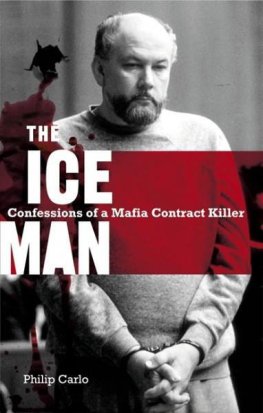

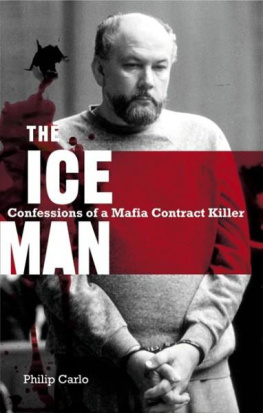

Mug shot of Richard Kuklinski on the day of his capture, 1986.

2013 Bantam Books eBook Edition

Copyright 1993, 2013 by Anthony Bruno

Foreword copyright 2013 by Jim Thebaut

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B ANTAM B OOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover and in slightly different form in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., in 1993, and subsequently in paperback by iUniverse in 2008.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Bruno, Anthony.

The iceman : the true story of a cold-blooded killer / by Anthony Bruno.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-54009-6

1. Kuklinski, Richard. 2. MurderersNew JerseyBiography. 3. Serial murdersNew JerseyCase studies. I. Title.

HV6248.K75B78 1993

364.152309749dc20 92-44003

www.bantamdell.com

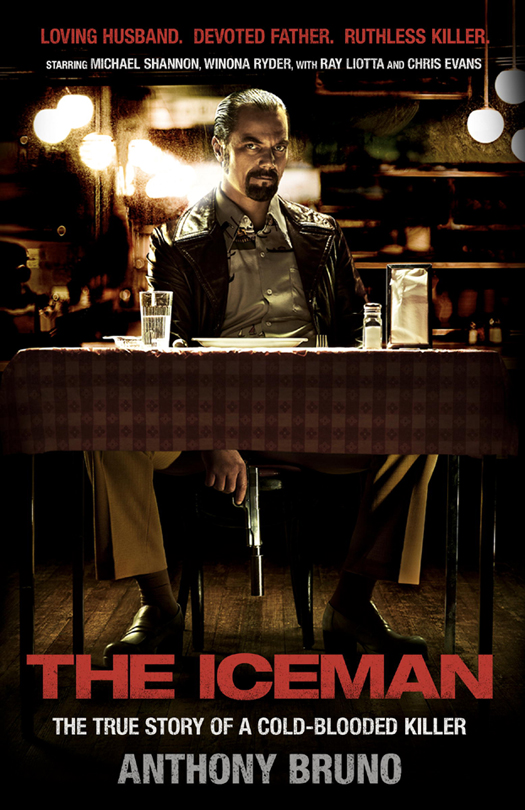

Cover photo Millennium Films

v3.1

Contents

FOREWORD

by Jim Thebaut, producer and filmmaker of The Iceman Tapes

My involvement with the Iceman story started in 1986 when I first learned about Richard Kuklinski, a mass murderer who claimed to have killed scores of people while maintaining an outwardly normal, suburban lifestyle with a wife and three children. The police had nicknamed him the Iceman because he had frozen one of his victims for two years to see if he could disguise the time of death. Clearly this was not a run-of-the-mill killer. I was intrigued, but at the time I had no idea how deeply his story would affect my life. What a long strange trip it has been.

While serving as executive producer on A Deadly Business, a CBS Television dramatic special, a friend and adviser on that project told me that a dangerous killer had just been arrested in New Jersey, and he felt that this mans incredible story would make a great film. A Deadly Business delved into organized crimes involvement in the illegal dumping of toxic waste in the Garden State. The killer, Richard Kuklinski, had been apprehended on the quiet suburban street where he lived. My adviser, who at the time was the director of New Jerseys Organized Crime Task Force and later became a deputy attorney general of the state, told me that Kuklinski would have to be tried before I could approach any of the principal individuals in the case about doing a film, but he would help me get the cooperation of the police and prosecutors. Approximately two years later, in 1988 after Kuklinskis conviction, I started my quest to turn his story into what I hoped would be a powerful and successful motion picture.

