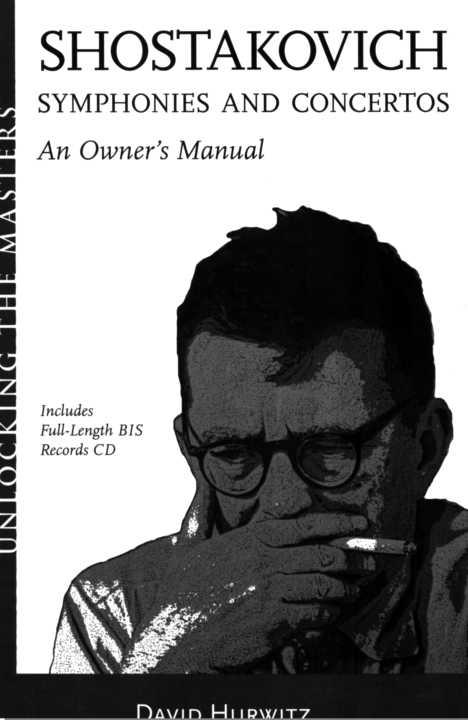

Unlocking the Masters Series, No. 9

To my dear friends, Claire and Christophe, with fondest hopes that their life together utterly lacks the drama of a Shostakovich symphony!

Contents

Part I: Shostakovich's Musical Language

Part 2: Early-Period Works

Part 3: Middle-Period Works

Part 4: Late-Period Works

Part 1

Shostakovich's Musical

Language

The Shostakovich Question

11 intensely expressive music that does not purport to tell a story or make obvious reference to anything beyond basic human emotions including most of the symphonies and concertos of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75)-naturally begs the question of what it is that the composer is trying to say. The case of Shostakovich presents this problem in a particularly acute form. So much so, in fact, that an entire field of academia has been created in order to attempt to ferret out any biographical or programmatic subtexts concealed in his major works. That such hidden meanings exist is beyond question. The composer himself suggested as much. However, the degree to which his verbal statements can be believed and the accuracy, with which they have been transmitted remains an object of great controversy embodied in numerous books and articles, and much very real (if often entertaining) hostility among scholars and researchers.

11 intensely expressive music that does not purport to tell a story or make obvious reference to anything beyond basic human emotions including most of the symphonies and concertos of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75)-naturally begs the question of what it is that the composer is trying to say. The case of Shostakovich presents this problem in a particularly acute form. So much so, in fact, that an entire field of academia has been created in order to attempt to ferret out any biographical or programmatic subtexts concealed in his major works. That such hidden meanings exist is beyond question. The composer himself suggested as much. However, the degree to which his verbal statements can be believed and the accuracy, with which they have been transmitted remains an object of great controversy embodied in numerous books and articles, and much very real (if often entertaining) hostility among scholars and researchers.

The study of Shostakovich's life is indeed a fascinating subject, perhaps the seminal opportunity to examine the complex relationship between artistic genius and the cultural policies of an evil, totalitarian regime. Exactly how the music fits into this equation is a puzzle that resists easy solution. After all, the entire point of hidden meanings is that they remain hidden. Shostakovich is gone, taking his secrets with him to the grave.

Those of his friends who were privy to his private thoughts (or who claim that they were) have spoken. The sum total of what they have to say, however interesting or moving biographically, not only has turned out to be largely unenlightening as an aid to understanding his music as such, but it pales beside the elemental power and eloquence of the various works themselves.

I can think of only one major exception to the above generalization among accounts of the composer available in English, written by those who actually knew him well, and this is the portrait of Shostakovich offered by Galina Vishnevskaya, the greatest Russian soprano of the twentieth century and wife of' the world-famous cellist /conductor Mstislav Rostropovich. Her autobiography, Galina: A Russian Story remains arguably the finest personal memoir of artistic life under the Soviet regime, and her summary and description of the "Shostakovich question" is so succinctly compelling and complete, so useful in establishing the context for the following discussion of the music itself, that it deserves to be quoted at length.

Vishnevskava picks up the story in 1935, when the composer was twenty-nine and basking in the success of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk:

Dmitri Shostakovich was ascending the very heights of fame young, brilliant, and recognized not only in Russia but throughout the world. His First Symphony, written when he was only nineteen, had, by the time he was twenty, crossed the Soviet borders to be performed by the best orchestras under the greatest conductors: Arturo Toscanini, Bruno Walter, Leopold Stokowski, Serge Koussevitsky. And (luring those fateful years especially, his music was performed often in America. In addition to his symphonies, Lady Macbeth premiered in New York at the Metropolitan Opera, in Cleveland, and in Philadelphia. It was also heard from one end of Europe to another from the London radio with Albert Coates conducting, to Bratislava, Czecholovakia. Lady Macbeth was conquering the world.

