KILLER ON THE ROAD

Mark Crispin Miller, Series Editor

This series begins with a startling premisethat even now, more than two hundred years since its founding, America remains a largely undiscovered country with much of its amazing story yet to be told. In these books, some of Americas foremost historians and cultural critics bring to light episodes in our nations history that have never been explored. They offer fresh takes on events and people we thought we knew well and draw unexpected connections that deepen our understanding of our national character.

Ginger Strand

KILLER ON THE ROAD

Violence and the American Interstate

University of Texas Press

AUSTIN

Copyright 2012 by Ginger Strand

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2012

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Strand, Ginger Gail.

Killer on the road : violence and the American interstate / by Ginger Strand. 1st ed.

p.cm. (Discovering America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-72637-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-74210-9 (e-book) ISBN 978-0-292-74456-1 (individual e-book)

1. MurderUnited StatesHistory. 2. MurderersUnited StatesBiography. 3. ViolenceUnited StatesHistory. 4. Interstate Highway SystemSocial aspectsHistory. 5. Express highwaysSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 6. Automobile travelSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 7. United StatesSocial conditions1945 I. Title.

HV6524.S77 2012

| 364.152'30973dc23 | 2011038888 |

CONTENTS

we join our community

in a wordless creed:

belief in individual freedom,

in a technological liberation

from place and circumstance,

in a democracy of personal mobility....

[The freeway] is surely the structure

the archeologists of some future age

will study in seeking

to understand who we were.

DAVID BRODSLY, 1981

from public opinion to motor-car bodies;

and we mass-produce criminals too.

HENRY TAYLOR FOWKES RHODES, 1937

KILLER ON THE ROAD

Introduction

KILLER ON THE ROAD

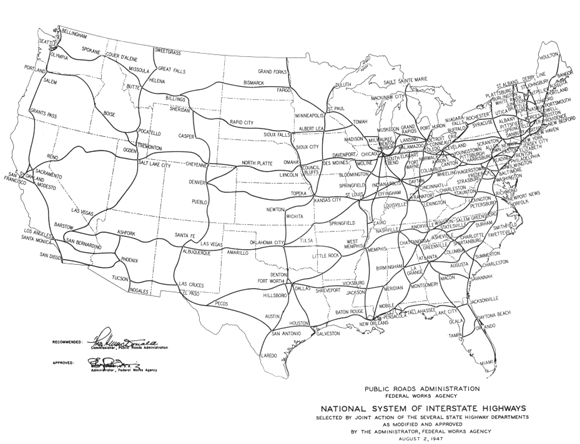

In the mid-fifties, Congress transformed how the American nation traveled, lived, and worked. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 green-lighted the planets largest public work: the 42,795-mile National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. The nation eagerly embraced its expressways, at least at the start. Nothing is more American than striking out for new horizons, so it seemed only appropriate that America should have the biggest, fastest, safest, most beautiful roads the world had ever seen.

Before the concrete was dry on the new roads, however, a specter began haunting them: the highway killer. He went by many names: the Hitcher, the Freeway Killer, the Interstate Killer, the Killer on the Road, the I-5 Killer, the Beltway Sniper. Some of these criminals were imagined, but many were real. Highway violence followed hard on the heels of interstate construction: America became more violent and more mobile at the same time.

Were they linked? Did highways lead to highway violence? Yes and no. More highways meant more travel, more movement, more anonymityall conducive to criminality. Highway users could become easy victims: stranded motorists, hitchhikers, drifters, and truck stop prostitutes were vulnerable to roving predators. But most killers are not predators, most predators dont roam the country, and highways have never been the main stage for the nations bad actors. In the cultural unconscious, however, highways and violence quickly became entwined. Jim Morrison sang about a killer hitchhiker; slasher films dispatched hitchers by the score; Steven Spielbergs first feature film, Duel, centered on a faceless, murderous trucker. Add a steady stream of news stories about snipers on overpasses, snatchers at rest stops, drive-by shooters, drivers with road rage, and the conclusion is clear: the highway is full of dangers! If a song or book title contains the word Interstate or Freeway, expect mayhem, or at least some road-related bloodshed. If youre watching a movie in which the family car breaks down on the highwayextra points if its in the rain, at nightyou know what to think: Dont get out of the car! Theres a psychokiller on the road.

By the eighties, when the interstate network was completed, it was considered a dangerous placeand not just because of car accidents. People feared hitchhiking, breakdowns, rest areas, truck stops, and aggressive drivers. There was a killer on the road all right, and regardless of how real he was, he had a choke hold on the American imagination. Today the highway killer, like the train robber, the gangster, and the mobster before him, has entered the cast of American outlaws, and the freeway has taken its place among landscapes that easily lend themselves to nightmares.

The freeway killers rise as a type paralleled the nations increasing disillusionment with its highways. Expressways were originally considered not only safe and speedy, but beautiful: the nations first limited-access divided highway, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, was nicknamed the Dreamway. People lined up for hours to drive on it. In the fifties, new interstates were featured in ads for cars, gasoline, tires, and more. Chevy ads featured a collection of divided highways, asking, Which would you pick as Americas finest road? Its a startling contrast with car ads today, where vehicles glide down winding two-lanes, cruise down beaches, perch on rocky overlooks, bounce over cobblestonesgo anywhere, in short, except down a divided highway.

Today the highways are not only seen as ugly, they are often depicted as downright vicious. The road, writes James Kunstler, is now like television, violent and tawdry. Critic Jane Holtz Kay described the mechanical scythe of the highway that Even when not actively committing murder, the expressway has become a marker of social dysfunction: films from Falling Down to Freeway to Crash propose highways as analogs for cultural psychosis. Moviemakers can simply toss out an image of a freeway packed with cars to suggest a world gone mad. In the opening sequence of James Camerons blockbuster Terminator II, a slow-motion shot of a busy interstate dissolves into a nuclear holocaust. Somehow, the film hints, the highway took us here. Sold to the nation as the safest, fastest, most beautiful route to the best of all possible worlds, our interstates werent here for long before they were recast as highways to hell.

Why should this be? Why should one of our most impressive public works evoke in us feelings of fear and unease? Indeed, a few deranged individuals did use the highway system, and the anonymous landscapes it created, as a means to murder. But the response to those crimes went well beyond their actual danger to the population. The disproportionate fear of the killer on the road reveals cultural misgivings about highways and the values they represent.

Next page

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).