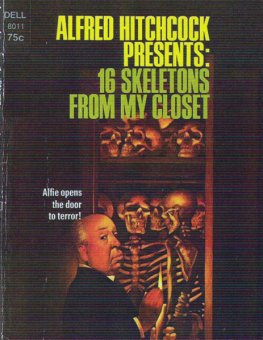

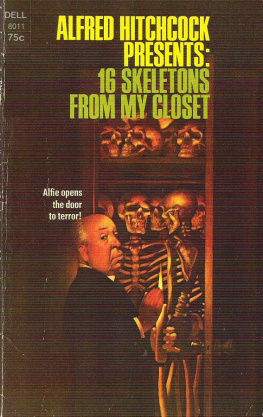

Alfred Hitchcock Presents:

16 Skeletons From My Closet

Shortly after the completion of shooting on my most recent motion picture, I remember reading about a murder which had occurred the day previous in the city of Chicago. Now, I can hardly think of a better place for the scene of a murder. Chicago has always seemed a perfect locale for such a crime: the cold wind coming in off Lake Michigan, long black cars speeding along major thoroughfares, the sudden, deadly sound of machine-gun fire. The perfect locale indeed.

However, the murder of which I speak was horribly disappointing. A matron of middle years, supposedly happily married for quite some time, went shopping in the afternoon and purchased a hat. The price for this headpiece was $39.98 "on sale." A fine buy, obviously. She brought it home proudly, and showed it to her spouse, just returned from a most difficult and trying day at the office. He, unfortunately, did not like the hat. Very calmly, then, the woman went to a desk drawer in the living-room, took from it a loaded thirty-eight caliber pistol, and shot her husband dead.

How dull. One shot and poof. How much better if she had emptied the pistol into the man in hysterical rage but no, a single shot.

* * *

It seems to me that when our century was newer the crime would not have happened in so pedestrian a manner. I very much doubt a pistol would have been used, since a pistol is decidedly not a woman's weapon, as so many mystery writers have been quick to point out for so many satisfying years. Perhaps a rolling-pin, a jungle knife brought back from the Amazon country years ago by the original owner who had traveled with Theodore Roosevelt, a dose of poison in the soup, a thin but strong cord across the top of the staircase

Such was the grandeur of yesteryear, when murder was done with flair and imagination.

Of course, we all recall the story of Miss Lizzie Borden, who took an ax and gave her parents forty whacks.

And then there was the gentleman on December 31, 1913, who stabbed his wife to death, dissected her body, and sent the pieces to friends and relatives with best wishes for a most enjoyable New Year.

The press would be much enlivened by a good garroting or a woman tied and left on a railroad track (of course, one would have to be sure the trains are still running).

I cannot promise such excitement in the future, but I can promise you a shudderingly good time in the pages to come.

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

Detectives should not be required to apprehend ghosts. It simply takes too much time. Moreover, though clothes may make the man, there's far more to a ghost than his bed sheet.

I do not believe in ghosts. Perhaps I do not believe in ghosts because I refuse to believe in ghosts and my mind rejects the possibility and seeks other explanation. In the Troy affair such explanation, for me, involved death-wish, hallucination, guilt complex, retribution, self-punishment and dual personality, but there again I am out of my ken: I am not a psychiatrist, I am a private detective. There are those who disagree with my conclusions, and you may be one of those. So be it, then. All I can do is render the events just as they occurred, beginning with that bright-white afternoon in January when my secretary ushered Miss Sylvia Troy into my office.

"Miss Sylvia Troy," said my secretary and departed.

"I'm Peter Chambers," I said. "Won't you sit down?"

She was small, quite good-looking, very feminine, about thirty. Close-cut wavy russet-red hair was capped about a smooth round face in which enormous dark-brown eyes would have been beautiful except for a flaw in expression almost impossible to put into words. There is only one word haunted! and that word, of course, is susceptible to so many different interpretations. Her eyes were far away, gone, out of her, not part of her, remote and lost. She remained standing while I, still seated behind my desk, squirmed uneasily.

"Please sit down," I said in as cordial a tone as I could muster within the embarrassment of trying to avoid those peculiarly-luminous, strangely-isolated, frightened eyes.

"Thank you very much," she said and sat in the chair at the side of my desk. She had a soft lovely voice, almost a trained voice as a professional singer's voice may be termed trained: it was round-voweled, resonant, beautifully-pitched, very feminine, melodious. She was wearing a red wool coat with a little black fur collar and she was carrying a black patent-leather handbag. She opened the handbag, extracted three hundred dollars, snapped shut the bag, and placed the money on my desk. I looked at it, but did not touch it.

"Not enough?" she said.

"I beg your pardon?" I said.

"The way you're looking at it."

"Looking at what?" I said.

"The money. Your fee. I'm sorry, but I can't afford any more."

"I'm not looking at it in any special way, Miss Troy. I'm just looking at it. Three hundred dollars may be enough or not enough depending upon what you want of me."

"I want you to lay a ghost."

"What?"

"Please, sir, Mr. Chambers," she said, "I'm deadly serious."

"A ghost "

"A ghost who has already killed one person and threatens to kill two others."

I directed my squirming to seeking in my pockets and finding a cigarette. I lit it and I said, "Miss Troy, the laying of ghosts is not quite my department. If this so-called ghost of yours has killed anyone, then you've come to the wrong place. There are constituted authorities, the police "

"I cannot go to the police."

"Why not?"

"Because if I tell my story to the police I would be incriminating myself and my two brothers in" She stopped.

"In what?"

"Murder."

There was a pause. She sat, limply; and I smoked, nervously.

Then I said, "Do you intend to tell me this story?"

"I do."

"Won't that be just as incriminating "

"No, no, not at all," she said. "I must tell you because something must be done, because somebody you, I hope must help. But if you repeat what I tell you to the police, I will simply deny it. Since there is no proof, and since I would deny what you might repeat, nobody would be incriminated."

It was coming around to my department. People in trouble are my department. Had there been no mention of a ghost, it would have been completely and familiarly in my department. But it was sufficiently in my department for me to tap out my cigarette in an ashtray, pull the money over to my side of the desk, and say, "All right, Miss Troy, let's have it."

"It begins about a year ago. November, a year ago."

"Yes," I said.

"There are or were four of us in the family."

"Four in the family," I said.

"Three brothers and myself. Adam was the oldest. Adam Troy was fifty when he died."

"And the others?"

"Joseph was thirty-six. Simon is thirty-two. I am twenty-nine."

"You say Joseph was thirty-six?"

"My brother Joseph killed, himself supposedly killed himself three weeks ago."

"Sorry," I said.

"And now if I may just a little background."

"Please," I said.

"Adam, so much older than any of us, was sort of father to all of us. Adam was a bachelor, rich and successful he always had a knack for making money while the rest of us" she shrugged "when it came to earning money, we were no shining lights. Joseph was a shoe-salesman, Simon is a drug clerk, and I'm a nightclub performer and, I must confess, a pretty bad one at that."

"Nightclub performer. Interesting."

"I do voices, you know? I used to be a ventriloquist. Now I'm a mimic; imitations, that sort of thing. Nothing great. I get by."

Next page