Contents

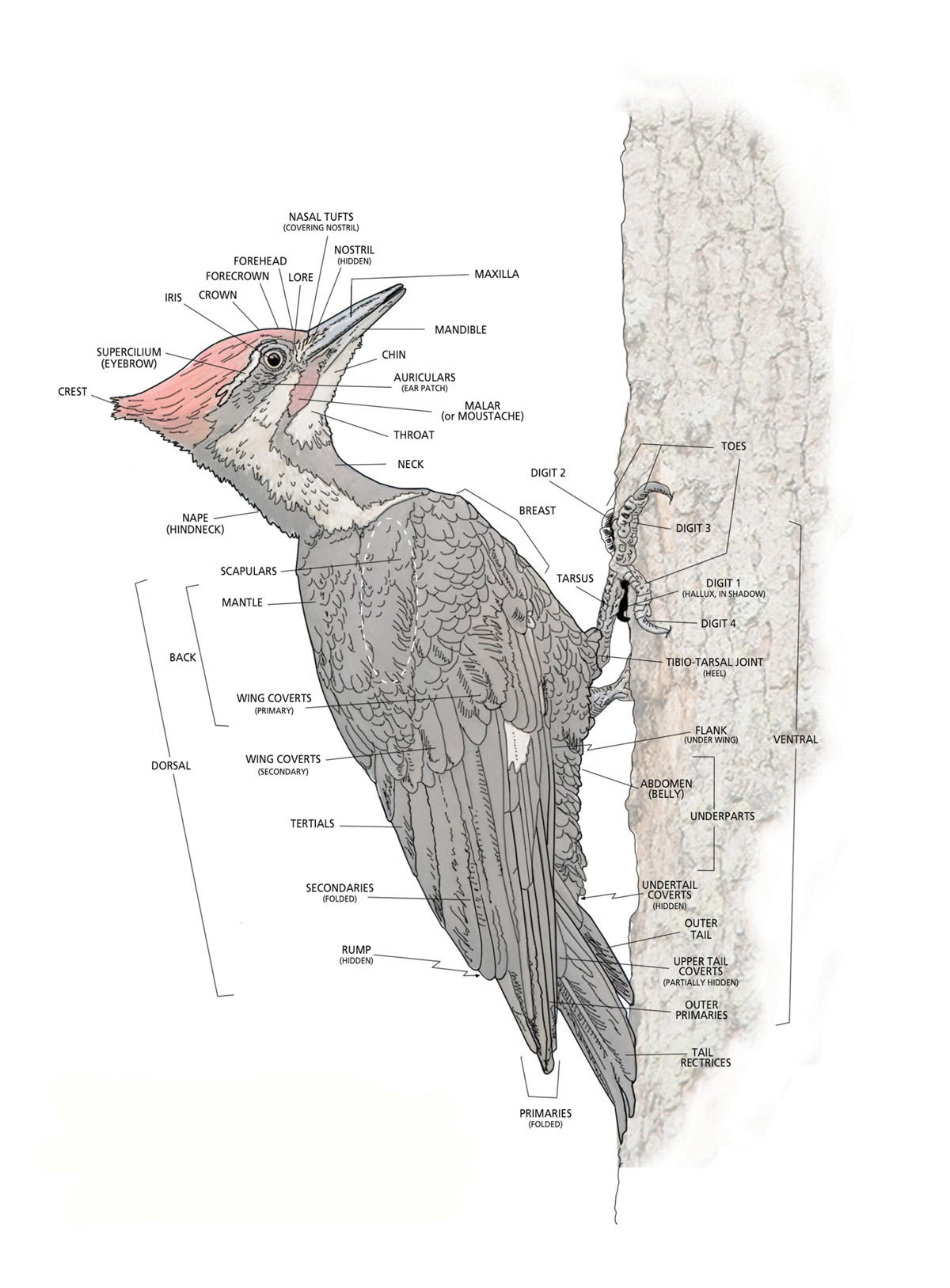

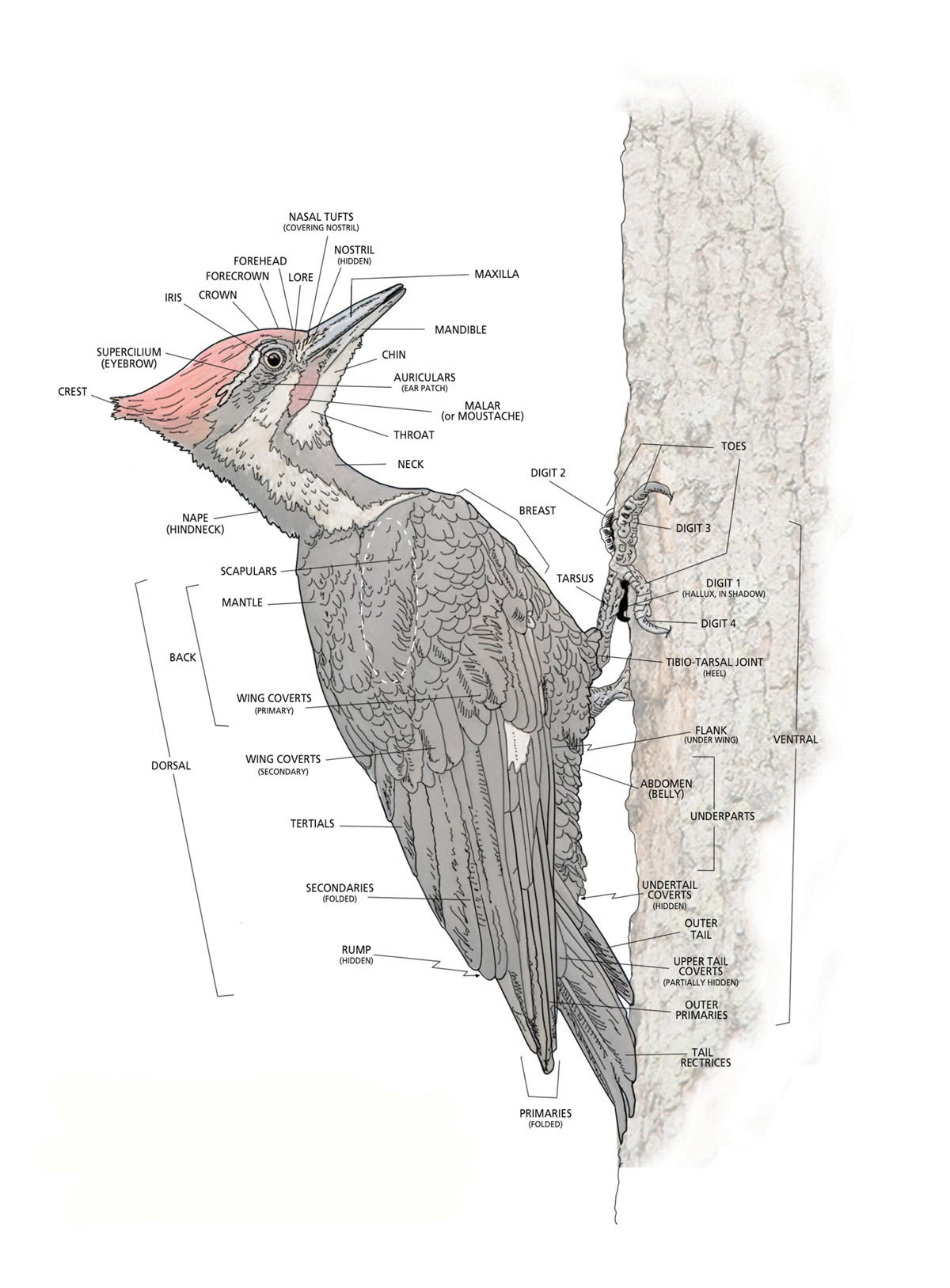

ANATOMY AND ADAPTATION

For centuries, the anatomy of woodpeckers has captivated naturalists and scientists alike (see ). From seventeenth-century comparative anatomy to modern-day research to develop safer football and motorcycle helmets, woodpeckers have been the subject of a broad range of studies examining their anatomical adaptations for their specialized lifestyles.

