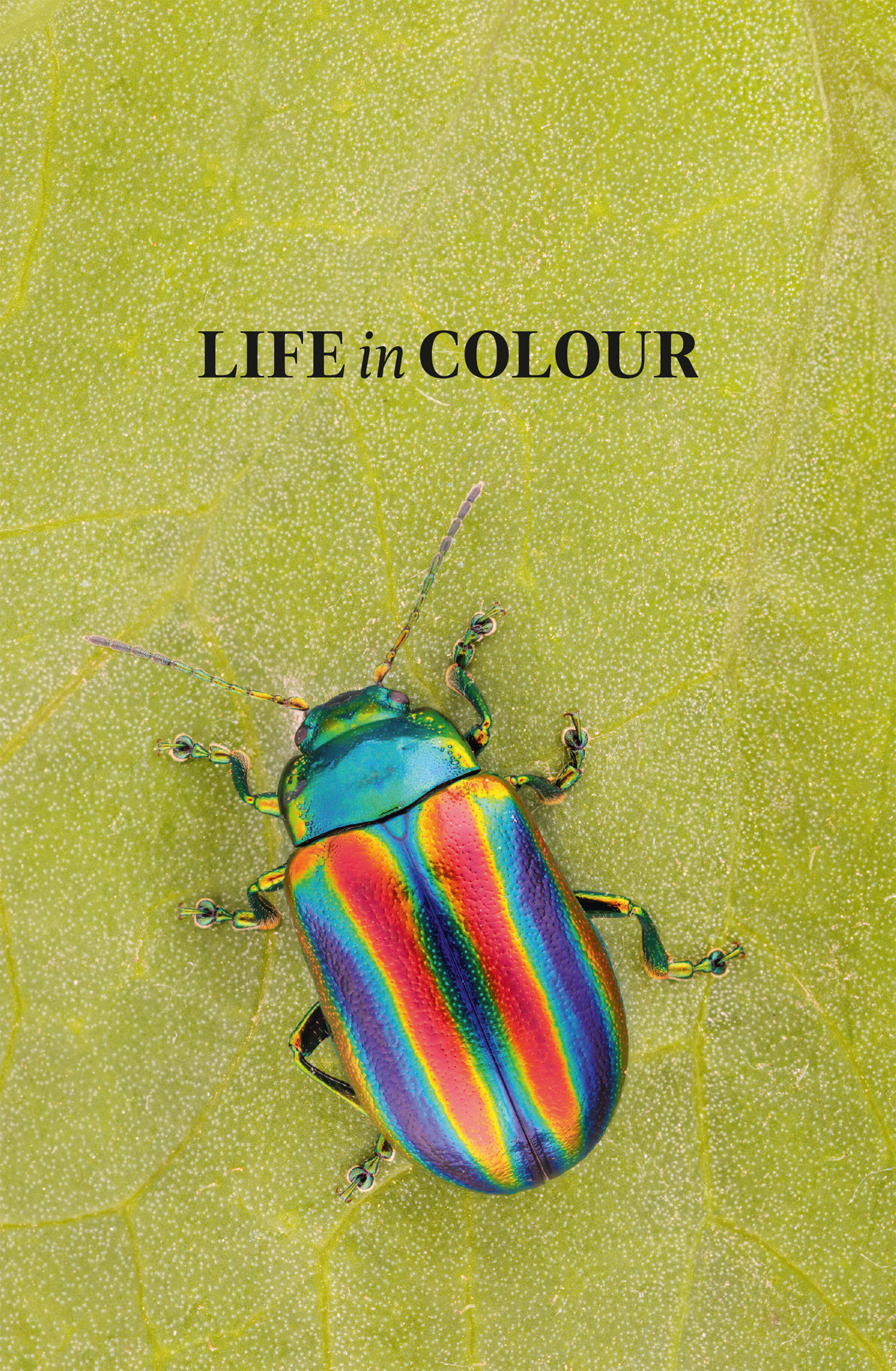

INTRODUCTION

In springtime, the British countryside is awash with colour: carpets of bluebells cover the woodland floor; brightly coloured robins, bullfinches and other birds dash back and forth to their nests; and insects, sporting a dazzling variety of hues, buzz all around. Colour is everywhere in nature, and it signifies the diversity of life better than almost anything else.

