Contents

Page List

Guide

PRAISE FOR STANDOFF

Eye-opening and compelling required reading for those who would call this land home.

KIRKUS REVIEWS

Standoff has the potential to launch a trend of orderly and pertinent analysis of the societal, cultural and structural issues that provide the context within which todays Indian Movement(s) operate and presents a challenge to Indian people whether we continue to play the game of accepting our place in America or define who we are and what we want to be.

SAM DELORIA, law professor emeritus, University of New Mexico

Environmental activists, Indigenous rights activists, and allies should take note of the challenging, unjust, and at times beautiful accounts shared here, which illuminate the complexity of what it means to stand in solidarity in a colonial state.

MARISA ELENA DUARTE, assistant professor, Arizona State University School of Social Transformation

This is the kind of book we owe to young Indigenous kids. They deserve the truth, even if it hurts, and this brave, well-sourced journalism deserves to be named for what it will go down in history as: perhaps the most in-depth look at the #NoDAPL movement, coming from where it should: your nation and from within Indian country.

DESIREE KANE, journalist

Jacqueline Keeler weaves personal experience, cultural awareness, and journalistic acumen to tell a compelling story that compares and contrasts two modern and historic Western encounters between federal land policy and the people who inhabit these lands. Whose land is it anyway? Keeler ultimately asks, and finding the answer is a task that requires deep reflection from all of us who share these magnificent vistas.

CHRIS LA TRAY, author of Becoming Little Shell

Jacqueline Keeler, a master storyteller and reporter, crafts a knotty skein, twining together family traditions, Native and colonial histories, personal experiences, and crackerjack journalism. Standoff explores inequity and entitlement, seeking answers to what American land means to cultures with divergent values and uneven advantages.