THE TONGUE AND THE HYOID APPARATUS

Woodpeckers possess a tongue and supporting hyoid apparatus that are perfectly adapted for each species primary feeding behaviors. Variably extensible and subtly diverse, the fleshy tongue is operated by a system of bones and muscles that allows the bird to effectively gather its favored forage.

The Northern Flicker, for example, can extend its tongue 2 inches (5.1 cm) or more beyond the bill tip, allowing it to probe into the deep tunnels of underground ant dwellings. The sapsuckers, by contrast, possess a tongue only long enough to penetrate the deepest sap wells, a mere to inch (12 cm) into the tree. Regardless of their lengths, all woodpecker tongues have the same basic anatomical structure and operate in the same manner.

The Extensible Tongue

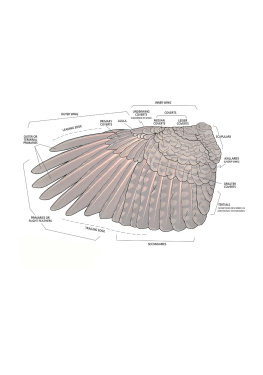

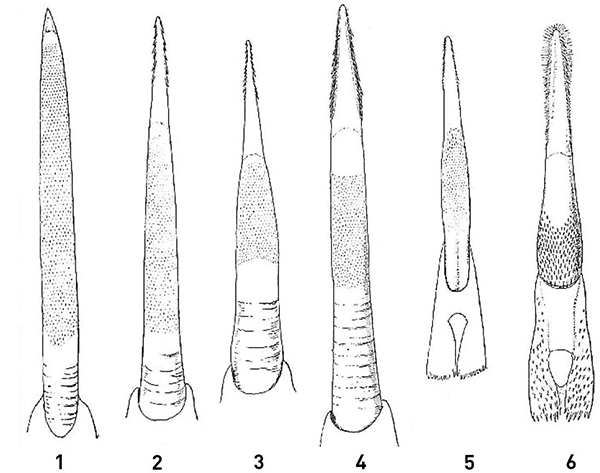

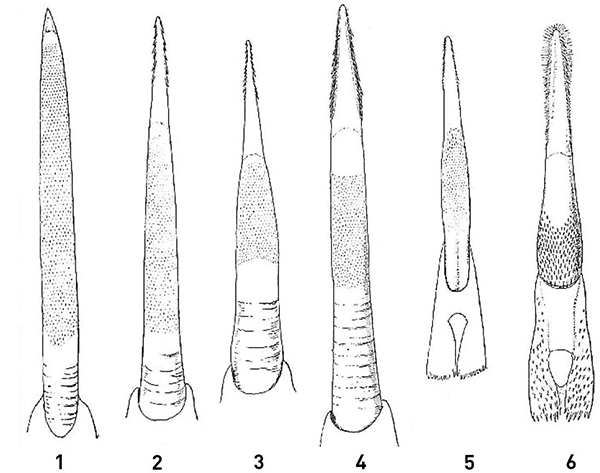

The fleshy part of the woodpecker tongue shows three distinct sections: the base, center, and tip. The base is covered with a smooth sheath of skin that accordions when the tongue is retracted. The center appears as rough, rubbery skin to the naked eye, but a microscope reveals this roughness to be tiny backward-pointing granules, decreasing in size from the base of the tongue toward the tip. The character of these granulesespecially the extent, number, and sizevaries widely among species (see ).

