Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

C ONTENTS

to Rene

I NTRODUCTION

For fifteen years it was my job to think about the natural world, and about human relationships with that world, in a way that would interest the 500,000 readers of a certain magazine. Most of those readers were people who neither knew nor cared much about the difference between a barnacle and a limpet, the difference between a meadow and a savanna, the difference between an ecosystem and the environment (that vague, misguided locution), or the difference between Henry Thoreau the man and Henry David Thoreau the literary icon. The magazine was Outside , an admirable publication dedicated largely to travel, adventure, and outdoor sports such as climbing, kayaking, bicycling, ski mountaineering, triathlon, sailing, spelunking, scuba diving, parachuting off tall buildings, Rollerblading through tough neighborhoods, and grappling catfish bare-handed out of Louisiana bayous. I was one of its columnists, charged with filling a space each month with an essay of roughly three thousand words that dealt, at least tenuously, with science or nature.

The column was called Natural Acts. It had been conceived under that title by the magazines founding editors and written for the first four years (1977 to 1981) by an able essayist named Janet Hopson. I took over in mid-1981, putting my own voice, perspective, and set of concerns into it for the next decade and a half. When I accepted the invitation to begin writing this column, I thought I might have ideas and energy enough to carry through one or two years. But the ideas kept coming, and the time flew.

During that period, the saintly editors of Outside (notably John Rasmus, Mark Bryant, David Schonauer, and Greg Cliburn) allowed me unimaginable freedom to explore a wide range of peculiar theories, remote places, bizarre facts, and unpopular opinions, and to depart distantly from conventional nature writing, of which I have never much cared to be either a reader or an author. The editors, for their part, didnt want conventional nature writing eitherno sensitive descriptions of wildflowers or babbling brooks, no sylvan dithyrambs, no hushed piety in the presence of Mr. Woodchuck and Mrs. Deer. They let me monger scandal about the secret life of spoon worms. They let me say tasteless things about bedbugs. They let me digress into history and culture. They let me discuss the latest scientific thinking on monogamy, earthquake prediction, and (these were three separate topics, by the way, not a logical triad) penises. They let me dabble in literary criticism, deliver eulogies when I felt moved to, rant about the end of life as we know it. They let me be silly one month and Jeremiah the next. The only stipulated requirements (well, implicitly stipulated) were that each essay, no matter how aberrant, should contain at least passing mention of an animal, a scientist, or a tree; and that I meet each monthly deadline with something. My first Natural Acts column, a contemplation of the redeeming merits of mosquitoes, titled Sympathy for the Devil, ran in June 1981. My final column, a look at the evolutionary history and minatory significance of city pigeons, titled Superdove on 46th Street, appeared in March 1996. (Neither of those essays is included here, since theyve been reprinted in previous books.) Between the devil and the doves, I produced about 150 other columns. I never got two sneezes ahead of the deadline schedule, and I seldom knew more than a few days in advance what subject I would dive into next. Once a month for fifteen years I became frantic.

For a writer prone to vagrant curiosities, intrigued by verminous creatures, with a hearty appetite for library research (especially in scientific journals) and field research (especially in rainforests, swamps, mountains, and deserts) but not for the sort of telephone research (calling experts for canned quotes, ugh) that too often serves as the staple of science journalism, this column was an ideal gig. It gave me occasion to write some essays that would have been too far beyond the fringe for a freelance journalist selling work piece by piece. It also gave me a strong sense of the sacred, enriching, mutualistic relationship between writer and audience.

I mention that sense of relationship because a column is, in my opinion, different from other sorts of magazine writing. Part of a columnists special task is to turn oneself into an agreeable habit, yet to maintain an edge of surprise and challenge that prevents readers from letting the habit become somnolent rote. One way of doing that is to deliver outlandish material in a friendly, companionable voice. Speak to the readers as though you and they know each otheran illusion that becomes, increasingly over time, true. Although the facts and ideas change drastically from month to month, something remains constant: the relationship. I loved the particular audience to which Outside gave me access. (I still do, so long as I can address those readers at feature length, and no more than several times a year.) But eventually I wanted to break the habit, for the best interests of all concerned. I quit the column after fifteen years because I was tired, very tired, of producing such short essays month after month, and because I didnt want to start repeating or imitating myself.

Now the audience is you. This book is an assortment of some of the more durable (I hope) and closely interrelated pieces I wrote during my latter eight years as a columnist. Unlike the three earlier books that Ive drawn from magazine work Natural Acts (1985), The Flight of the Iguana (1988), and Wild Thoughts from Wild Places (1998)this one consists solely of essays that appeared in the Natural Acts column, with no larding of longer work done for Outside or other magazines. That self-restriction is a matter of choice, not of empty file cabinets. I wanted to make a book that reflects the range and trajectory of notions explored over time by one columnist for one set of readers. Although magazine audiences tend to be much larger than the audience any book (except a best-seller) receives, the relationship between a magazine writer and the readers tends, in most circumstances, to be fleeting and shallow. In a book, on the other hand, a reader undertakes a sustained and serious connection with the writer. And the bond that grows between a columnist and a magazine readership over a period of years, I submit, is more like the situation with a book. Themes recur. Ideas are teased at, tested by time as well as by further delving, advanced in small stages. Hobbyhorses are ridden, stabled, and trotted out again later. Characters reappear. Inevitably the columnist commits small, incremental acts of self-revelation, becoming a character too. If the columnist isnt careful, in fact, he or she might realize after some long run of years that the installments collectively represent not just a manifesto but an autobiography. That too is part of the deal. A column can be the most conversational form of journalism, but to create the sense of a conversation with readers, the writer must consent to be a person, not just a pundit. Good writing sounds like talk, not oratory.

