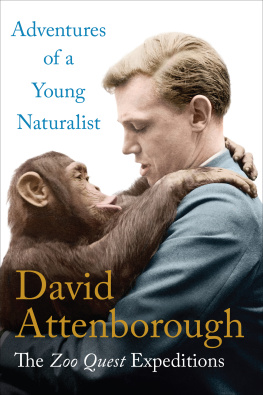

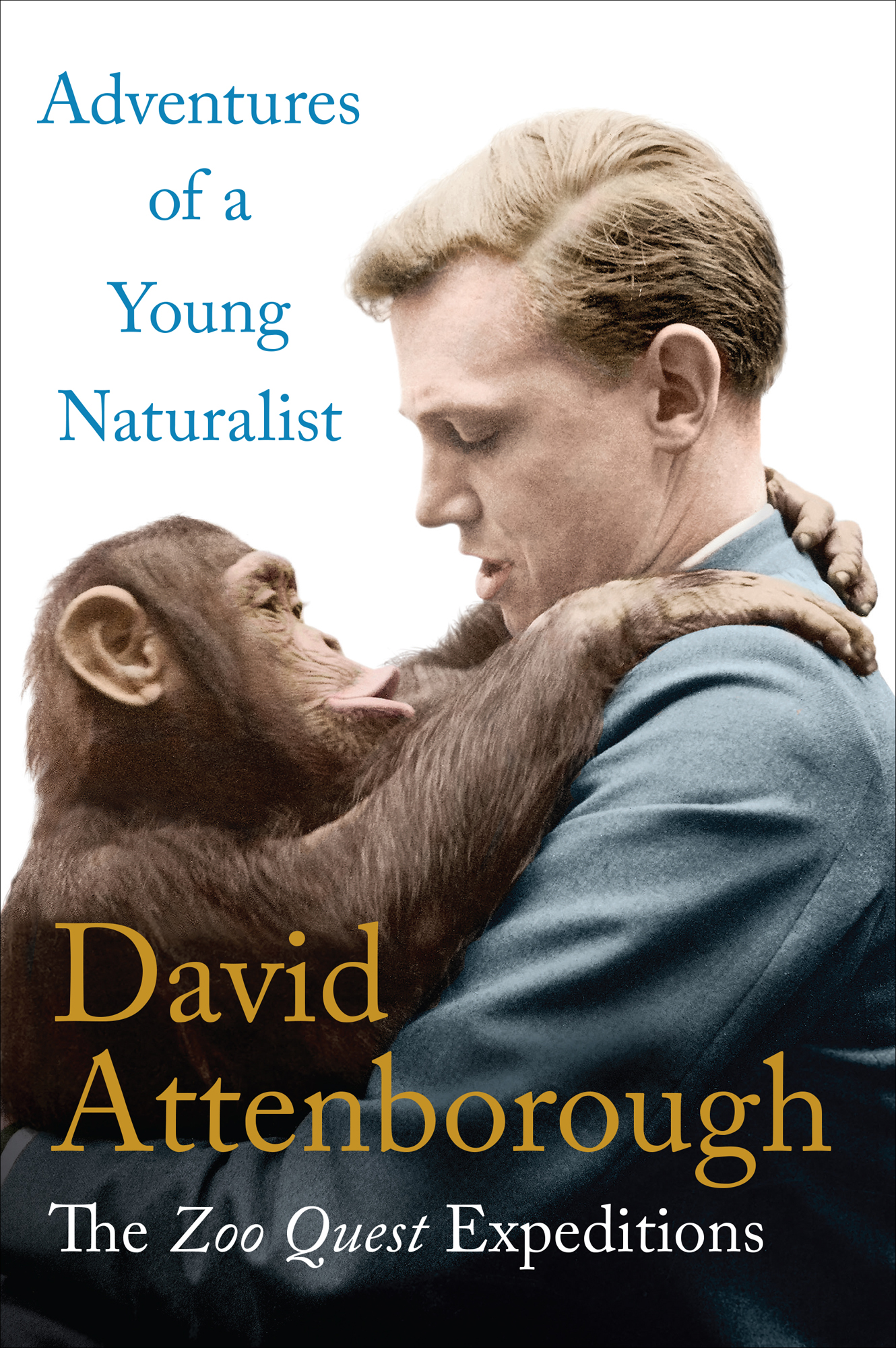

A DVENTURES OF A Y OUNG N ATURALIST

Also by David Attenborough

Zoo Quest to Guiana (1956)

