, Businessweek had put Enrons chief executive, Jeffrey Skilling, on its cover, posing with what appeared to be harnessed electricity in his hand, with the cover line Power Broker.

But Bethany had been poring through Enrons financial documents, and what she realized was not just that they were complicated (most big companies have complicated financials) but that they were incomprehensible, even indecipherable. She started calling around to the Wall Street analysts who were so bullish on Enron, asking her simple question.

Some of them told her that Enron was a company you just had to trust. One analyst admitted to her that the companys earnings were a black box. When she reached Skilling himself, the Enron CEO first complained that she didnt get it, something he often said to people who questioned Enron. Then he hung up the phone on her. The Enron public-relations department insisted that if she would just come to Houston and visit the companys headquarters, the fog would soon lift. But with our deadline fast approaching, the Enron PR department decided that if Mohammed wouldnt come to the mountain, they would have to visit Fortune. The company sent a small contingent to New York to meet with Bethany and her editors, including me. Andy Fastow, the companys chief financial officer, led the Enron team.

It would later be blindingly obvious that Fastow had not told us the truthhow could he, given that much of Enrons earnings were the result of accounting manipulations that created the illusion of profitability? But even in the moment it was clear that Fastows goal was pretty much the same as those financials Bethany had been poring through: to obfuscate and confuse. I cant remember all the details, but I vividly recall Bethany asking sharp, pointed questions about the companys business model and Fastow responding with lengthy, nearly unintelligible answers about how Enron was like Toyota, how it should be thought of as a logistics company, etc., etc.even though Enrons main business wasnt actually moving anything from place to place, but rather trading.

And then something happened that Bethany and I would never forget. As the meeting was drawing to a close and the Enron executives were putting on their coats, Fastow turned to Bethany and said, I dont care what you say about Enron. Just dont make me look bad.

It was such a jarring thing for him to say on the eve of what was clearly going to be an unflattering article about his company. In retrospect, it was a tip-offto the mentality of the people running Enron and to the fact that there was indeed something fishy about those financial statementsFastow was, after all, Enrons CFO. It was a real signal that Bethanywhose story wound up raising all the right questions, even if she didnt yet have all the answerswas on to something.

Some articles drop like bombshells. Bethanys wasnt like that. Instead, it slowly seeped into the consciousness of Wall Street. Enrons stock had been in the 70s when Bethanys story was published, not far from its all-time high. Ever so steadily, it began to sink. In April, Skilling was questioned on a conference call by an investor who asked his own tough questions. Asshole, Skilling muttered under his breath. In August, Skilling suddenly and unexpectedly quit as chief executivea move that was all the more stunning because he had taken over as CEO just six months earlier from Enron founder Ken Lay. Though Skilling had effectively been running the company for years, everyone knew how much he had wanted the actual title of chief executive. His resignation triggered a flurry of skeptical stories and questions.