Houdini

The Ultimate Spellbinder

Tom Lalicki

For Barbara

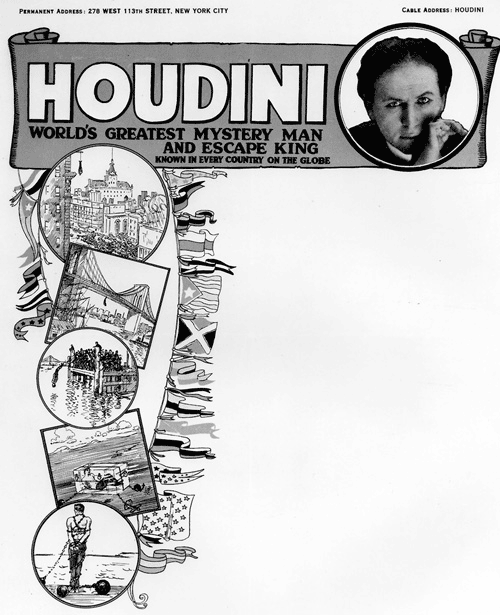

Houdini is surrounded by illustrations of the mysterious, magical, death-defying feats that made him legendary.

One of the many letterheads Houdini designed for his correspondence.

The Greatest Novelty Mystery Act in the World!

In 1876, when Mayer Samuel Weiss sailed to seek his fortune in the New World, his hopes for the future must have been mingled with sad, ness and regret.

Trained as a lawyer, he could not practice law in his native city of Budapest because he was a Jew. He became a biblical scholar and a rabbi but could not find a congregation in Hungary. To make a life for his wife and five sons, Rabbi Weiss came to the United States alone. It took him two years to find a position.

Most Americans were Christians in 1876. The massive immigration of Eastern European Jews (and southern European Christians) started in the 1880s. Between 1880 and 1925, over 25 million people came to the United States "The Golden Landto escape poverty and persecution. Not all the immigrants intended to stay. Called Birds of Passage, many intended to make their fortunes and go home rich. Over one,third of all those immigrants did return to Europe, but almost none of them had become rich. They went back because making a life in America was just too hard for them.

In 1878, the Weiss family was reunited. The rabbi's wife, Cecilia, who was twelve years younger than Mayer, brought their four sons: Nathan, William, Ehrich, and Theodore. Herman, Weiss's oldest son from a previous marriage, came with them. Herman's mother, Mayer's first wife, had died years earlier. Two more children would be born in the United States: Leopold and Gladys.

Rabbi Weiss shepherded a small congregation in Appleton, Wisconsin, that worshiped in a room borrowed from a local club. Appleton was a beautiful, prosperous town. Its farmers grew wheat and its loggers cut trees to make paper. Appleton had a college, public parks, open, air concerts, and a welcoming attitude. The synagogue's members were German immigrants. Many of them had been encouraged to settle in Appleton after the Civil War, when Wisconsin and other Midwestern states had sent recruiters to Germany.

An undated photograph of Houdinis father, Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weiss. He was a quiet, scholarly man who never adapted to life in the United States.

Congregation members flourished there, but Rabbi Weiss did not. He and his wife could not adapt to the get-ahead and fit-in mindset of nineteenth century America. They never learned English, the language his congregation members wanted their children to speak, so the congregation let him go. In search of another job, Rabbi Weiss moved his family to Milwaukee.

The rabbi's fifth son, Ehrich, the future Houdini, was a doer from his earliest days. Born on March 24, 1874 in Budapest, an old-world city, he was brimming with new-world energy. By the age of eight he helped support the family by working at street trades: shining shoes, selling newspapers, and running errands. His family desperately needed the money because Rabbi Weiss never found a steady job again. In Milwaukee, they moved five times because they couldn't pay the rent. A Jewish charity helped them out with food and coal.

In the 1880s, most children born in America went to school for seven years. Immigrant children got even less education. Ehrich was no exception, but he learned to read and write and loved to do both all his life.

He also loved to perform. At age nine, he debuted in a backyard circus, which had a five-cent admission, as "Ehrich, the Prince of Air." Decked out in red tights his mother had sewn, he did contortionstwisting body movements and trapeze walking.