Zoo Quest for a Dragon (1957)

Zoo Quest to Paraguay (1959)

Quest in Paradise (1960)

Zoo Quest to Madagascar (1961)

Quest Under Capricorn (1963)

Life Stories (2009)

New Life Stories (2011)

Life on Air (2014)

The Tribal Eye (1976)

The First Eden (1987)

Life on Earth (1979)

The Living Planet (1984)

The Trials of Life (1990)

The Private Life of Plants (1995)

The Life of Birds (1998)

The Life of Mammals (2002)

Life in the Undergrowth (2005)

Life in Cold Blood (2008)

New York London

1956, 1957, 1959 by David Attenborough

Introduction 2017 by David Attenborough

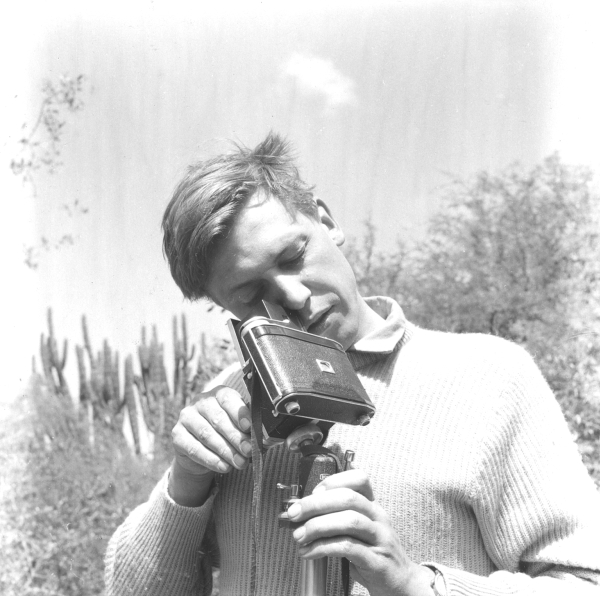

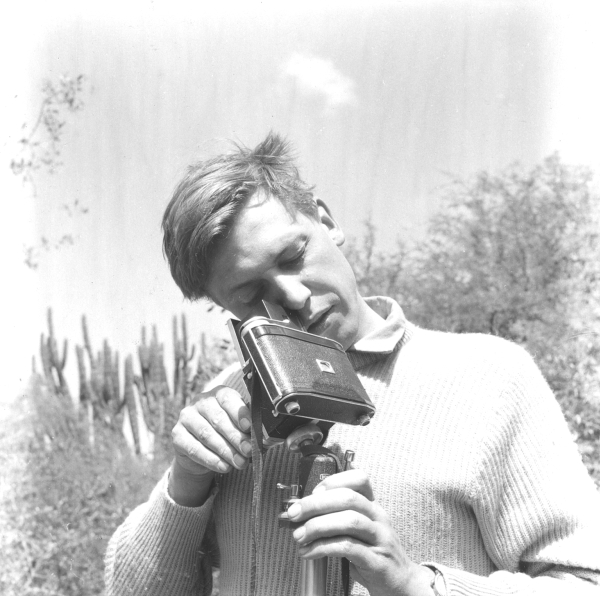

Photographs David Attenborough

Jacket photograph David Attenborough

First published in the United States by Quercus in 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

eISBN 978-1-63506-071-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Attenborough, David, 1926- author.

Title: Adventures of a young naturalist : the zoo quest expeditions / David Attenborough.

