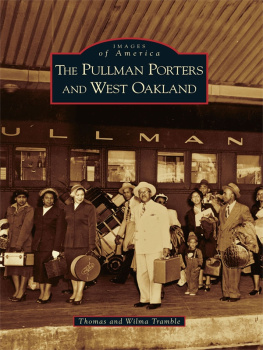

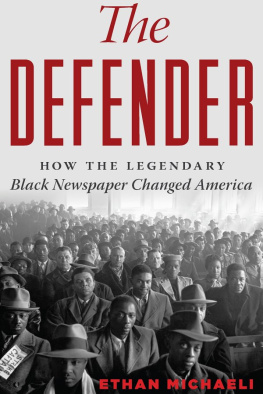

THE MOST INFLUENTIAL black man in America for the hundred years following the Civil War was a figure no one knew. He was not the educator Booker T. Washington or the sociologist W. E. B. DuBois, although both were inspired by him. He was the one black man to appear in more movies than Harry Belafonte or Sidney Poitier. He discovered the North Pole alongside Admiral Peary and helped give birth to the blues. He launched the Montgomery bus boycott that sparked the civil rights movementand tapped Martin Luther King Jr. to lead both.

The most influential black man in America was the Pullman porter.

For millions of whites who rode the sleeping cars west toward San Francisco or south to Florida, the porter was the African-American man they mixed with more than any otheryet understood not at all. They did not know that scores of men like the North Pole pioneer Matthew Henson and the blues legend Big Bill Broonzy had worked on sleepers until they earned enough money and confidence to try something else. They saw porters serve as props in hundreds of films, but few realized porters starring roles as patriarchs of black labor, or in financing and orchestrating the civil rights struggle from Montgomery right through the 1963 March on Washington. And no one calculated porters most lasting legacy: activists like NAACP boss Roy Wilkins, political leaders like Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley, artists like jazz great Oscar Peterson, and all their otherchildren and grandchildren, nephews and nieces, who run universities and municipalities, sit on corporate and editorial boards, and helped spawn and shape todays black middle class.

If whites did not grasp that, they can be excused. Few blacks did, either. In his earliest years the Pullman porter was seen in the black world as a figure whose very presence captured the romance of the railroad, a traveling man with cosmopolitan sensibilities and money in his pockets. But by the 1960s he had come to personify the grinning servant, an Uncle Tom transplanted from plantation to locomotion. Neither image was complete. Behind the porters constant smile and courtly service lay a day-to-day struggle for dignity that anticipated black Americas bloody crawl toward equity. If race is the story of America, the Pullman porter represents one of its most resonant chapters.

Yet while the nations racial history is an unwieldy story, one that convulsed the country from its most remote corners to its most public spaces, the tale of the Pullman porter unraveled within the narrow confines of a railcar and thus can serve as a kind of historical prism. It was a capsule of space and time where all the rules of racial engagement came into succinct and, at times, painful focus. Sometimes they were suspended altogetheras long as the train was moving, that is. The porters story extends from the end of the Civil War to 1969, when the Pullman Company terminated its sleeping car service, which lets us see how those close contacts between the races evolved over a complete century.

I came to this story by accident. Ten years ago, when I was a Nieman fellow at Harvard University, Professor John Stilgoe used the Pullman porters to help explain the shaping of Americas landscape and culture. Porters were agents of change, we learned, much the way Jewish peddlers had been in the shtetls of Europe and small towns across the United States. They carried radical music like jazz and blues from big cities to outlying burgs. They brought seditious ideas about freedom and tolerance from the urban North to the segregated South. And when white riders left behind newspapers and magazines, porters picked up bits of news and new ways of doingthings, refining them in each place they visited, and leaving behind a town or village that was a bit less insular and parochial.

What they saw and read changed them, too. It made porters determined that their children would get the formal learning they had been denied. Whom they met was even more transforming. Most people who rode Pullman cars have only vague memories of their porters, albeit pleasant ones. The porters, by contrast, were keen observers of the politicians and movie stars, businessmen and leisure travelers, who boarded their trains. They shined their shoes and marveled over the careful stitching and soft leather. They took their orders and noticed the meticulous phrasing and mannered expressions. Through their time on the train these black porters learned the ways of a white world most had only vague exposure to before, coming to know how it worked and how to work with it. All of which helped fill in their expanding sense of self-esteem and power. I dont know if you ever heard about the three Ls , because L stands for so many things, explained Jimmy Clark, who worked as a chef on the Pullman cars from 1918 to 1950. But these three Ls was look, listen, and learn. And those things imbedded into my mind to the point where I lived with it, and it helped me all through this world, and its helping me to this day.

Professor Stilgoes preoccupation with such porter stories quickly became mine. It stayed with me when I returned to the Boston Globe and understood in a new way how critical race was to so many issues I wrote about, from Pentecostalisms becoming the fastest-growing religion in the world, and especially in the black community, to why Boston still cherishes its forty-year-old program for busing inner-city blacks to largely white suburban schools. My first book, The Father of Spin, taught me how biography can tell a bigger story, specifically how spinmeisters like the public relations pioneer Edward L. Bernays help determine Americas commercial choices and public discourse. My second book, Home Lands, on the renewal under way across the Jewish world, helped me see how religion and race can furnish identity and hope.

Pullman porters embrace all that. They are men whose compellingbiographies tell bigger stories of racial dynamics, democracy, and the building of African-America. Not only are they a singular tale of history; they are one that is living and breathing today. Behind almost every successful African-American, there is a Pullman porter.

Or so it appeared as I cross-checked porters against lists of prominent black scientists and artists, political and business leaders. One in every few had a porter father or grandfather, uncle, cousin, or in-law. Others had worked on the sleepers themselves. The theory that porters fueled black advancement seemed true beyond what I had imagined. But it was equally clear that such progress came at an enormous price. For every inch the porter gained there was a humiliation to endure. The very definition of his job was roiling in contradictions. He was servant as well as host. His was the best job in his community and the worst on the train. He could be trusted with white passengers children and safety, but only for the five days of a cross-country trip. The Pullman porter shared his riders most private moments, but, to most, he remained an enigma if not a cipher.

To fill in that puzzle I had to find and talk to porters, which was a challenge. Every source I consulted said there were only a handful left in the country, which made sense since the Pullman Company had been out of business thirty years and had hired very few porters for the thirty before that. I tried to track them down using every technique I learned during twenty years as a journalist in Boston, Louisville, and Anniston, Alabama. I posted ads in black papers, railroad journals, and retirement magazines. I scoured retirement records the company left behind in Chicago, then wrote to every porter there was a chance could still be alive. High-tech detective agencies ran searches at ten dollars a shot, Amtrak scoured its files and collective memory, authors who had written about porters or their union offered up contacts, and interns helped me contact black politicians, ministers, civil rights leaders, and nursing home administrators across the United States.