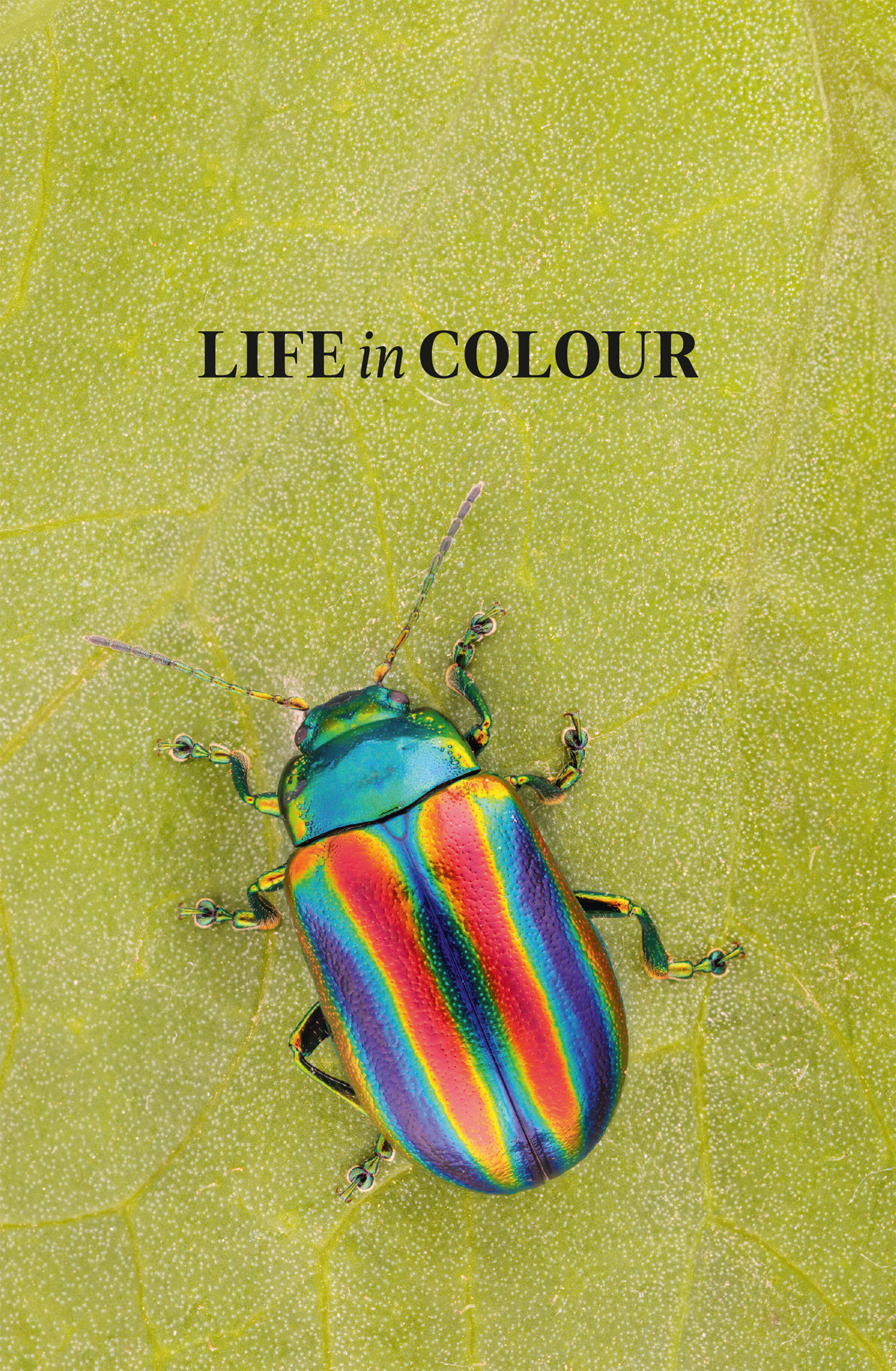

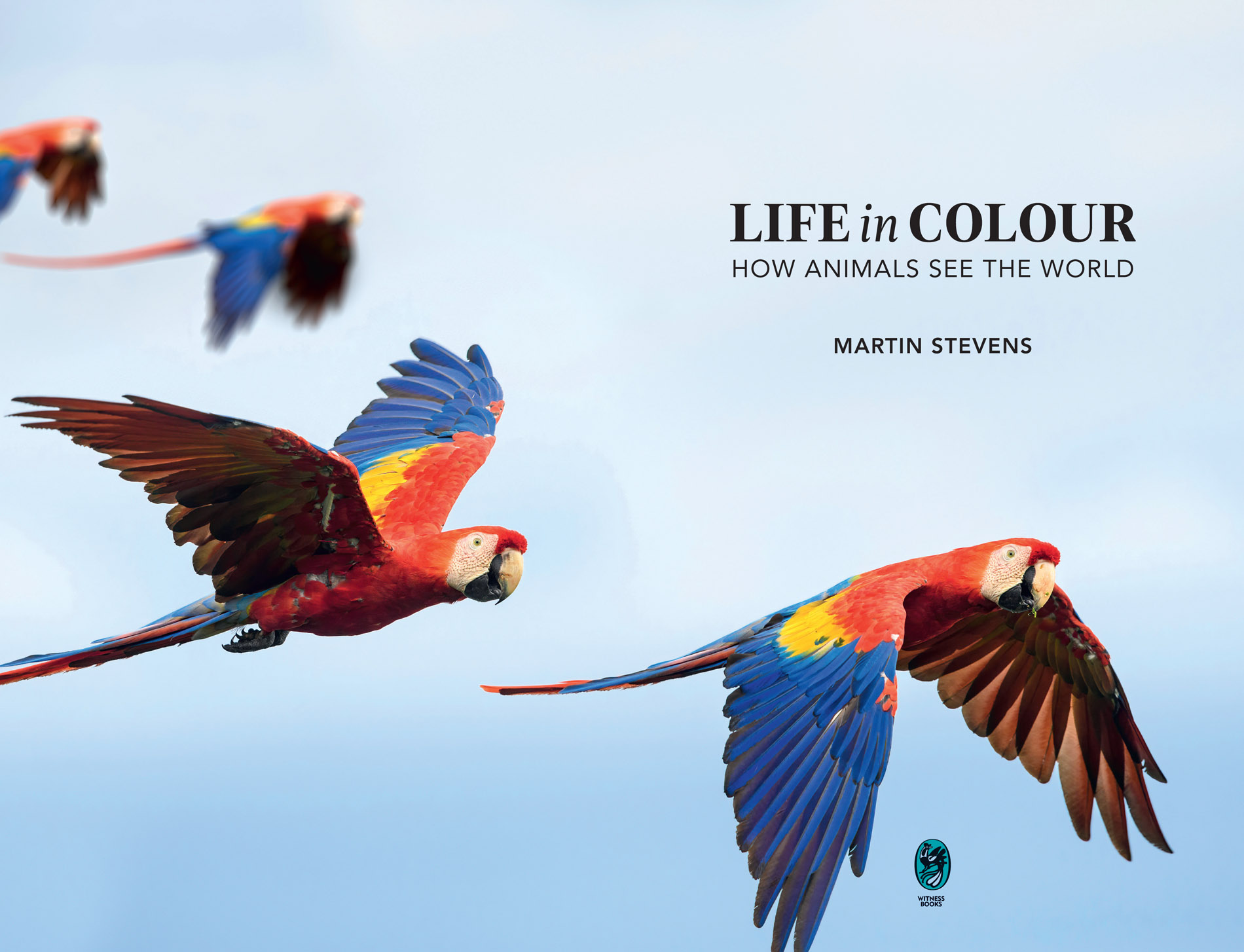

To us, the world can be a stunning place, but what is it like for other animals, and what functions does colour serve? The great variety of appearances in nature is no coincidence, for colour plays a critical role in practically every aspect of animal behaviour. It is key to attracting a mate, recognising individuals and species, deterring predators, and tricking others to do things that they might not otherwise intend.

The vibrancy of nature goes hand in hand with the variety of ways that animals perceive the world. For colour is not, as we often tend to assume, a property of an object itself, but rather a sensation imparted on animals as a consequence of how their vision and brain work. When we see a rainbow, we perceive a beautiful array of colours. This happens because white light from the sun passes through water droplets in the sky, which split the light into different wavebands, like a prism. Through the presence of several types of cells in our eyes the cones our vision is capable of capturing light of different wavelengths. Our brain colours different parts of the spectrum with a sensation of a given hue: red for longwave light, blue for shortwave light, and so on; but, the wavebands of light themselves have no intrinsic colour. Animals with different types of colour vision therefore should not see the world or, indeed, a rainbow quite like we do. Were a sea lion to gaze out of the water at a rainbow over the ocean, it would see no colour at all. A dog running along the beach would see the blue- and yellow-type hues, but not the pinks or reds that we do. On the other hand, a gull flying over the waves might see all the colours we sense, plus a variety more besides. Colour is in the eye of the beholder.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder not all animals can appreciate the colour of a carpet of bluebells in spring.

Some armour-plated molluscs have simple eyes distributed all over their body, like Ferreiras chiton from British Columbia.

