Table of Contents

BECAUSE EVERY BOOK IS A TEST OF NEW IDEAS

Praise from the UK for

How to Get Things Really Flat

You might not think that a book about cleaning could be

funny, but this made me laugh out loud. In the office. During

a quiet lunch hour.

Financial Times

Obviously my husband will be getting a pristine copy of How

to Get Things Really Flat. The author takes his task seriously, but

hes also a funny and fluent writer and this one just might

hang around to become an essential reference book as our two

young boys grow up.

Daily Telegraph

I was afraid that this was going to be another one of those tiresome blokes-are-crap-at-housework books, but its a strange delight, disarmingly written. Andrew Martin is lyrical about the vacuumingwith a special mention of his favourite attachment, the crevice nozzleand he gives the lowdown on feather dusters.

Sunday Telegraph

Andrew Martin has launched himself as an unlikely domestic

god. His hilarious book is a blokes guide to difficult stuff

like ironing, dusting, cleaning products and, yes, Christmas.

Daily Mail

Combining hilarious anecdotes with practical tips from

experts about housework for men, its debatable whether this is

really a gift for him, or you.

Woman & Home

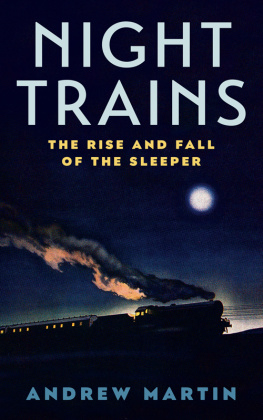

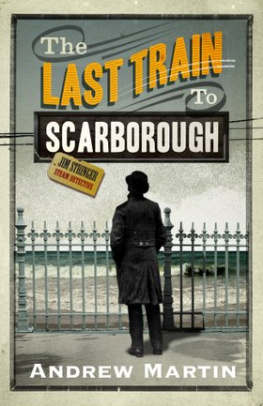

Also by Andrew Martin

THE JIM STRINGER NOVELS

The Necropolis Railway

The Blackpool Highflyer

The Lost Luggage Porter

Murder at Deviation Junction

Death on a Branch Line

OTHER NOVELS

Bilton

The Bobby Dazzlers

OTHER NONFICTION

Funny You Should Say That:

Amusing Remarks from Cicero to the Simpsons

This book is dedicated to, but not intended for, Lisa

PREFACE TO THE AMERICAN EDITION

Its very satisfying to write those words, but it seems strange to be doing so in connection with this subject. As I survey my notes for this book, scribblings such as Vacuumingbasic facts and Get more on dusting seem bizarre. That I should have accumulated a pile of paper about six inches thick on the various disciplines of housework seems odder still.

The belief that men are just not supposed to know about housework is particularly strong in the North of England, which is where I grew up. During my childhood, the region was still the industrial heart of Britain, as it had been since the early nineteenth century. A friend of mine recently said to me, Theres a great arrogance about northerners, isnt there? Thats because they come from the worlds first industrialized regionits there in their DNA. Personally, I think this empowering inner knowledge has been washed away on a tide of cappuccino, Frappuccino, drizzled pesto, and other manifestations of the service economy that have replaced industrial production. I grew up in York, a popular tourist destination for American visitors. The industry of York was rather reprehensibly pretty: railways and chocolate. But still, the medieval city walls, which today gleam white for the benefit of tourists, were once black from locomotive smoke, and I wasnt allowed to go near them if wearing a smart coat. At five oclock the men were released from the railway carriage worksthree thousand blokes riding wobbly bikes ten abreast down the road. At night I went asleep to sound of (or was kept awake by) the ghostly clanking of wagons being shunted. Most days, the air of the city was also permeated with the soft, deliquescing smell of roasted cacao beans from the two great chocolate factories. Today the carriage works is closed, and theres a huge, embarrassing empty space around the station where the freight-marshaling yards used to be. One chocolate factory is about to be turned into a hotel; the other survives, but in reduced circumstances, and you have to be standing in the right place at the right time to get the chocolate smell.

My grandfather was an engineer in one of the chocolate factories, and my father and mother both worked for British Rail. But then, when I was nine, my mother died, and my grief was compounded by social disorientation. Who would do the housework? The idea that my father might do it seemed a very radical piece of lateral thinking indeed. For one thing, this would require him to be at large in the kitchen and in the house generally, yet northern men at that time were hardly ever seen by my young eyes. They were remote, haggard figures. Youd see them going to work and coming back from work. Otherwise they were in bed or in the pub.

In Northern England, the deal was this: the man went to work in a factory or similar; the wife (and he often would employ the definite article when speaking of his spouse) got to stay at home, in return for which privilege she would do the houseworkand I do mean all of it. This division of labor was at its height in Edwardian times, when any working-class man who helped about the house would be an object of abuse: he was a dolly-mop or simply a nancy. The logic was that if this betrayer of the male sex was doing housework, then his wife must be destined for the factory. In my boyhood, the man who did housework was still a freak, even if he had no wife to send to the factory, and Ia self-conscious youthbecame particularly aware of my fathers anomalous position during Sunday lunchtimes when, just as the womens labors were at their most frenetic in the cooking of the big meal, the men strolled off to the pub. But my dad stayed at home, filling the kitchen with steam as he boiled the vegetables to death. Id watch the other fathers going past the kitchen window, passing out Hamlet cigars and laughing in anticipation of a couple of pints and a game of dominoes, and Id say, Dont you want to go to the pub, Dad?

No, I dont, now will you pass me the gravy mix?

Why didnt he want to go to the pub? It struck me that he was rather suspiciously keen on doing the housework. He was taking to it rather too well.

Then again, had he not also played professional football as a young man when hed turned out (admittedly only once) for York City, who were then not quite as negligible a footballing force as they subsequently became? Was he not a faster runner than me, as proved every year on Blackpool beach? Had he notduring a trip to Londonshoved a big man halfway down an escalator when hed ignored a polite Excuse me, repeated three times? Also, his housework specialty was ironing (he would carefully lay a thin piece of damp muslin over my school trousers and press down hard with the iron to give razor creases), and this skill, I knew, he had learned in the army.

I always had an iron under my control in the billet, my dad once told me, and I would do the ironing for the blokes who couldnt do it themselves. Id always iron the cooks uniform, and he paid me back with toast and tea.

My dad was no dolly-mop, and as I got older, I stopped worrying so much about it. Nevertheless, I felt it would be best for himsafer for his mental health, as it wereto minimize the amount of time he spent wearing an apron (because he would put one on for the heavier kitchen jobs). So I began to help him with the housework, in which activity lie the roots of this book.