Being the intelligent, ambitious son of an educated father reduced to poverty was painful for Ehrich, so painful that he ran away in 1886 to make the family's fortune. He was twelve. His mother, Cecilia, kept a postcard all her life that Ehrich had sent from the road. It said: "I am going to Galvaston, Texas [sic] and will be back home in about a year. My best regards to all.... Your truant son, Ehrich Weiss."

But he boarded the wrong train and ended up in Kansas City, Missouri. From there he worked his way back to Wisconsin by doing odd jobs. He was adopted for several months by the Flitcrofts of Delavan, Wisconsin, and finally made his way back home.

Impressed by his young son's pluck, Rabbi Weiss took Ehrich with him to New York on a job hunt in 1887. New York was the best place in the country for a German-speaking rabbinearly 80 percent of New Yorkers were either foreign-born or the children of immigrants.

They moved into a tenement on East Seventy-fifth Street in Manhattan. Ehrich's father taught German and Hebrew and occasionally performed religious ceremonies, but he could not support his large family. "We lived there, I mean starved there, several years," Houdini later remembered. As an adult Houdini never dwelled, though, on the economic hardships of his youth. He downplayed the family's poverty, writing, "The less said on the subject the better."

As a fabric-cutter in a necktie factory, the teenaged Ehrich shared the misery of the sweatshops. Suits, blouses, glovesevery kind of clothing was made in dark, overcrowded tenements. Sanitary conditions were so bad that tuberculosis was called "the tailor's disease." Immigrants worked ten to fourteen hours a day, six, even seven, days a week. The pay, about three dollars per week, was too little to support a family, so the entire family worked.

Children as young as eight, called "lively elves," were prized by sweatshop owners. Children had nimble fingers for sewing and were easily disciplined. If they didn't take their work seriously enough, the penalties were severe. Looking out a window without permission cost a day's pay.

Most young people were exhausted, if not ruined, by the system. Not Ehrich Weiss. He found time and energy to box in the 115-pound class, to swim in the East River, and to run distance races for the Pastime Athletic Club. And he loved to pick through the used-book bins on Fourth Avenue and haggle over the prices of books he wanted to read. He often read late into the night. He did not seem to think his life was hard.

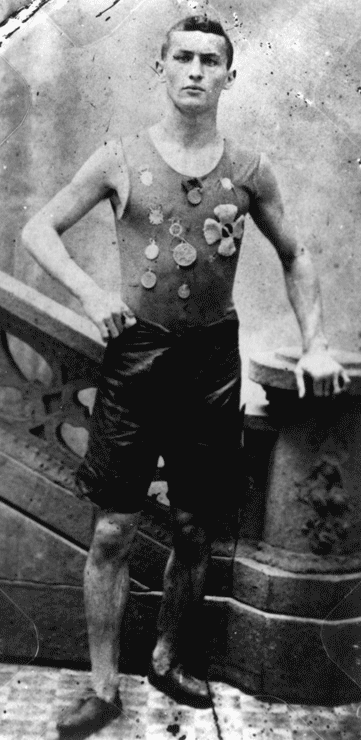

Ehrich Weiss, soon to be Houdini, poses as a confident champion at the age of sixteen. He won the medals for boxing, cross-country running, and swimming in his spare time, after putting in a full day at the factory.

Nobody knows when Ehrich (nicknamed "Ehrie") became seriously interested in magic. He may have given a show in 1890 on a trip to Milwaukee, or he may have debuted in New York that same year. But it's certain that by 1892 "The Brothers Houdini: The Modern Monarchs of Mystery" were professional showmen. And eighteen-year-old Ehrie Weiss was, then and forever, Harry Houdini.

Ehrich had read and loved the memoirs of Jean Eugene Robert- Houdin, known as the father of modern magic. Robert-Houdin had abandoned the age-old wizard's costumeflowing robe and pointed hatfor black evening dress. His conjuring devices were placed on a raised, undraped platform that made trapdoors and help from assistants seem impossible. Ehrich idolized him and wrote, "From the moment I began to study the art, he became my guide and hero. His memoirs gave to the profession a dignity worth attaining at the cost of earnest, life-long endeavor." In tribute, Ehrich adopted and adapted his hero's name. (Later in life, he autographed books: "Houdini. That's Enough." One name said it all.)