The costumes of animals are rarely uniform blocks of a single colour. Instead, they come in all sorts of patterns and shapes, from the intricate eyespots on the wings of an emperor moth to the zig-zag markings on an adder. To see such patterns, animals must perceive spatial information in their environment, using sets of cells in their vision that form an image. This is normally undertaken using specific organs the eyes. Sure enough, eyes have evolved multiple times during the history of life and come in myriad forms. We are most familiar with the camera-type eyes of humans and other vertebrates, with a single opening and lens, where light is focused onto the back of the eye the retina, on which an image is formed. Yet eyes vary substantially. Insects, for example, possess an assortment of compound eyes, made up of thousands of tiny lenses, each projecting an image of a small part of the world onto the light-sensitive cells below. To them, the world looks rather more blurry.

Other types of vision are truly hard to comprehend. Small marine molluscs called chitons have hundreds of eyes all over their body, as do giant clams, with sparkling eyes distributed in lines along the outer mantle. Most bizarrely of all, some animals appear to be able to perceive crude differences in lighting, and even objects, without eye structures at all. They have sets of visual cells spread out over their whole body. Brittle stars have such an arrangement, and can orientate towards shelter in this way. Quite what the world looks like to these animals is hard to imagine.

With such an abundance of eyes to see the world, and so much variation in how creatures perceive light, it is, perhaps, unsurprising how widely colour patterns are used in nature, and the diversity in appearances they take unsurprising, but magnificent, for colour in nature is what helps animals to stay alive, find food and reproduce. Whats more, the diversity in how animals see their environment means that creatures living in the same place can perceive things quite differently. Groups of animals, for example, can communicate with one another using colours or patterns of light that are invisible to rivals or dangerous predators. Such private channels of communication can be hidden from us too, with their use of ultraviolet or polarised light. The natural world is one of technicolour, but each creature perceives only a snapshot of whats out there.

In Costa Rica, this red-eyed tree frog adopts green hues for camouflage and red for communication.

Not all colour in nature has a function, yet there is no doubt that the diversity in hues and patterns is frequently involved with a specific task, often in some form of communication. To begin with, colour plays a major role in enabling species to recognise one another, including to prevent mating with the wrong species, or even for animals to recognise specific individuals, be they friend or foe. Appearances are also of great importance to attract a suitable mate and convince a reluctant suitor that the bearer is up to standard.

On the other hand, colour can be central to signifying dominance and controlling rivalries, not just for mating, but in access to food or other resources. In many species, colour serves a critical function in defence, from warning predators that an animal is defended with toxins or spines, to camouflage, in order to hide in plain sight. Last but not least, colour is widely employed in deception, from sneaking past dominant rivals to get closer to potential mates, to tricking others into raising the young of another species as their own. Variety is the spice of life, and in nature that is exemplified perhaps no better than with the uses and diversity of colour.

Deceiving the eyes of both predators and prey, this satanic leaf-tailed gecko from Madagascar takes camouflage to its highest level.

CHAPTER ONE

FRIEND OR FOE

Our planets wildlife is spectacularly rich in colour witness the striking markings on a blue-ringed octopus or the vivid green body and bright red eyes of a tree frog but these colours are not there simply to look pretty. They serve a vital purpose, for colour is a key ingredient in the many remarkable and sometimes sinister ways that animals behave and how they influence the behaviour of others.

Communicating species identity is an important process in evolution, the inhabitants of coral reefs exemplifying the diversity of different colour patterns as well as any forms of life, not least in the myriad fish species that exist there. Decorated in yellows and blues, pinks and reds, reef fish dazzle scuba divers who descend into their vibrant world. Some fish peep out of crevices in the coral, while others brazenly swim in and around the habitat in great shoals. The most widely known, perhaps, are the clownfish. Of these, the most instantly recognisable species are the orange clownfish and the ocellaris clownfish, two species with the classic orange body and white stripes, often fringed with black outlines. They are colourful and charismatic (and make for good cartoon characters).

Next page

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder not all animals can appreciate the colour of a carpet of bluebells in spring.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder not all animals can appreciate the colour of a carpet of bluebells in spring.  Some armour-plated molluscs have simple eyes distributed all over their body, like Ferreiras chiton from British Columbia.

Some armour-plated molluscs have simple eyes distributed all over their body, like Ferreiras chiton from British Columbia.  In Costa Rica, this red-eyed tree frog adopts green hues for camouflage and red for communication.

In Costa Rica, this red-eyed tree frog adopts green hues for camouflage and red for communication.  Deceiving the eyes of both predators and prey, this satanic leaf-tailed gecko from Madagascar takes camouflage to its highest level.

Deceiving the eyes of both predators and prey, this satanic leaf-tailed gecko from Madagascar takes camouflage to its highest level.