The greatest variability in woodpecker tongues is right at the tip, which is stiff and hornlike with variable barbs, most of which angle back toward the base. These barbs may resemble sharp spines, and they number from just a few in the flickers to dozens in the Red-headed Woodpecker. In the sapsuckers, they resemble fine hairs, some directed outward from the surface and some angled backward. These barbs are particularly well developed on the tongues of the most specialized excavatorsthe Black-backed and American Three-toed Woodpeckersallowing individuals to slide their tongue tip between a grub and its gallery wall and then to hook the grub upon retraction. In adult woodpeckers, the barbs wear with use and constantly regrow. Fledgling woodpeckers have nearly smooth tongue tips.

The Northern Flicker possesses the most extensible tongue of all North American woodpeckers, and the species conspicuous presence affords observation of its extended tongue in a variety of circumstances. Paul Bannick; Dec. 2008, Seattle, WA.

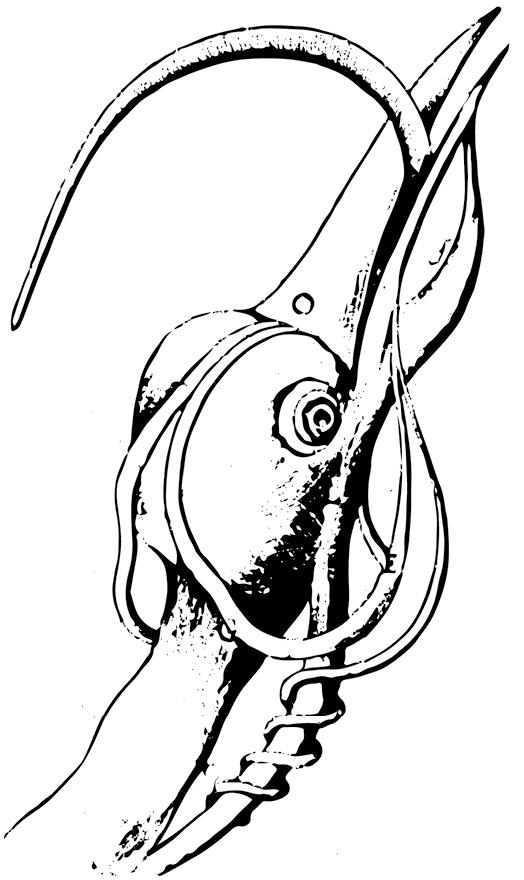

FIGURE 1. Borellis Tongue. The first known drawing of the woodpecker tongue came from Giovanni Alfonso Borelli in his 1680 text De Motu Animalium , or On the Motion of Animals . Here Borelli depicts one of the extensor muscles wrapping around the trachea, which is not the case in all woodpeckers. Borelli 1680.

To assist in prey retraction, woodpeckers possess a larger submaxillary salivary gland than most birds. This gland is largest in the flickers, reaching from the base of the skull into the lower mandible and coating the entire tongue with sticky mucus on its way out of the bill. As the flicker extends its tongue into an ant burrow, this mucus effectively glues ants to the flickers tongue along most of its length. In species with more heavily barbed tongues, the mucus may be concentrated along the bumpy center of the tongue, enhancing the stickiness of this section but allowing the tongue tip the flexibility to seek and secure prey without getting stuck.

