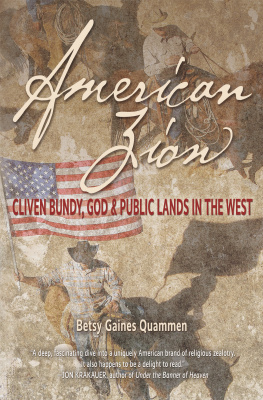

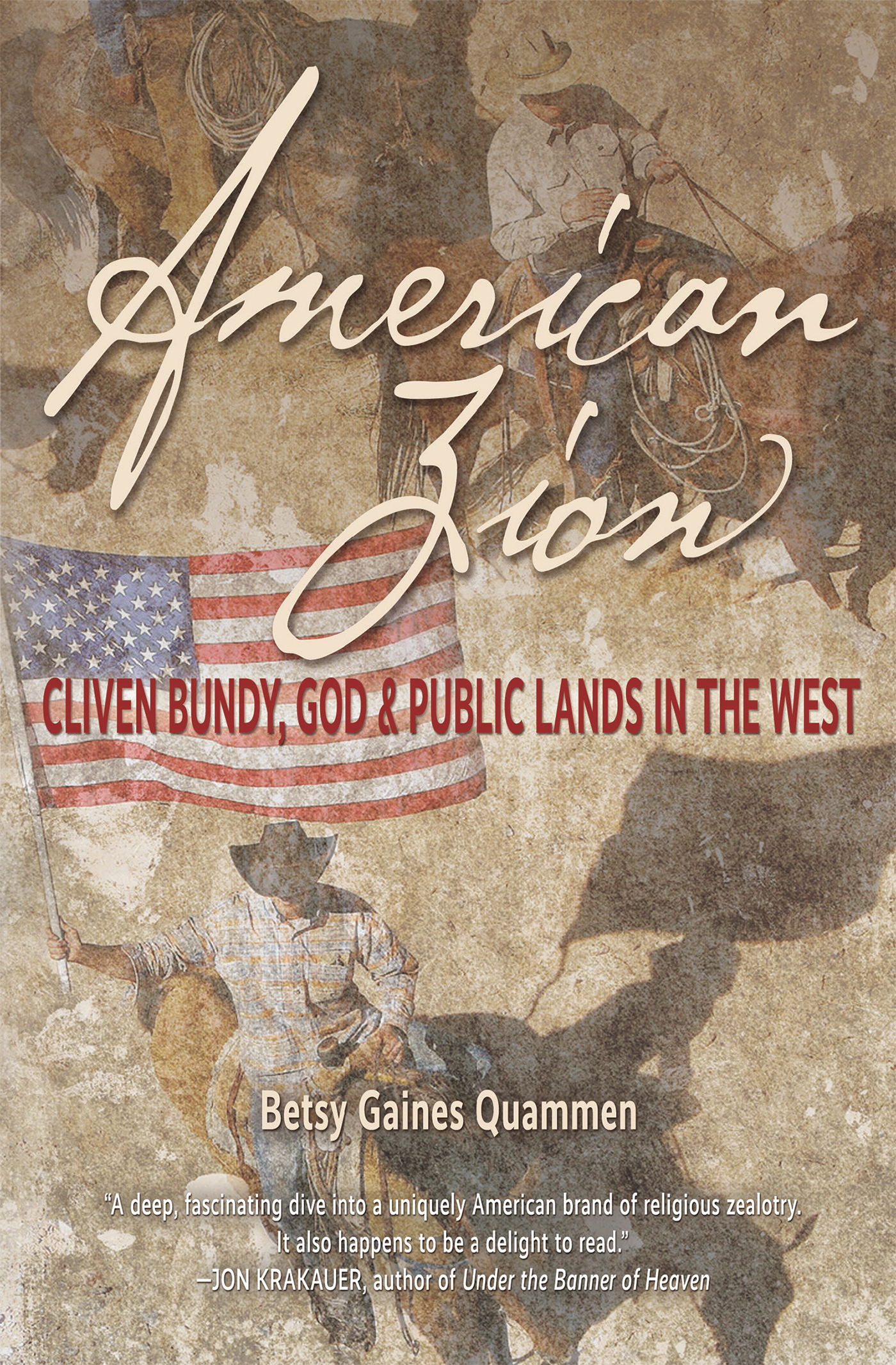

Praise for American Zion

A deep, fascinating dive into a uniquely American brand of religious zealotry that poses a grave threat to our national parks, wilderness areas, wildlife sanctuaries, and other public lands. American Zion provides essential background for anyone concerned about the future of open space in the western United States. It also happens to be a delight to read.

JON KRAKAUER, author of Under the Banner of Heaven

Brilliant and electrifying Gaines Quammens voice is bright, engaging, and smart. She listens. She is fair. But she is not seduced by cowboy mythology. Her vision calls for an ecological wisdom that can govern our communities, both human and wild, with reverence and respect.

TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS, author of Erosion

A fascinating primer on the twisted and nefarious legacy of theology, entitlement, conquest, and patriarchy in the American West.

FLORENCE WILLIAMS, author of The Nature Fix

Betsy Gaines Quammen has accomplished something I thought impossible: combining a rich historical account of the Mormon push west and the accompanying conception of Zion with cleareyed reporting on the Bundys. This book is like a skeleton key, unlocking so many complicated, and largely unquestioned, myths of the West.