What attracted me to this project was the opportunity to explore the dark side of human behavior. Kuklinski claimed to have killed more than 100 people. I wanted to know what created this monster. Was he born this way, or had his upbringing shaped him? I set about to secure the rights to the stories of the people who knew him best: his wife and children, as well as the federal undercover agent who had gotten close to him and secretly taped him talking about his crimes. After several months of negotiation, I was able to obtain options on those rights.

Shortly after, I received a call from the director of the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice, who had prosecuted the case against Kuklinski, asking if I would be interested in interviewing Kuklinski at Trenton State Prison, where he was incarcerated. Naturally I accepted, with the understanding that at a later date I would be allowed to conduct an on-camera interview with him.

My initial meeting with the Iceman lasted two and a half hours. I was first struck by his sizesix-foot-four, well over 250 poundsand immediately recognized how intimidating he must have been on the street. We met one-on-one in a room reserved for lawyer/client conferences. I found him to be straightforward, cordial, and articulate. I felt that his dark story could potentially become a compelling, frightening, and unforgettable documentary, but first I had to see how forthcoming he would be and if he could cinematically sustain a one-hour program. I needed to discover what buttons, if any, I could push to elicit emotional responses on camera. When I asked him about his relationship with his son, he showed deep sadness, and tears came to his eyes. Later on, I realized this line of questioning might show the human being beneath the killer.

The very next day I pitched the idea to executives at HBO. I convinced them that Kuklinski was not just a thug with a gun and a chip on his shoulder. There was a real story here, I told them, an important story. They felt my passion and agreed to move forward with the project.

My first meeting with Kuklinski at the prison laid the groundwork for our on-camera interview, which lasted a total of seventeen hours. In the early spring of 1991 I took a film crew to the prison and, over a three-day period, interviewed Kuklinski for fifteen hours. The prison gave us a room next to the execution chamber, which hadnt been used in fifteen years. Officials from the attorney generals office simultaneously taped the interview for their own use. Their hope was that Kuklinski would provide information regarding unsolved murders he was suspected of having committed. I met with them at the end of each day, and over pizza and wine we discussed what I would ask Kuklinski the next day. My challenge was to ask him questions that might provide factual information while making sure that his responses were visually compelling for the camera.

On camera, Kuklinski was sly but frank. He spoke of many murders, some at great length, but he was often stingy with the kind of specifics that might lead to new indictments. Perhaps he didnt want to go through another trial. I suspect he enjoyed the attention I gave him, and perhaps he feared that if he told me everything, I would lose interest in him. But his matter-of-fact retelling of his crimes was mesmerizing.

Several months later I went back into the prison with my film crew and a representative from HBO and conducted two more hours of interview, but something had changed. Unlike our previous experience, Kuklinski was uncooperative, and the effort was a waste of time.

I envisioned the Iceman project taking several formsfirst, as a documentary, then as a book, then as a feature filmand I proceeded with this in mind. As it turned out, the first two stages of my plan were accomplished in relatively quick succession. The Iceman Tapes: Conversations with a Killer was first broadcast in the spring of 1992. The book, The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer, written by crime writer Anthony Bruno, was published in hardcover in 1993. Both were very successful. The Iceman Tapes became one of HBOs highest-rated documentaries and was nominated for a Cable Ace Award. The book stayed in print for many years, and foreign editions were published in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. I felt confident that a movie deal would soon follow.

Unfortunately the toxic nature of the Kuklinski material seemed to infect the project itself. Success should have engendered further success, but instead it created greed, bruised egos, frustration, and enmity. The relationships I had worked so hard to build eroded around me. Suddenly I was seen as a Hollywood producer with all the negative attributes that phrase implies, and my motives became suspect. While my goal never changed and my intentions were exactly what they had been when I started, the tainted perceptions of others put obstacles in my path and kept me from making the film.