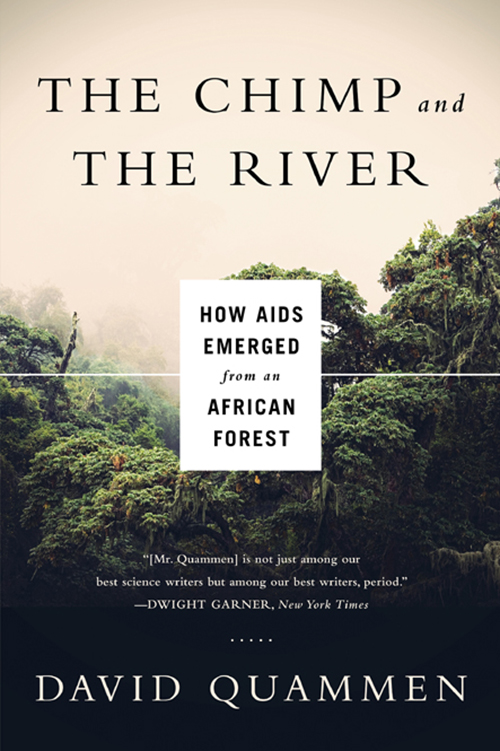

THE

CHIMP

AND THE

RIVER

How AIDS Emerged

from an African Forest

DAVID QUAMMEN

W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

Copyright 2015, 2012 by David Quammen

Extracted from Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, updated and with additional material.

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Iris Weinstein

Production manager: Louise Parasmo

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Quammen, David, 1948-, author.

The chimp and the river : how AIDS emerged from an African

forest / David Quammen.

p. ; cm.

Extracted from Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human

Pandemic, updated and with additional material.supplied by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-35084-5 (pbk.)

I. Quammen, David, 1948 . Spillover : animal infections and the next human

pandemic. Based on (work): II. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Acquired Immunodeficiency SyndromeetiologyPopular Works.

2. HIVpathogenicityPopular Works. 3. ZoonosesPopular Works. WC 503.3]

QR201.A37

614.599392dc23

2014042399

ISBN 978-0-393-35085-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To the men and women who have suffered this disease and those who continue to suffer it

CONTENTS

Although The Chimp and the River focuses primarily on the ecological origins of HIV, and on the scientific work done to trace those origins, the scope of the human catastrophe that is the AIDS pandemic must be noted again, first and foremost, even here in a brief note to record literary debts. We all stand chastened, grieved, and diminished by the miseries and losses that have been suffered by our fellow men and women, as well as awed by and grateful for the courage, determination, and heart of those who have fought against this catastrophe in so many ways.

As noted above, a number of busy scientists gave their generous cooperation to my research toward this book, by sitting for interviews or responding to e-mail or telephone questions: Robert Gallo, Jane Goodall, Beatrice Hahn, Jean-Marie Kabongo, Phyllis Kanki, Brandon Keele, Elizabeth Lonsdorf, Martin Muller, J. J. Muyembe, Martine Peeters, Jane Raphael, Dirk Teuwen, Karen Terio, and Michael Worobey. Most of those people, in addition, did me the vital favor of reading and correcting draft pages. Three other scientists, whose work does not directly involve AIDS, also read this book in its original form (as a long chapter of Spillover) and offered keen editorial advice: Charlie Calisher, Mike Gilpin, and Jens Kuhn. Im deeply grateful to them all.

My gratitude extends also to Patrick Atimnedi, Anton Collins, Zacharie Dongmo, Ofir Drori, Mike Fay, Barbara Fruth, Shadrack Kamenya, Iddi Lipende, Julius Lutwama, Pegue Manga, Neville Mbah, Apollonaire Mbala, Achile Mengamenya, Jean Vivien Mombouli, Albert Munga, Max Mviri, Hanson Njiforti, Mose Tchuialeu, and Lee White, all of whom assisted my inquiries about HIVs origins in Africa. There were others who helped in many ways during the broader effort of researching Spillover (including my editors and other colleagues at National Geographic, among whom that larger project had its beginning), and though their fields of expertise or activity lay outside the immediate frame of the HIV/AIDS story, they contributed much toward allowing me to place that story within its appropriate context: as the most consequential of all modern instances of zoonotic disease. I thanked them by name in Spillover, and I thank them again collectively here.

My other signal debts of gratitude are to Maria Guarnaschelli, my longtime editor at W. W. Norton, who gave her keen eye, her astute judgment, and her literary passion to this book as well as a half dozen others weve collaborated on over the past twenty-five years; and to Amanda Urban, my wonderfully ferocious and smart agent at ICM. Many other people at Norton and ICM have also contributed to this project, and I very much appreciate their work. Rene Golden, Binky Urbans predecessor in my professional life, helped me for decades along the route that led toward this sort of project. Gloria Thiede, faithful Gloria, transcribed all the interviews quoted here. Emily Krieger combined assiduous research with a readers sense of flow, both crucial, in serving as my fact-checker. Daphne Gillam drew the artful, human-handed map. My amazing wife Betsy was always nearby to listen, to read, to discuss, to counsel, and to hold the family together, even while fulfilling her own professional duties. Harry, Nick, Stella, Oscar: Thanks for all you give. Ive been blessed with an extraordinary network of colleagues, sources, professional partners, friends, and loved ones, and Im quite aware that the work couldnt happen without them.

A IDS has been written about many times, from many angles, but the story as told here is drastically different from any version you are likely to have read, heard about, or otherwise absorbed. The main difference is that this is an account of the ultimate source of the pandemic. Its essentially an ecological narrative rather than a medical oneby which I mean that it turns on the interaction of three kinds of creature: chimpanzee, human, and virus. I have tried to describe how, when, and where the virus in question (HIV-1 group M, the pandemic strain), which was previously unknown among people, got its start in the human population. There was a single point in space and time. There was a fateful event. The world became cognizant of AIDS in the early 1980s, of course, but that wasnt the beginningfar from it. The real moment of origin occurred decades earlier and thousands of miles away. Its now possible to say, based on persuasive research in molecular genetics, as published in scientific journals but little noticed by the public, that the virus passed from a single chimpanzee into a single person, during a presumably bloody encounter, in the southeastern corner of Cameroon, near a minor tributary of the Congo River, around 1908, give or take a margin of error. Key components of that research were led by Beatrice Hahn, then of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Michael Worobey, at the University of Arizona, both of whom feature in this little book.

In The Chimp and the River I trace backward to that moment of origin, reconstruct it, and then follow its consequences forward again, along the pathways of social history, epidemiology, and dolorous accident, to the point when AIDS suddenly emerged as a global human disaster.

AIDS is horrible and unique, but its also part of a larger pattern. Everything comes from somewhere, and strange new infectious diseases, emerging abruptly among humans, come mostly from nonhuman animals. The disease might be caused by a virus, or a bacterium, or a protozoan, or some other form of dangerous bug. That bug might live inconspicuously in a kind of rodent, or a bat, or a bird, or a monkey, or an ape. Crossing by happenstance from its animal hideaway into its first human victim, it might find surprisingly hospitable conditions; it might replicate aggressively and abundantly; it might cause illness, even death; and in the meantime, it might pass onward from its first human victim into others. Theres a fancy term for this phenomenon, used by scientists who study infectious diseases from an ecological perspective:

Next page