But how could such fame be tolerated in the land of "equality and brotherhood"? Why is Shostakovich being performed everywhere? What's so special about him? The international recognition of that Soviet composer was bound to cost him something in his own country. He had dared to outgrow the scale the Party had been measuring him by. He had to be whittled down to size reduced to the general level of Soviet culture, to so-called Socialist Realism. The Composer's Union- --save for a few outstanding composers like Sergei Prokofiev, Aram Khachaturian, Reinhold Gliere, and Nikolai Myaskovsky-- was made up of nonentities who packed Party cards and sucked up to the great Stalin and the Party with their worthless odes and marches. Shostakovich's genius and personality were more than out of place in that milieu. Amid that stifling mediocrity and pretense, his brilliance and honesty looked positively indecent.

On January 28, 1936, a month after the premiere of Lady Macbeth at the Bolshoi, the composer read about his opera in a crushing, crudely vicious Pravda article entitled "A Muddle Instead of Music." (And a few days later, on February 5, it was followed by another acerbic article, "Ballet Fakery," written about The Sparkling Steam.)

From the very first minute of the opera, the listener is dumbfounded by a deliberately dissonant, confused flow of sounds. Fragments of melody, the beginnings of a musical phrase, sink down, break loose, and again vanish in the din, grinding and screeching. To follow this "music" is hard, and to remember it is impossible.

... The composer of Lady Macbeth of f Mtsensk had to borrow his nervous, convulsive, epileptic music from jazz in order to endow his characters with "pas sion"... At a time when our criticism including music criticism is pledged to Socialist Realism, the stage serves up to us, in the work of Shostakovich, the crudest kind of naturalism.

And all of it is crude, primitive, vulgar ... The music quacks, moans, pants, and chokes in order to render the love scenes as naturally, as possible. And "love" is smeared all over the opera in the most vulgar form.

In the Party's ideological war, Shostakovich was the first musician to take a blow, and he realized it was a fight to the death for his conscience as an artist and creator. In the Soviet Union, the appearance in Pravda of' an article like that is tantamount to a command: beat him, cut him down, tear him to pieces. The victim is tagged an enemy, of the people, and a gang of worthless characters, openly supported by the top Party echelon, rushes forward to curry favor and make their careers. A fall from a big horse is bound to be painful: Shostakovich was badly wounded by, that blow from the government, with which he had never had a confrontation before. But he did not accept their "criticism"; he did not repent. For two years he wrote no response, although they fully expected him to. And however Soviet musicologists may try today, as they collect his public statements crumb by crumb, they can't find anything from those years. It was a heroic silence, a symbol of disloyalty and resistance to the regime. And very few would have been able to do as he did. Shostakovich kept quiet and to himself, not speaking his mind until two years later. He finally made his statement on November 21, 1937, in Philharmonic Hall in Leningrad with his Fifth Symphony, that extraordinary masterpiece, which, as our Dmitri Dmitriyevich told us, was autobiographical.

11 intensely expressive music that does not purport to tell a story or make obvious reference to anything beyond basic human emotions including most of the symphonies and concertos of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75)-naturally begs the question of what it is that the composer is trying to say. The case of Shostakovich presents this problem in a particularly acute form. So much so, in fact, that an entire field of academia has been created in order to attempt to ferret out any biographical or programmatic subtexts concealed in his major works. That such hidden meanings exist is beyond question. The composer himself suggested as much. However, the degree to which his verbal statements can be believed and the accuracy, with which they have been transmitted remains an object of great controversy embodied in numerous books and articles, and much very real (if often entertaining) hostility among scholars and researchers.

11 intensely expressive music that does not purport to tell a story or make obvious reference to anything beyond basic human emotions including most of the symphonies and concertos of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75)-naturally begs the question of what it is that the composer is trying to say. The case of Shostakovich presents this problem in a particularly acute form. So much so, in fact, that an entire field of academia has been created in order to attempt to ferret out any biographical or programmatic subtexts concealed in his major works. That such hidden meanings exist is beyond question. The composer himself suggested as much. However, the degree to which his verbal statements can be believed and the accuracy, with which they have been transmitted remains an object of great controversy embodied in numerous books and articles, and much very real (if often entertaining) hostility among scholars and researchers.