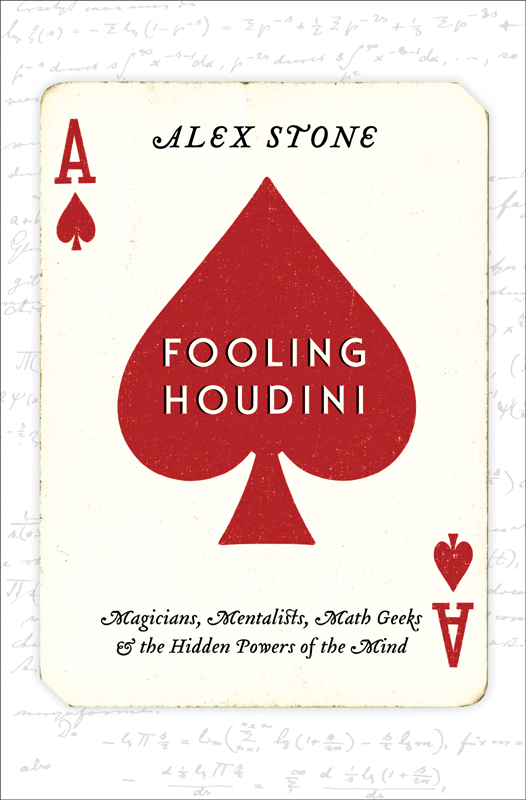

For my parents, Carmen and Bill Stone

The most beautiful thing

we can experience

is the mysterious.

Albert Einstein

Contents

I n the foyer of a hotel in downtown Stockholm, a stunning twenty-two-year-old Belgian girl with dark brown eyes and long chestnut curls had attracted a small crowd. She held an ace in each hand, and as she twirled her arms through the air, the cards transformed into kings. The audience had seen this sort of thing beforethey werent the kind of people who would go wild for a single change. But then, in one fluid sequence, she coiled her wrists again and the kings became queens. The energy in the room quickened as her arms snaked through the air like a flamenco dancersonce, twiceand the queens faded into jacks, then tens. The people around her began to cheer. Another whirl and the tens turned into jokers. She is one of the only magicians in the world who can pull off five transformations in a row, and the audience was now crazy for her.

Toward the back of the lobby, a florid man in a black porkpie hat demoed a shell gamethat age-old gypsy swindle with three hollowed-out shells and a pea. In the corner by the entrance, a gaggle of teenagers in red lounge chairs were performing an acrobatic kung fu of card stunts known as Extreme Card Manipulationa flurry of cuts, spins, and flourishes. In the hands of these kids, the cards became pyramids and snowflakes, whorled mollusk spirals, mandalas of cycling angels. The leader of the group, a chubby alpha nerd in a black skullcap, flaunted a move in which stacks of cards formed intersecting geometric patterns that resembled an M. C. Escher illusion. Then there were the mentalistsmind readers, spoon benders, second-sight acts. Dressed mostly in black, theyd staked out a pair of round tables in the middle of the lounge, and I would have given a kidney to be a fly on one of their beer glasses. Everywhere you lookedin the hallways, at the bar, in the restaurant, by the elevators, even in the bathroomsmen and women were sharing secrets, trading moves. I clutched a worn deck of blue Bicycle cards in my fist and drank in the scene.

It was almost ten oclock on a balmy weekend night in early August, but the Stockholm sky was not yet dark, and a gauzy dusk seeped through the skylights, casting a maze of shadows on the carpet of the atrium lobby. In Sweden during the summer months, the sun hardly sets, and the insomnia of endless daylight can throw you into delirium. Not that I planned to sleep. Here I was sharing the same air with the worlds greatest magicians, many of them my heroes.

We were all in Stockholm for the 2006 World Championships of Magic, otherwise known as the Magic Olympics. Every three years the greatest conjurors from around the globe descend on a chosen city, armed with their most jealously guarded secrets, and duke it out, trick for trick, to see who among them is most powerful. The Twenty-third Olympics in Stockholm were the biggest in history, with nearly 3,000 attendees from 66 countries and 146 competitors vying for medals in 8 events. This year I was one of the challengers.