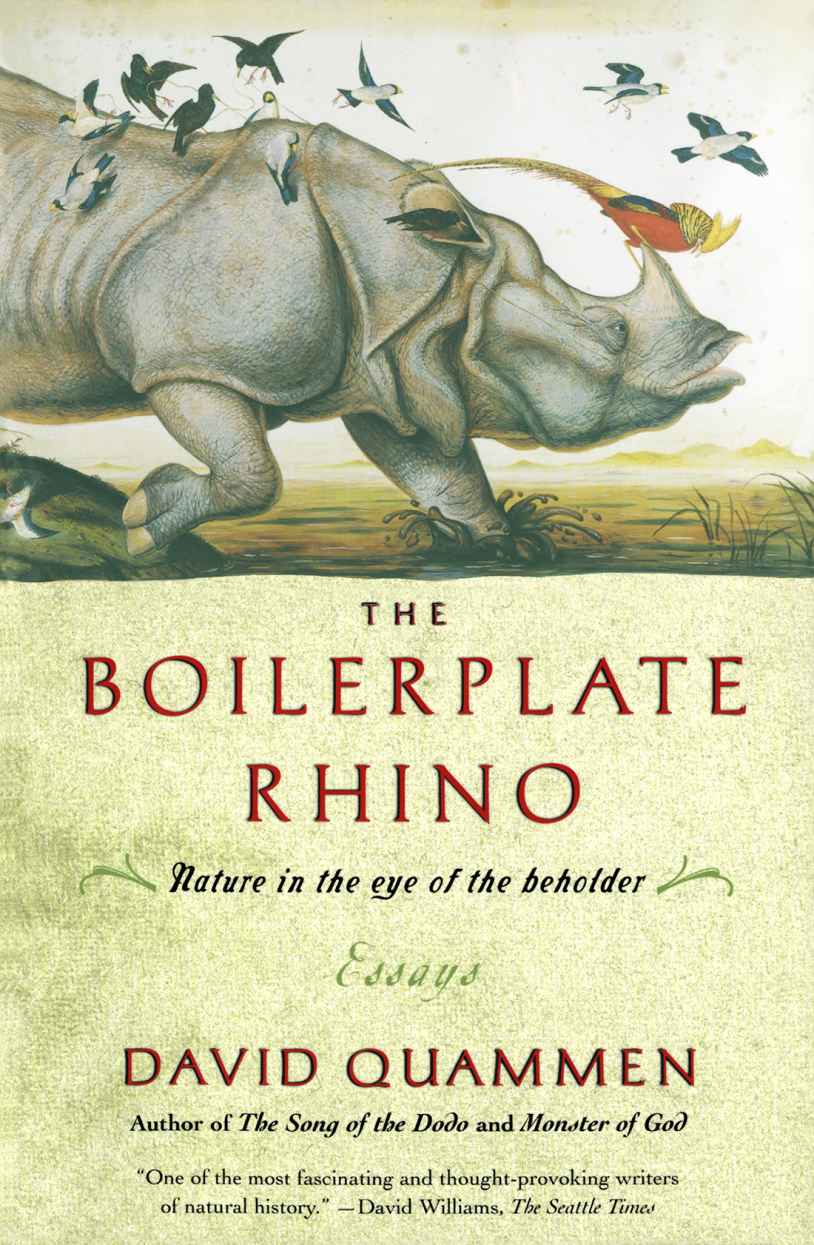

In deciding which essays to include here, I focused on one underpinning theme: How do humans, in all their variousness, regard and react to the natural world, in all its variousness? Hence the discussions of rattlesnake handlers as well as rattlesnakes, of arachnophobia as well as spiders, of fruit-bat chowder as well as fruit-bat conservation, of trilobite photography raised to an art form, of Gods and Tom Lovejoys fondness for beetles, and of the famous rhinoceros that Albrecht Drer knew only by hearsay. Hence also the books subtitle, Nature in the Eye of the Beholder. This focus on human perceptions and attitudes isnt airily epistemological, nor is it a cynical concession to the narcissism of audience. Its what interests meand, I hope, you. Even a part-time misanthrope like myself has to admit that, of all the weird species that inhabit this planet, few are more richly and horrifically fascinating than Homo sapiens. Although I believe that humanity collectively represents a ruinous ecological outbreak population of unprecedented puissance, I would never deny that as individuals we live out some compelling stories. Shakespeare said it diplomatically: What a piece of work.