Table of Contents

Praise forWhen That Rough God Goes Riding

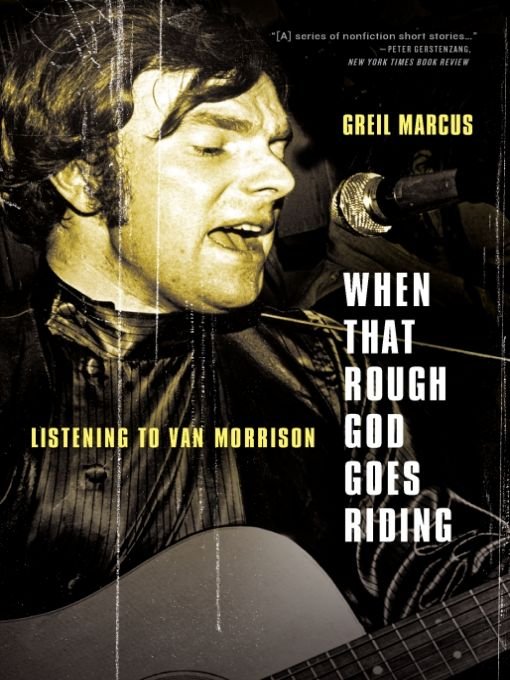

Writing about the songs of Van Morrison is rightly seen as something of a paradox. Perhaps thats because, for all his scholarly use of multiple musical styles and his reference to Yeats and Joyce, the Belfast Cowboys work is more sensual than it is intellectual. Which makes the renowned rock critic Greil Marcus, whos written definitively on Elvis and Bob Dylan, the right man to plumb that work. Combining an incantatory prose style with careful reporting and inventive, sometimes infuriating judgments, Marcus manages to illuminate Morrisons cerebral soul musiceven if, as the singer once claimed, the process is beyond words.

PETER GERSTENZANG, New York Times Book Review

No critical testimonial is more welcome than this assessment of Morrisons work by one of Americas most astute cultural critics.... Marcus is informed and insightful. Particularly illuminating are his observations on the tensions between Morrisons roles as singer and songwriter, and on Morrisons ongoing quest for the yarraghfleeting, elusive moments of transcendence. Morrisons volatile idiosyncrasy and diverse oeuvre make his career difficult to appraise, but Marcus convinces us of its singular importance.

GORDON FLAGG, Booklist

[Marcus is] literate, brainy, and fearless in making cross-genre comparisons.

JEFF BAKER, Portland Oregonian

Written in prose as free-associative as the music it concerns, When That Rough God Goes Riding derives energy from the fact that Marcus was present at many of the landmark moments hes exegizing.

TED SCHEINMAN, Washington City Paper

When That Rough God Goes Riding explores moments of contradiction, sublime beauty, audacity, failure, and grace in the singer-songwriters career with a keen ear, weaving the rich thoughtfulness weve come to expect from one of Americas best cultural critics and historians into an elegantly structured series of staccato essays which reveal Marcus fascination with Van Morrisons music.

ROBERT LOSS, Popmatters.com

This is the book that Van Morrisons artistry has long deserved, and The Mans devotees will celebrate its blend of eloquence, passionate scholarship and soulfulness. [When That Rough God Goes Riding] superbly fulfills criticisms primary function: It sends you for the first or 100th time to the works of art on which it muses, better equipped to experience whats always been there.

JON REPP, Cleveland Plain-Dealer

[Marcus] ability to couple shrewd music criticism, historical perspective, and broader genre analysis makes his work an adventurous read.... Marcus doesnt attempt to tidily summarize Morrisons life and career, but he does provide plenty of thought-provoking insights into this enigmatic performer, and his slipstream of references results in a fascinating meditation on Morrisons oeuvre. You wind up wanting to pull out and listen to your Morrison albums and hunt down the many bootleg recordings that Marcus references here, searching for that elusive yarragh.