Given that the Olympics is by far the toughest magic competition in the world, getting into the games at all was something of a miracle. To be eligible, you must belong to one of the eighty-seven magic societies sanctioned by the Fdration Internationale des Socits Magiques, or FISM, the worlds largest and most prestigious magic alliance. The United States has three FISM-approved magic societies: the Academy of Magical Arts, seated at the Magic Castle in Hollywood, the International Brotherhood of Magicians, and the Society of American Magicians, or the SAM (Magic, Unity, Might!), of which I am a card-carrying member.

The entrant must also obtain written authorization from the president of his or her society, and having never competed in an international tournamentor any tournament, for that matterI had been all but certain that SAM president Richard M. Dooley would reject me outright. I was stunned when he wrote back a week after I sent in my request wishing me luck.

I would need it.

I WAS FIVE YEARS OLD when my father, a geneticist and dyed-in-the-wool skeptic who makes his own cologne and brushes his teeth in the car, presented me with an FAO Schwarz magic kit he had bought on a trip to New York for an academic conference. It was a beginners set with a wand and a book and a dozen or so simple tricks. There was a small green plastic cupa miniature gobletwith a ball that vanished, a family of small red foam bunnies that could be made to multiply in your hand, and a small wooden box that turned pennies into nickels. Ill never forget the look of amazement on my fathers face when I showed him my first trick.

My debut gig was my own sixth birthday party, and photographs exist somewhere of me gesturing tentatively, in a top hat and red-and-black cape sewn by a neighbor, before a small group of friends. I was woefully unpolished, and they heckled me to tears. But I didnt quit, thanks in no small measure to my fathers encouragement. Dad was not a religious man. He wasnt into sports or the great outdoors. We never went to ball games or on camping trips. The Chopin tudes I hammered out in our living roomthe product of several years and several thousand dollars worth of piano lessonsrarely elicited more than an absentminded nod from him. But even the simplest magic trick would light up his face. It was a language we both understood. Saturday trips to JCR Magic in our hometown of San Antonioa phantasmagoria of trick coins and dove pans and fake vomitbecame our ritual; magic shows, our sporting events.

One of the biggest treats my father ever gave me was a pair of tickets to see David Copperfield at the ritzy, chandeliered Majestic Theater downtown. Watching the show, I quickly recognized that Copperfield was no mortal. He walked through walls, levitated, vanished astride his roaring Harley, only to appear, seconds later, at the very rear of the theater, proud in his snug leather pants. But the most exciting part of all was that I got to meet the illusionist in person after the performance. Id practiced for weeks what I was going to say to him. I stood in the receiving line in the carpeted lobby of the Majestic for half an hour, worrying over my note cards before coming face-to-face with the unearthly being, he of the feathered hair and flouncy pirate shirt, sitting atop what seemed like a giant throne. When my ten seconds finally came, my vocal cords seized up and the only words that came out were Can I touch you?

By the time I was in high school, Id gotten good enough to start doing paid showsbirthdays, weddings, bar mitzvahs. Mostly I did these shows so I could afford to buy new tricks, the way a junkie deals to support his habit.

In my mind, magic was also a disarming social tool, a universal language that transcended age and gender and culture. Magic would be a way out of my nerdiness. Thats right, I thought magic would actually make me less nerdy. Or at the very least it would allow me to become a different, more interesting nerd. Through magic, I would be able to navigate awkward social situations, escape the boundaries of culture and class, connect with people from all walks of life, and seduce beautiful women. In reality, I wound up spending most of my free time with pasty male virgins.

My interest in magic has only grown since childhood. As I entered the workforceas a fact checker and later an editor at Discover magazinemagic became an escape from the fluorescent anomie of cubicle and commute. Later on, when I started taking upper-level physics classes at Columbia University, with an eye toward applying to graduate school, magic provided a welcome respite from a world bound by logic and empiricism, a relief from my fathers metaphysics. Theres something deeply liberating about letting go of the reins that couple cause and effect, the X and Y axes. Not even wrestling a grungy quantum mechanics problem to the ground could give me quite the same pleasure as mastering a new baffler, and I took an almost perverse joy in stupefying Columbias illustrious faculty.

Next page