Description: New York, NY : Quercus, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017048329 (print) | LCCN 2017053767 (ebook) | ISBN 9781635060713 (ebook) | ISBN 9781635060720 (library ebook edition) | ISBN 9781635060690 (hardback) | ISBN 9781635060706 (paperback) | ISBN 9781635060713 (eISBN)

Subjects: LCSH: Attenborough, David, 1926- | Attenborough, David, 1926Travel. | Wild animal collecting. | Zoology. | Zoological specimensCollection and preservation. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Adventurers & Explorers. | SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Zoology / General.

Classification: LCC QL61 (ebook) | LCC QL61 .A86 2018 (print) | DDC 590dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017048329

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.quercus.com

C ONTENTS

T hese days zoos dont send out animal collectors on quests to bring em back alive. And quite right too. The natural world is under more than enough pressure as it is, without being robbed of its most beautiful, charismatic and rarest inhabitants. Now most of a zoos crowd-attracting specieslions, tigers, giraffes and rhinoceros, even lemurs and gorillashave been born in zoos and kept track of in stud books, so that individuals can be exchanged internationally without incurring problems of in-breeding. They can then play a valuable part in familiarizing visitors with the splendors of the natural world and in explaining the importance and complexities of conservation.

But it was not always so. London Zoo was founded in 1828 by men of science who were, at that time, still concerned with the important but almost impossible task of compiling a catalog of all the species of animals alive today. Some were sent to it from distant parts of the world as dead specimens. Others arrived alive and were put on display in the Societys gardens in Regents Park. But both kinds ended up as well-studied anatomical specimens and carefully preserved. Needless to say, special attention was paid to finding species that no other zoo had ever possessed, and that ambition, to some extent, still lingered on even in the 1950s when I visited one of the Zoos curators with an idea for a new kind of television program.

Television then was also very different from what it is today. There was only one network, produced by the BBC, which could only be seen in London and Birmingham. All its programs came from two small studios in Alexandra Palace, in north London. They were the same studios and indeed the same cameras that in 1936 had provided the first regular television service in the world. Transmissions were suspended in 1939 on the outbreak of the Second World War, but then resumed as soon as peace was declared in 1945. So when, in 1952, I got a job as a trainee producer, British television had only ten years of practical production experience.

The programs were almost entirely live. Electronic recording was still decades away, so the only way we producers had of supplementing the pictures from the studio was with film. That cost money and we were seldom given enough to enable us to do so. This was not regarded as much of a limitation. On the contrary, both viewers and producers thought that the immediacy was the mediums main attraction. The events appearing on the screen were actually happening as viewers watched them. If an actor forgot his lines, then the prompt was audible. If a politician lost his temper, then all saw him do so and there was no chance for him to have second thoughts and insist that his incautious words were edited out.

Animal programs were already established in the schedules when I first started. They were presented by George Cansdale, the Superintendent of the London Zoo. Week after week, he transported some of the more reasonably-sized and amenable of his charges from Regents Park to Alexandra Palace and put them on a table covered with a doormat, where they sat blinking in the intense lights of the studio, while Mr. Cansdale demonstrated their anatomy, their bravery and their party tricks. He was an expert naturalist, marvelously adept at handling animals and persuading them to do what he wanted. Even so things did not always go as he might have wished. That was part of his popularity. They regularly relieved themselves on the doormat or, with luck, over his trousers. Occasionally they escaped and had to be fielded by one of the uniformed zoo keepers lurking in the wings ready for such an eventuality. Once a small African squirrel leapt from the demonstration table onto the microphone, hanging on a boom directly above. From there it scampered across the studio and found refuge in the ventilation system. It lived there for days, making occasional appearances in the dramas, variety shows and epilogues that continued to come from its studio. On a few memorable occasions an animal even managed to give Mr. Cansdale a nip. Such a moment was not to be missed and when he produced a particularly dangerous creature, like a snake, the nation held its breath.

Then, in 1953, a new kind of animal program appeared. A Belgian explorer and film-maker called Armand Denis, together with his glamorous British-born wife Michaela, came to London from Kenya to publicize a feature-length documentary they had made for the cinema called

Next page