ANNE HELEN PETERSEN, BuzzFeed News

A creative, deeply thoughtful work on the origins, dynamics, and consequences of the Bundy legacy.

JEDEDIAH ROGERS, author of Roads in the Wilderness

I find the authors sense of the tribal perspectives spot on and sensitive. I enjoyed American Zion immenselyBetsy is a great storyteller!

WALTER FLEMING, department head and professor of Native American Studies, Montana State University

What J. D. Vance did with Hillbilly Elegy to explain small-town Appalachian angst, Gaines Quammen has done with American Zion to help people understand the long and convoluted issues in the American West.

THANE MAYNARD, co-author with Jane Goodall of Hope for Animals and Their World

Historian Betsy Gaines Quammen recounts the history of Mormons in America to help us understand how a painful abyss has formed between some of that religions believers and management of national public lands. Such understanding is essential for those of us working to cross that divide.

MARY OBRIEN, author of Making Better Environmental Decisions

A thorough and thoughtful analysis of the challenges we face in managing our public lands and an argument for why these lands should remain in public hands.

JAMES LYONS, former deputy assistant secretary, US Department of the Interior

An empathetic and clear-eyed account of the intersections of faith, conservation, and Native rights in the skirmishes over western public lands.

ANDREA AVANTAGGIO, Marias Bookshop

Well-researched and compelling Gaines Quammen is a natural storyteller.

ARIANA PALIOBAGIS, Country Bookshelf

American Zion

American Zion

Cliven Bundy, God & Public Lands in the West

Betsy Gaines Quammen

TORREY HOUSE PRESS

SALT LAKE CITY TORREY

First Torrey House Press Edition, March 2020

Copyright 2019 by Betsy Gaines Quammen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written consent of the publisher.

Published by Torrey House Press

Salt Lake City, Utah

www.torreyhouse.org

International Standard Book Number: 978-1-948814-14-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-948814-15-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019936116

Cover photo Members of the Bundy family and their supporters near Bunkerville, NV, in April 2014 by Jason Bean, Las Vegas Review-Journal

Cover design by Kathleen Metcalf

Interior design by Rachel Davis

Distributed to the trade by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

This book is dedicated to my two big Ds, David and Dad

CONTENTS

Introduction

A map of the American West is a Rorschach testpeople see what they want to see as reflections of who they are. There are those who see land solely for human utility. And those who see a realm for wild creatures. Some see the West as a place of colonialization and genocide, where the indomitable mettle of Indigenous peoples nevertheless endures. Some see a land of plunder, evidenced by slag heaps, old mining pits, and the abandoned equipment of long-ago endeavors. There are empty corners where a look in any direction reveals no obvious human marks, though the marks exist. This is a land heavily trod. Dying towns punctuate the old highways, their Main Streets marred by boarded-up windows, their schools emptied by dwindling enrollments. These towns are just miles from robust cities, ballooning with the influx of new residents and tech businesses. The West is a place of a thousand destinationson rivers, on mountains, on prairies, and on rocks. Its where cars speed down lonely roads, flanked by grazing horses and cattle, fence lines and range, billboards and baled hay. It is a place of differing points of view, a place of intersections and of loggerheads. People see their own ink blots here, spread across a land colored by custom, ambition, opportunity, and cowssacred and otherwise.

The Intermountain West, a region of such differing interpretations, is geographically delimited by the Rocky Mountains to the east, the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Ranges to the west, and encompasses the Columbia Plateau, the westward drainages of the Northern and Southern Rockies, the Great Basin and the Mojave Desert. On the map, it is a large jumble of boundaries and ownerships with checkerboard designations and varying jurisdictions, sometimes running across state lines. A cartographic color code and a series of demarcations make one thing crystal clear: most of the Intermountain West is federal public land. Which means that all Americans, as citizens and taxpayers, are proprietors of some of the most incredible real estate on this planet. The best part of the West is that we share itin all its fraught majesty. And this affords opportunity for further insights into how this land is variously construed. Somewhere between 280 and 560 generations of Indigenous people have been young and grown old here on the western landscape. Today, 327 million Americans participate in its proprietorship.

Public lands are precious and beloved places to westerners and non-westerners alike. They are finite and fragile, and have very real thresholds of tolerance to ruination. And theres the rub. Some people are asking too much of these lands and, in doing so, are declaring war both on nature and on the millions of people who also share public lands. This is nothing new. The West has always been a place of competing cultures and priorities that began with cultural and resource conflicts among Indigenous nations. As Europeans arrived and homesteaded, their claims to these lands were devastating for Native peoples. Not long after settlement slowed and the western frontier was closed, a battle between preservationists, timber barons, and ranchers spurred the creation of national parks and monuments and set the match to land wars that still burn today. Mining companies, four-wheel-drive enthusiasts, and those in livestock production have wrestled for control over lands that wildlife need and conservationists fight to protect. It falls to the American public to decide how these lands should be understood and managed. Should these lands be a place for recreation or for industry? For carbon sequestration or for resource extraction? For short-term gain or long-term viability? For everyone or a few individuals? To repeat the obvious: these lands belong to all Americans, yet their use is being determined by a limited number of politicians and rogue players.

Next page