BETSY GAINES QUAMMEN, author of American Zion

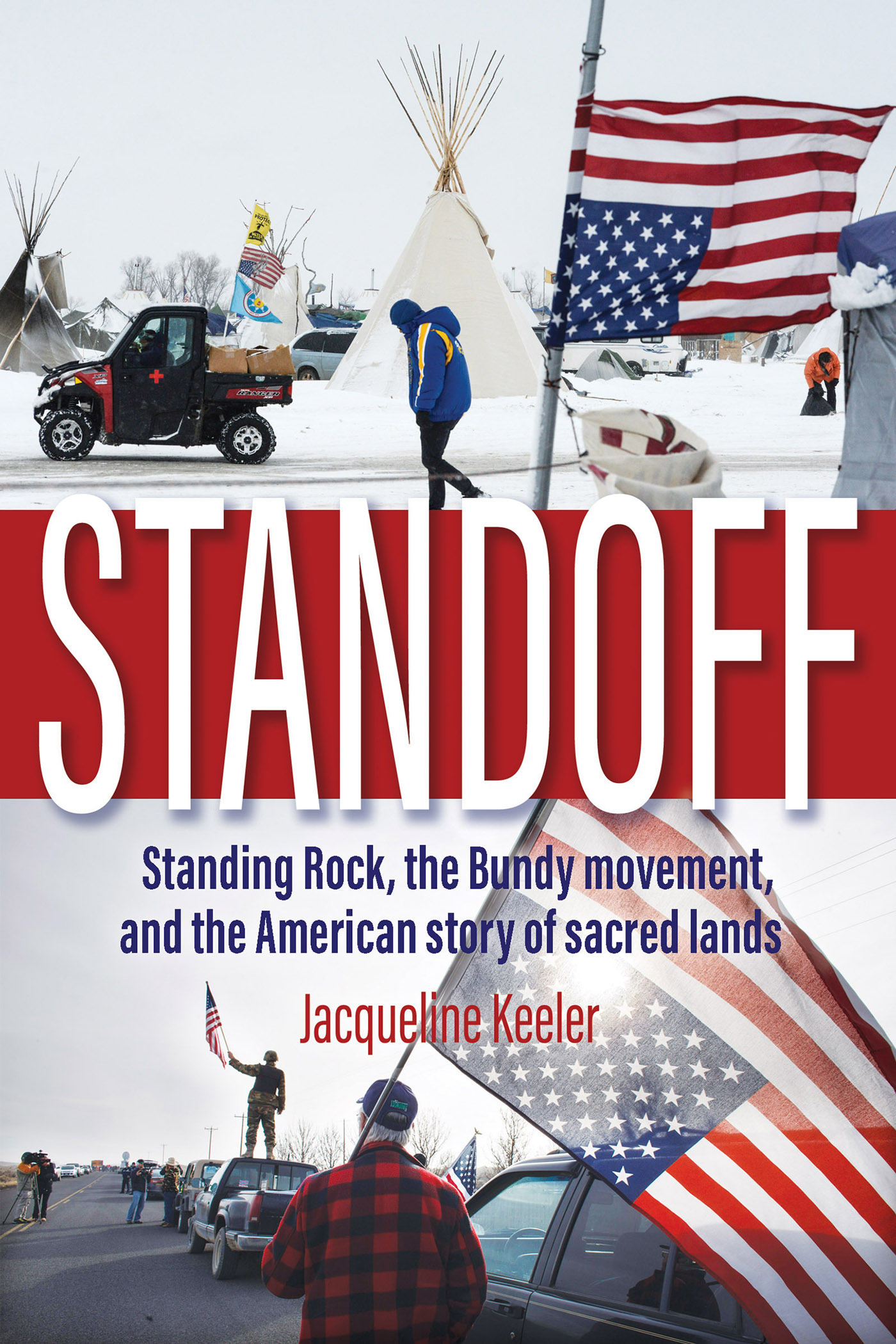

STANDOFF

STANDOFF

Standing Rock, the Bundy Movement, and the American Story of Sacred Lands

JACQUELINE KEELER

TORREY HOUSE PRESS

Salt Lake City Torrey

First Torrey House Press Edition, March 2021

Copyright 2021 by Jacqueline Keeler

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written consent of the publisher.

Published by Torrey House Press

Salt Lake City, Utah

www.torreyhouse.org

International Standard Book Number: 978-1-948814-27-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-948814-50-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017947293

Cover photos by Stephanie Keith/REUTERS and Rob Kerr/AFP via Getty Images

Cover design by Kathleen Metcalf

Interior design by Rachel Buck-Cockayne

Distributed to the trade by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

Torrey House Press offices in Salt Lake City sit on the homelands of Ute, Goshute, Shoshone, and Paiute nations. Offices in Torrey are in homelands of Paiute, Ute, and Navajo nations.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A young man holds a staff on a gray asphalt road surrounded by the prairie. Its October and the grass has turned gold and dry. The bent staff is decorated with eagle feathers. The youth, Danny Grassrope of the Kul Wicasa Oyate (Lower Brule Sioux Tribe), is wearing a red scarf over his head and beige pants and a T-shirt. The men wrestling with him and the staff are mostly in black uniforms, some in green jackets and beige polyester pants, most wearing riot gear helmets, a few wearing respirators, and all carrying guns in their holsters. His slight figure goes down, but still he hangs on to the staff. In the end, the law enforcement in riot gear take it and pin him down, pressing his face to the soft earth, and lashing his wrists behind his back with plastic handcuffs.

The Lakota youth that had begun the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) had carried that staff across the countryfrom North Dakota to Washington, DC. They had run thousands of miles to request that the Army Corps of Engineers reconsider allowing the crude oil pipeline to be built just a mile north of the sole intake source of water for their reservation. The young man was not just fighting for an object, but for a symbol of that prayerthat prayer a new generation was carrying for the future.

The staff and other personal items like sacred pipes, canunpa, were later returned to the main Octi Sakwin (Sioux) camp north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. They came in plastic bags with numbers on them matching the numbers that were written on their owners arms in jail. Elders I spoke to who held a ceremony to bless and cleanse them told me they smelled of urine and had evidently been peed on.

How did American citizens end up on either side of this standoff? The police in the armor and the young man armed only with a staff representing the prayers of his people?

The scenes of the raid of the 1851 Treaty Camp near the Dakota Access Pipeline construction corridor on October 28, 2016, did not resemble the post-racial America Obamas administration was supposed to usher inan America where the lessons of the civil rights movement had been fully integrated into the power structure of the nation by the election of a Black man as leader of the free world.

Instead, Obamas administration oversaw the violent arrest of 142 water protectors that day. Images of the forcible removal of the camp are haunting. Tipis ripped open by white men in military uniforms. Native people being dragged out of a sweat lodge. A Native youth leader fighting to keep a medicine staff from the police. These scenes are reminiscent of the 1863 Whitestone Massacre that occurred not far from the 1851 Treaty Camp.

Just nine months earlier, along another state highway, LaVoy Finicum, an Arizona foster parent, is run off the road by a blockade set up by the Oregon State Police to capture the leaders of the armed takeover of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. On the snowy roadside, surrounded by police cars, he gets out of a white SUV with his hands up. He speaks imperiously to the police, giving the impression he expects to be able to have a conversation as equals with them. In the month the armed occupiers, led by Ammon Bundy, son of scoff-law Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, have held the wildlife refuge, they have enjoyed a respectful, if oppositional, relationship with the local county sheriff. They have been free to come and go from the refuge to get supplies or attend speaking engagements like the one they are heading to now: a meeting with the sheriff in the next county and a crowd of about a hundred locals. Finicum obviously felt he had the standing to have a talk with those who had guns pointed at him.

During an earlier media interview, when asked why he was sitting with a rifle draped across his lap at the refuge, he had said, If you point a gun at me you know what to expect.

Now, with police guns pointed at him, he walks across the snow and reaches a few times toward a pocket in his denim jacket. Police later allege he had a gun tucked there. The third time he reaches, he is gunned down, becoming a martyr to the cause of public lands detractors.