I pant, I sink, I tremble, I expire.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Contents

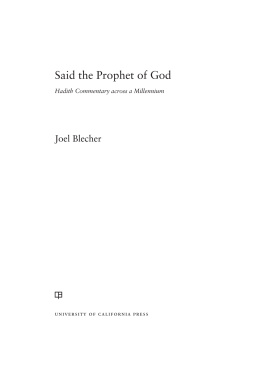

Max Blechers Adventures

This is a book that soothes without sentimentality. Blecherchronicled his dying from both the interior of his body and the outside ofnonexistence. He made that veil permeable: his words are vehicles traveling throughthe opaque membrane that surrounds the seemingly solid world. These are theadventures of the inside and the outside exchanging places, while being somehowexactly the same in the light of Blechers extraordinary sensibility. Nobody knowshow to die. Max Blecher, because he was young and a genius, suggests a way thatinvestigates, rediscovers life, and radiates beauty from suffering.

Ordinary words lose their validity at certain depths of the soul.

Max Blechers soul was a fearless journalist who reported what his hypersensitivesenses and immense intelligence uncovered about the world we think we know. Theworld as definitively constituted had lain waiting inside me forever and all I didfrom day to day was to verify its obsolete contents. After the discovery that thisis not the real world, he finds it to be the projection of a text that tells a storywhich erases the world as it appears to be: All at once the surfaces of thingssurrounding me took to shimmering strangely or turning vaguely opaque like curtains,which when lit from behind go from opaque to transparent and give a room a suddendepth. But there was nothing to light these objects from behind, and they remainedsealed by their density, which only rarely dissipated enough to let their truemeaning shine through.

This is not Surrealism, as critics sometime saw it, but hyper-realism. Blechercorresponded with Andr Breton, and was chronologically situated in a string ofJewish-Romanian geniuses: Tristan Tzara (b. 1886), Benjamin Fondane (b. 1898),Victor Brauner (b. 1903), and Gherasim Luca (b. 1913). Each of those writerslaunched a precocious revolution related to Surrealism, with an urgency prompted byan imminent and cataclysmic future. Yet, unlike his peers, for Blecher the urgencyof Time unfolds with a rigorous diagnostic probity that will not yield to anyunreflecting words. The games of language so beloved by Surrealists are there onlyto be disposed of.

Glossing the nonsense conversation he enjoys with a friend:

What I found in that banter was more than the slightly cloying pleasure of plunginginto mediocrity; it was a vague sense of freedom: I could, for instance, vilify thedoctor to my hearts content even though I knewhe lived in theneighborhoodthat he went to bed every night at nine... We would go on andon about anything and everything, mixing truth and fancy, until the conversationtook on a kind of airborne independence, fluttering about the room like a curiousbird, and had the bird actually put in an appearance wed have accepted it as easilyas we accepted the fact that our words had nothing to do with ourselves... Backin the street, I would feel I had emerged from a deep sleep, yet I still seemed tobe dreaming. I was amazed to find people talking seriously to one another. Didntthey realize one could talk seriously about anything? Anything and everything?

This is the nothing that is acquiring mass and is already heading for the worldthat Blecher feels becoming nothing but the mere traces of a once serious life. Inthe unfolding researches of his childhood, he has time to uncover in dusty atticsthe faded remains of gone worlds: letters, photographs, and paintings moresubstantial than the present, which evanesces as he writes, like a scene viewedthrough the wrong side of a binocular, perfect in every detail but tiny and faroff.

There is an inverted nostalgia here, a nostalgia for the present that has alreadytaken hold of the writer who is composing both his own and his decades epitaph.Blecher, like Proust, endows places and objects from the past with the ability toproject an independent existence more real than the present. This world hidesanother, open only to the genius of child-wonder and adolescent desire.Adventures in Immediate Irreality is not a memoir, a novel, or a poem,though it has been called all those names, and compared rightly with the works ofProust and Kafka. Blecher belongs in that company for the density and lyrical forceof his writing, but he is also a recording diagnostician of a type the twentiethcentury had not yet fully birthed, but the twenty-first is honoring in the highestdegree.

The place of these adventures is probably Roman, the provincial Romanian city wherehe was born in 1909, a place small enough to explore, and conventional enough tograsp. The time is childhood and adolescence in the still new twentieth century. Theprobing instrument is his body rushing to work for as long as the liberty of his ageand his vitality allow. Blecher didnt outlive his unfettered genius. In 1928, whilestill in medical school in Paris, he was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis. He wastreated at sanatoriums in Berck-sur-Mer in France, Leysin in Switzerland, andTechirghiol in Romania. For the last ten years of his life, he was confined to bed,immobilized by the disease. Despite his condition, he wrote and published his firstpiece in 1930, a short story called Herrant in Tudor Arghezis literary magazineBilete de papagal, contributed to Andr Bretons literary review LeSurralisme au service de la rvolution and corresponded with Breton, AndrGide, Martin Heidegger, Ilarie Voronca, Geo Bogza, and Mihail Sebastian. In 1934, hepublished Corp transparent, a volume of poetry. In 1935, he was moved to ahouse on the outskirts of Roman where he wrote and published his major works,ntmplri n irealitate imediat (Adventures in Immediate Irreality)and Inimi cicatrizate (Scarred Hearts), as well as short prose pieces,articles, and translations. In 1938 he died, at the age of twenty-eight.

Blechers genius is also the genius of his disease, and the timing of his death: Ienvied the people around me who are hermetically sealed inside their secrets andisolated from the tyranny of objects. They may live out their lives as prisoners oftheir overcoats, but nothing external can terrorize or overcome them, nothing canpenetrate their marvelous prisons. I had nothing to separate me from the world:everything around me invaded from head to toe; my skin might as well have been asieve. The attention I paid to my surroundings, nebulous though it was, was notsimply an act of will: the world, as is its nature, sank its tentacles into me; Iwas penetrated by the hydras myriad arms. Exasperating as it was, I was forced toadmit that I lived in the world I saw around me; there was nothing for it. Thosehermetically sealed people, in their healthy bodies and apparently fortunatelongevity, were going to go on living in the coming decade. Max Blecher, whomnothing separated from the world, had the good luck to die in 1938, freed into theoutside before the 1940s.

Vizuina luminat: Jurnal de sanatoriu (TheLit-Up Burrow: Sanatorium Journal) was published posthumously in part in 1947 and infull in 1971. Beginning in the mid-1970s his books were translated into French,German, Spanish, Czech, Hungarian, Dutch, Swedish, Italian, Polish, and English. Thetwenty-first century is even more wildly receptive to Max Blecher.

For a moment I had the feeling of existing only in the photograph. Max Blecherwrote this sentence while Roman Vishniac was capturing a multitude whose membersceased to exist soon after he photographed them. Those images of people, whoseprovincialism was nearly absolute, later toured the world. This sentence by Blecherresonated for Walter Benjamin, himself in the grip of reproductiveextinctionwhat the twentieth century already had inscribed in its DNA. It isa fountain-sentence, a