MICHAEL BERICK, San Francisco Chronicle

Marcus is a smart respite from the raging stupidity and antiintellectualism on every front, and yet knows how to have rock n roll fun at the same time.

MICHAEL SIMMONS, LA Weekly

For Dave Marsh

NORTHERN MUSE. GREEK THEATRE, BERKELEY. 3 MAY 2009

The fourteen-piece band assembled for a concert in which Van Morrison was to perform the whole of his forty-oneyear-old album Astral Weeks so dominated the stage you might not have even noticed the figure seated at the piano; the sound Morrison made when he opened his mouth seemed to come out of nowhere. It was huge; it silenced everything around it, pulled every other sound around it into itselfMorrisons own fingers on the keys, the chatter in the crowd that was still going on because there was no announcement that anything was about to start, cars on the street, the ambient noise of the century-old open-air stone amphitheatre, where in 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt spoke, where in 1906 Sarah Bernhardt appeared to cheer on San Francisco as it dug out of its ruins, where in 1964 the student leader Mario Savio rose to speak to the whole of the university gathered in one place and was seized by police the instant he stood behind the podium as the crowd before him erupted in screams, where Senator Robert F. Kennedy spoke in 1968, days before he was shot. The first word out of Morrisons mouth that night, if it was a word, not just a sound, something between a shout and a moan, was, you could believe, as big as anything that ever happened on that stage.

INTRODUCTION

In 1956, the stiff and tired world of British pop music was turned upside down by Lonnie Donegans Rock Island Line, a skiffle version of a Lead Belly song, played on guitar, banjo, washboard, and homemade bass. Like thousands of other teenagers, John Lennon put together his own skiffle band in Liverpool that same year; Van Morrison, born George Ivan Morrison in 1945 in East Belfast, in Northern Ireland, formed the Sputniks in 1957, the year the Soviet Union put the first satellite into orbit and John Lennon met Paul McCartney. Morrison would never find such a comrade, and, unlike the Beatles, he would never find his identity in a group. Whether in Ireland, England, or the United States, he would always see himself as a castaway.

East Belfast was militantly Protestant, but Morrisons parents were freethinkers; even after his mother became a Jehovahs Witness for a time in the 1950s, his father remained a committed atheist. The real church in the Morrison household was musical. There was always the radio (My father was listening to John McCormack); more obsessively, there was my fathers vast record collection, 78s and LPs by the all-American Lead Belly, and within the kingdom of his vast repertoire of blues, ballads, folk songs, protest songs, work songs, and party tunes that dissolved all traditions of race or place, the minstrel and bluesman Jimmie Rodgers, cowboy singers of the likes of Eddy Arnold and Gene Autry, the balladeer Woody Guthrie, the hillbilly poet Hank Williams, the songsters Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, the gospel blues guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpeand later Muddy Waters, Howlin Wolf, Little Walter, John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Williams, all of them magical names. Thus when the thirteenyear-old singer, guitar banger, and harmonica player Van Morrison went from the Sputniks to Midnight Special, named for one of Lead Bellys signature numbersand after that from Midnight Special to the Thunderbolts, a would-be rockn roll outfit that tried to catch the thrills of Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, and from the Thunderbolts to the Monarchs Showband, a nine-man outfit with a horn section, choreographed shuffles, and stage suits that would play your company dinner, your Christmas party, your wedding, and which in the early 60s toured Germany offering Ray Charles imitations to homesick GIs, only a patch of the map Morrison carried inside himself had been scratched.

In 1964, in Belfast, with the band Them, Morrison began to find his style: the blues singers marriage of emotional extremism and nihilistic reserve, the delicacy of a soul singers presentation of a bleeding heart, a folk singers sense of the uncanny in the commonplace, the rhythm and blues bandleaders commitment to drive, force, speed, and excitement above all. The groups name, calling up the 1954 horror movie about giant radioactive ants loose in the sewers of Los Angeles, was full of teenage menace: