Hero

With Wings Like Eagles

Ike

Journey to a Revolution

Ulysses S. Grant

Marking Time

Horse People

Making the List

Country Matters

Another Life

Man to Man

The Immortals

Curtain

The Fortune

Queenie

Worldly Goods

Charmed Lives

Success

Power Male Chauvinism

BY MARGARET KORDA AND MICHAEL KORDA

Horse Housekeeping

Cat People

For Margaret

The past is never dead. Its not even past.

William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The soul that rises with us, our lifes star,

Hath elsewhere had its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home.

William Wordsworth,

Ode: Intimations of Immortality from

Recollections of Early Childhood

Contents

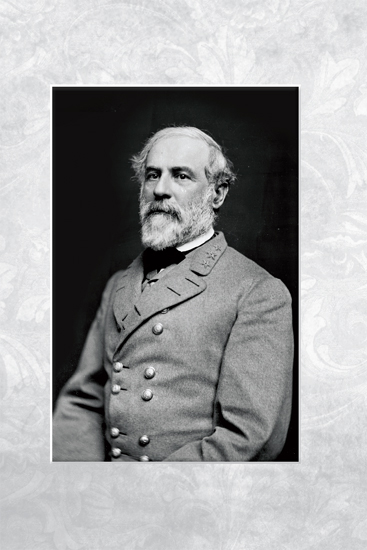

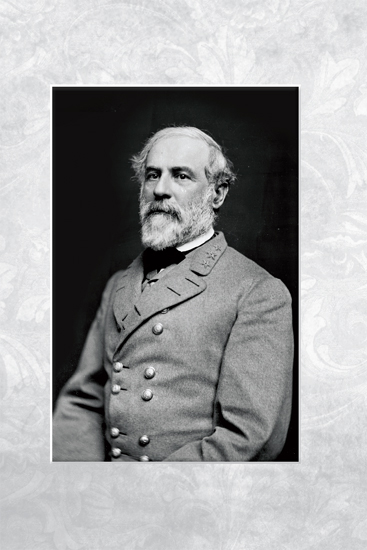

I n October 1859, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee, commanding the Second U.S. Cavalry, in Texas, was home on leave, laboring to untangle the affairs of his late father-in-laws estate. Despite a brilliant military careermany thought him the most capable officer in the U.S. Armyhe was a disappointed man. Nobody understood better than Lee how slowly promotion came in this tiny army, or knew more exactly how many officers were ahead of him in the all-important ranking of seniority and stood between him and the seemingly unreachable step of being made a permanent full colonel. He did not suppose, given his age, which was fifty-two, that he would ever wear a brigadier generals single star, still less that fame and military glory awaited him, and although he was not the complaining type, he often expressed regret that he had chosen the army as a career. An engineer of considerable abilityhe was credited with making the mighty Mississippi navigable, which among other great benefits turned the sleepy town of Saint Louis into a thriving river porthe could have made his fortune had he resigned from the army to become a civil engineer. Instead, he commanded a cavalry regiment hunting renegade Indians in a dusty corner of the Texas frontier, and not very successfully at that, and was now home, in his wifes mansion across the Potomac from Washington, methodically uncovering the debts and the problems of her fathers estate, which seemed likely to plunge the Lees even further into land-poor misery. Indeed, the shamefully run-down state of the Arlington mansion, the discontent of the slaves he and his wife had inherited, and the long neglect of his father-in-laws plantations made it seem only too likely that Lee might have to resign his commission and spend his life as an impoverished country gentleman, trying to put things right for the sake of his wife and children.

He could not have guessed that an event less than seventy miles away was to make him famousand go far toward bringing about what Lee most feared: the division of his country over the smoldering issues of slavery and states rights.

Harpers Ferry, Sunday, October 16, 1859

Shortly after eight oclock at night, having completed his preparations and his prayers, a broad-brimmed hat pulled low over his eyes, his full white beard bristling like that of Moses, the old man led eighteen of his followers, two of them his own sons, down a narrow, rutted, muddy country road toward Harpers Ferry, Virginia. They marched silently in twos behind him as he drove a heavily loaded wagon pulled by one horse.

The members of his army had assembled there during the summer and early autumn, hiding away from possibly inquisitive neighbors and learning how to handle their weapons. John Brown had shipped to the farm a formidable arsenal: 198 Sharps rifles, 200 Maynard revolvers, 31,000 percussion caps, an ample supply of gunpowder, and 950 pikes. The pikes Brown had ordered from a blacksmith in Connecticut two years earliermade to his own design at a dollar apiece, they consisted of a double-edged blade about ten inches long, sharpened at both edges, shaped rather like a large dirk or a broad dagger, and intended to be attached to a six-foot ash pole, a weapon that Brown thought might be more effective and terrifying in the hands of liberated slaves than firearms, with which they were unlikely to be familiar.

Browns reputation as the apostle of the sword of Gideon had been made, for better or for worse, in the widespread guerrilla warfare and anarchy of bleeding Kansas, where pro-slavery freebooters from Missouri clashed repeatedly with Free Soilers, settlers who were vigorously opposed to the extension of slavery into the territory. Southerners were equally determined to prevent a free state on the border of Missouri, which might render this species of propertya current euphemism for slavesinsecure. Violence was widespread and took many forms, from assassination, arson, lynching, skirmishes, and bushwhacking to small battles complete with artillery.

Brown had been responsible for the murder of five pro-slavery settlers at Pottawatomie Creek in revenge for the sacking of the antislavery town of Lawrence, Kansasthey had been dragged from their homes in the middle of the night and butchered with broadswords. Brown led the killers, who included two of his sons, and may have given the coup de grce to one of the victims.

For three years, from 1855 through 1858, a group of Free Soilers under the command of Captain Brown (or Osawatomie Brown, as he was called after his heavily fortified Free Soil settlement) fought pitched battles against Border Ruffians (as the pro-slavery forces were known by their enemies), in one of which his son Frederick was killed. Brown achieved fame bordering on idolatry among abolitionists in the North for his exploits as a guerrilla fighter in Kansas, culminating in a daring raid during the course of which he liberated eleven slaves from their masters in Missouri and, evading pursuit despite a price on his head, transported them all the way to freedom across the border in Canada in midwinter.

John Brown was a man of extraordinary courage and persistence, with a grandiose vision and a remarkable gift for organization. Widowed and remarried, he was the father of twenty children by his two wives; a commanding, often intimidating presence even to his enemies; as much at ease in the elegant drawing rooms of the wealthy New England and New York City abolitionists who supported him as he was in the saddle, armed to the teeth, on the plains of Kansas. He was at once a throwback to the undiluted Calvinism and Puritanism of the first New England settlers and far ahead of his timehowever opposed they might be to slavery, most abolitionists still shied away from social equality with blacks, but Brown had built his home in New Elba, New York, close to Lake Placid, among freed blacks who ate at the same table as the Browns, and whom he punctiliously addressed as Mr. or Mrs. When he redrafted the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution for the benefit of his followers, he included not only racial equality, a revolutionary idea at the time, but what we would now call gender equality, giving women full rights and the vote, promising secure equal rights, privileges, & justice to all; Irrespective of Sex, or Nation. Brave, unshaken by doubt, willing to shed blood unflinchingly and to die for his cause if necessary, Brown was the perfect man to light the tinder of civil war in America, which was just what he intended to do.