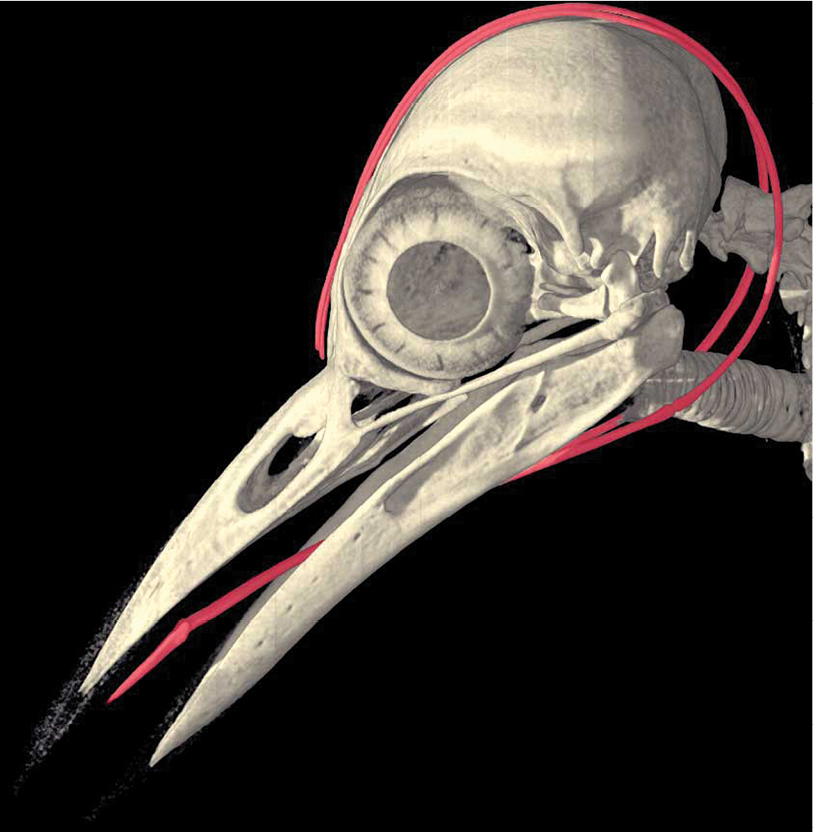

The Hyoid Apparatus

The hyoid apparatus comprises two sets of narrow bones, the medial and the paired hyoids. If the whole apparatus were laid flat, the medial bones and fleshy tongue would form the stem of a narrow, elongated Y. The paired hyoids, known as the hyoid horns, would form the flared part of the Y (see ). In those species with especially long hyoids, such as the flickers, the epibranchials extend through the right nasal opening, under the right nostril, or nare, and along the upper mandible nearly to its tip. Sapsuckers possess the shortest hyoids, proportionally equal in length only to those of some passerines. Fledgling woodpeckers have short hyoid horns, which grow rapidly once a bird begins feeding independently.

FIGURE 2. Diversity in Woodpecker Tongues. The tongue of each woodpecker species is specially adapted for its primary food-gathering behaviors. Those depicted here were studied and drawn in 1895 by Frederic Lucas for the U.S. Department of Agriculture; all are shown at 2.25 times their natural size. (1) Northern Flicker, (2) Hairy Woodpecker, (3) Black-backed Woodpecker, (4) Red-headed Woodpecker, (5) Ladder-backed Woodpecker, (6) Red-naped Sapsucker. Lucas 1895.

In species with bulging frontal bones (see ), the hyoid horns are obstructed from reaching the right nostril, so they curve backward after rounding the front of the right orbit.

The woodpeckers hyoid apparatus requires specialized muscles to render it functional (see ). Woodpeckers lack the specialized tongue retractor muscle, the stylohyoideus, found in other birds. Instead, they have two pairs of muscles: the protracting geniohyoideus and the retracting ceratotrachealis.

The paired geniohyoideus muscles completely encase the hyoid horns, which themselves comprise the ceratobranchial and the epibranchial bones. In the flickers, these muscles and the encased bones may dip downward along the trachea a short distance from the base of the skull before curving up and over the cranium.

FIGURE 3. Retracted Hyoid Position. This high-resolution X-ray computed tomography (CT) scan highlights the in situ position of the hyoid bones of a Golden-fronted Woodpecker. Digital reconstruction courtesy of DigiMorph.org .

In most birds, the ceratotrachealis originates at the larynx, but this would not fulfill the function of retrieving a woodpeckers long tongue. In some woodpecker species, these retractors may spiral down around the trachea several times. (See .) In others, such as the Pileated Woodpecker, they may simply run parallel along the trachea, attaching about seven rings down from the larynx.

Another muscle uniquely adapted in woodpeckers, the esophagomandibularis (not pictured in Figure 5), connects the front of the esophagus to the upper mandible, pulling the larynx and trachea forward and enhancing the tongues extensibility.