First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Gavin Evans 2017

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-690-4 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-691-1 in ebook format

Follow us on Twitter @OMaraBooks

www.mombooks.com

Cover design by Ana Bjezancevic

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publisher, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of the work.

To my daughters Tessa and Caitlin: it would be an awful clich to say you put colour in my life, but Ill say it anyway.

CONTENTS

I f pupils were concentrating at school they might have learnt the mnemonic Roy G Biv, one way of teaching children the usual order of colours of the rainbow red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet just as some British children learn the alternative Richard of York gave battle in vain. In India pupils learn VIBGYOR, which is the reverse order of Roy G Biv. Either way round, no purple and most definitely no pink.

And yet, are red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet really the correct colours of the rainbow? Well, yes, and one can add to the list or subtract, as long as one doesnt throw in grey or gold or brown, or pink, for that matter. It all depends on where one lives, or when one lived, because the received colours of the rainbow have changed according to culture and over time.

Let us go back to the man who invented what became Roy G Biv: perhaps the most remarkable scientist of them all, Isaac Newton. Along with his discoveries on the laws of planetary motion and of gravity, and his co-discovery of calculus and his huge contribution to developing the scientific method, he was obsessed with light and colour. This prompted one of his most famous experiments (in his rooms, during the Great Plague, when the university was closed). Using a partition board with a pinhole in it and a glass prism, he observed how white light can be broken into the colours of the rainbow.

As Newton explained it: In a very dark chamber, at a round hole, about one-third part of an inch broad, made in the shut of a window, I placed a glass prism, whereby the beam of the suns light, which came in that hole, might be refracted upwards toward the opposite wall the chamber, and there form a coloured image of the sun.

He showed that white light is the combination of the full colour spectrum. In his book Opticks (1704), he explained how these colours comprise light rays that bend, or refract, at different angles when passing through a prism, so the colours separate. The ray that bends the most is violet, with the shortest wavelength, and the least is red, with the longest wavelength. In the middle is green. Crucially, he reversed the experiment too, demonstrating that the spectrum of colours can be reassembled into white light.

A century on, in a book titled Theory of Colour, the great German thinker Johann von Goethe described Newtons idea that white light was a combination of all the colours as an absurdity and he moaned about people parroting Newtons idea in opposition to the evidence of their senses. What Newton understood, and Goethe failed to grasp, was the difference between the colours of the paintbox and those of light. Mix the pigments of the artists palette together and one gets a very dirty grey-brown. But when considering light, it all changes. Spin a colour wheel fast enough and it will appear white.

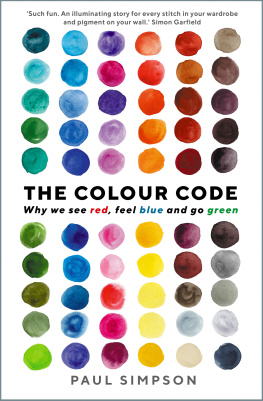

Sir Isaac Newton examining the nature of light with the aid of a prism. This allowed him to see that white light is comprised of multiple colours, what we now call the colours of the spectrum.

There are other differences, too. In the paintbox the primary colours are red, blue and yellow, with all others a combination of these. With light, the primary colours are green, blue and red. Mix all three equally and one gets white. Mix varying ratios of these and one can get any other colour in the rainbow. Every picture or illustration we see on our televisions or our laptops or smartphones is the product of tiny green, blue and red dots.

Despite his scientific and mathematical genius, Newton was very much a man of his time, one whom John Maynard Keynes called the last of the magicians. When taking breaks from advancing science and mathematics, and from hanging counterfeiters and excoriating his scientific rivals, Newton spent his time studying the Holy Trinity, the occult and searching for the philosophers stone. He had a mystical fondness for the supposedly magical properties of the number seven, which he also saw as the prime number of nature (the seven notes of the Western musical scale, the seven planets of the solar system, and so on).

After some prevarication, Newton opted for seven colours of the rainbow, rather than the previous five or six (the colours he added were orange and indigo). Really, there are no pure colours in a rainbow, as such, for they all blend into one continuous spectrum. We might see seven but in reality there is not a delineated gradient, which means the boundaries are blurred and the divisions arbitrary. Interestingly, the colour orange did not exist in Europe until the orange fruit was introduced. Prior to its introduction, orange objects were described as gold or golden, which is why we have goldfish instead of orangefish. In fact, tomatoes were originally called golden apples, too.

When we see the full range of visible light waves together, our eyes and our brains say white but when some of those wavelengths are missing we see them as colours. More accurately, objects absorb different parts of the white light spectrum, so we see those parts that are reflected. But the colours the human eye chooses to see and how it chooses to see them varies from one culture to another and even from one individual to another.

In English indigo is really another word for dark blue and violet is often used as an alternative word for purple. Newtons blue could also be called turquoise, and so on. We all see the same range of colours when we look at the rainbow, but how we identify them differs. According to the philosopher Xenophon, the Ancient Greeks identified only three colours in the rainbow red, yellow and purple. Ancient Arab tradition also agreed on three but they used red, yellow and green.

Part of our colour perception relates to the genes we happen to inherit individually. Yet rather more important are cultural differences, which have been influenced by the way our societies have used colour over time and the number of colours in our cultural palette has expanded as we have found new ways of capturing the hues of nature in paints, dyes, tints and pigments, and in how we use colours and patterns to adorn ourselves, our homes, our places of work and our possessions.