PORTFOLIO / PENGUIN

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Portfolio / Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2015

Copyright 2015 by Zac Bissonnette

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

This book was not authorized, prepared, approved, licensed or endorsed by Ty, Inc.

Courtesy Joy Warner: Insert

Courtesy Harold Nizamian:

Courtesy of the author:

Courtesy Sondra Schlossberg:

Courtesy Patricia Smith-Roche:

Courtesy Lina Trivedi:

Courtesy Peggy Gallagher:

Courtesy Lauren Boldebuck:

Kevin R. Johnson/Press Line Photos/Corbis:

Andrew Nelles/AP/Corbis:

Nick Presniakov:

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bissonnette, Zac.

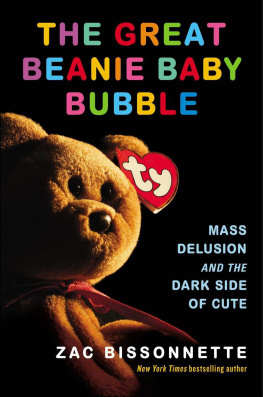

The great Beanie Baby bubble : mass delusion and the dark side of cute / Zac Bissonnette.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-60698-8

1. Warner, Ty, 1944 2. Ty, Inc.History. 3. Beanie Babies (Trademark)Collectors and collectingHistory. 4. Toy industryUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

HD9993.T694T923 2015

338.7'688724dc23

2014038639

Version_1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The greatest toy salesman in the world looked out at his 250 employees gathered for the Ty Inc. holiday party.

Wow! fifty-four-year-old Ty Warner said. Ive never been in a room with so many millionaires!

The salespeople cheered because it wasnt an exaggeration. It was December 12, 1998, and Ty Inc. was three weeks away from closing out a year of sales that would break nearly every record in the annals of the toy industry. Andi Van Guilder was seated in the back with the relatives shed hired to answer the phones that hadnt stopped ringing with orders for Beanie Babies in close to three years. She thought about it. In 1993, shed made less than $30,000 lugging trunks of porcelain figurines and collector plates to stores in two states. In 1998, selling Beanie Babies to independently owned toy and gift shops in Chicagos northern suburbs had paid her more than $800,000 in commissions. She was thirty years old. Life was perfect.

The applause died down. Ty made the announcement hed been planning for weeks: he would be giving all his employees Christmas bonuses equal to their annual salaries.

Pandemonium ensued. Ty was their God, Faith McGowan, Tys then girlfriend, remembers. He basked in the adulation of the workers who, in the span of three years, had helped make him the richest man in the American toy industry. His annual sales for 1998 had surpassed $1.4 billionvirtually all of it coming from the $2.50 wholesale price on beanbag animals that frenzied speculators had turned into a craze that was the twentieth-century American version of the tulip bubble in 1630s Holland.

Ty had created the toys in 1993 in the hope that they would be popular among children, but they had become so much more than that; and they had also become so much less than that because most collectors, aware of the soaring values for the rarest styles, wouldnt let their children anywhere near them. Humorist Dave Barry explained the mania in a 1998 column: Beanie Babies were originally intended as fun playthings for children, but as the old saying goes, Whenever you have something intended as innocent fun for children, you can count on adults to turn it into an obsessive, grotesquely over-commercialized hobby with the same whimsy content as the Bataan Death March.

The first buyers had been children with allowances. Then their moms had started collecting. By the time of the 1998 Ty Christmas party, Van Guilder remembers, it was mostly creepy, belligerent men she saw lined up when she dropped in to check on retailers. The little animals with names like Seaweed the Otter and Gigi the Poodle had become, as Van Guilder puts it, something really cute that just brought out the worst in people.

The worst in people was inspired by a popular belief that Beanie Babies were a long-term investment. A self-published author sold more than three million copies of a book that touted ten-year predictions for their values. The magazine Mary Beths Beanie World, started by a self-described soccer mom, reached one million copies in paid monthly circulation. In it, a full-page, full-color ad for Smart Heart tag protectors led with this headline: How Do You Protect an Investment That Increases by 8,400%? The answer was to buy hard-shell lockets in which to encase the animals heart-shaped paper tags that read Safety Precaution: Please remove all swing tags before giving this item to a child. More than any other consumer good in history, Beanie Babies were carried to the height of success by a collective dream that their values would always rise.

Warners announcement of bonuses wasnt his only gift to his employees at the Christmas party. He also presented them with #1 Bear, a signed and numbered red Beanie Baby with the number 1 stitched onto the chest. The inside of the hangtag explained that only 253 of the bears had been produced. It also listed the companys achievements for the year: more than $3 billion in retail sales, number one in the gift category, number one in collectibles, and number one in cash register area sales.

The workers inspected the bears and cheered some more. No doubt some were moved by sentiment, but they also knew that the bear could be listed on eBay, where Beanie Babies comprised 10 percent of all sales. On eBay, Beanie Babies sold for an average of $30six times the price they had originally retailed for. Within a few weeks, #1 Bears would be selling for $5,000 or more apiece.

Not everyone at the luncheon was so thrilled. Faith McGowan sat quietly. In late 1993, Warner had shown her and her two daughters from her previous marriage who lived with them the first prototype for Legs the Frog. Since then, the animals had been the sole focus of their time together. Even as sales exploded, Ty personally designed every piece the company put out, and that meant spending several months each year at the factories in Asia. The frantic pace of their life together was exhausting, and Ty, a throwback to an entrepreneurial archetype that no longer exists, wasnt slowing down. Today, most rags-to-megariches stories involve hot technology, venture capital, and high-profile initial public offerings. Ty skipped all of that, marketing his own products based on his own ideas and the feedback of everyone around him without ever hiring a marketing consultant or assembling a focus group. Hed been the businesss only shareholder since hed started it in his condo in 1983, and when the investment bankers came peddling nine- and then ten-figure deals, Warner declined the dinner invitations. Most guys would at least have the decency to jerk you around, remembers one banker. He wouldnt even talk to you.