To the men of Hezbollah and Jamiat-i-Islami, particularly Nebi Mohandaspoor, I owe my sincerest gratitude for allowing me to share their lives. To my family and especially my mother for enduring the months of not knowing; to Sue and Brian Shoosmith for their friendship, outrageous hospitality and the loan of a Northamptonshire cottage in which this book first took shape; to all my friends in New Zealand and England for their constant encouragement; my appreciation extends beyond these few words.

To Elisabeth

With a Heart of furious fancies,

Whereof I am Commander.

With a burning spear and a horse of air,

To the Wilderness I wander.

With a knight of ghosts and shadows,

I summoned am to Tourney.

Ten Leagues beyond the Wide Worlds end,

Methinks it is no Journey.

Tom-a-Bedlam

CONTENTS

Guide

Auckland, New Zealand, September 2001

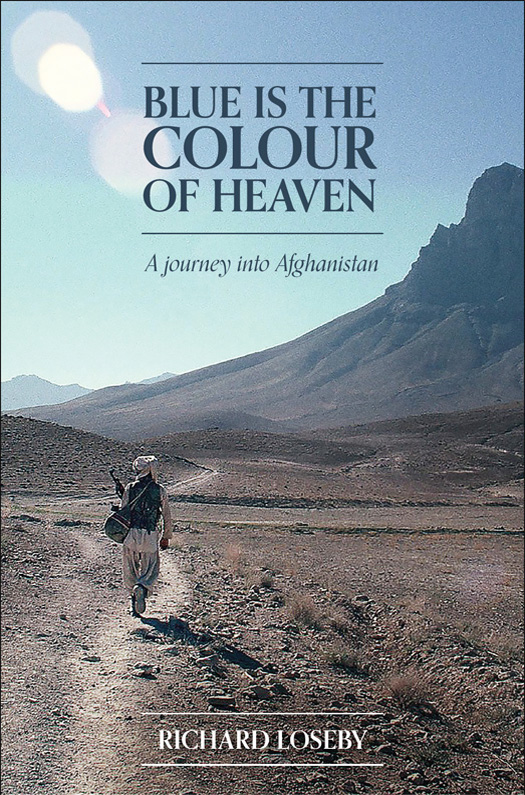

What colour is it in heaven, Daddy?

I look up from the newspaper that is plastered with photographs of the World Trade Centre collapsing under the weight of terrorism. My bright-eyed son Thomas is looking at me on the window seat with all the curiosity of youth, clutching a Thunderbirds toy and watching CNN from the sofa. He returns to the images that depict scenes of more devastation. I cringe because I hadnt realised the TV was still on. Death pervades the sitting room and Im the guilty parent, corrupting my childs innocence. I reach for the remote to let normality resume. The thick black smoke clears and the sun suddenly shines through the garden doors. Tangled metal is replaced by twisted climbing roses and a lemon tree.

Come on, Tom, I say, trying to change the subject and putting away the paper. Lets go find Isobel.

He gets off the sofa and on the way past the piano bumps his head on the thick wooden leg. Not badly, but its enough to cause a tear or two. I crouch down and place my hand on the growing lump, willing it to go away.

The little cottage we live in is growing smaller as the children get bigger. One of these days were going to have to move somewhere that doesnt present as many obstacles to anyone under three feet tall. Old Broadwood grand pianos are beautifully made, but they tend to take up a bit of room. Wed be more comfortable in a villa; one with double bay windows and a return verandah wide enough for scooters and skateboards.

Better? I ask, taking my hand away.

He gives it a good rub and nods back. Theres a red mark, but the bump has receded.

If only the pain of the last few weeks could be so easily remedied, then perhaps Afghanistan might have been spared the horror of being dragged into yet another war, this time not one of its own making. The phone had already run off the hook withfriends asking how I felt about the New York terrorists, the Taleban government, Osama bin Laden. Each time I had pointed out that people like this did not represent the average Afghani; in fact far from it most of them werent even Afghans. The people of Afghanistan were proud and honourable, no more bent on the destruction of Western civilisation than you or I. They just wanted to go back to their lives, I would say. After over two decades of conflict they had grown tired, fighting off an invader who lurked outside the walls. No wonder they had been overtaken so easily by the one from within.

I turn back to my boy.

Well, says Tom, not prepared to wait any longer for an answer to his question. I hope its a really pretty colour. Sort of like... blue maybe.

Could be, I reply. It could well be.

In Sofia, with the British Ambassador and his wife, I was invited to join a final dinner party on the eve of their retirement. The other guests were a mixture of British embassy people and high-ranking Bulgarian officials, including an old bull-necked General and a young, attractive interpreter. The Bulgarians, however, were the dominant force, and their ruddy faces beamed in anticipation of the excellent meal to come.

The residence was all elegant staircase, creaking floorboards, long echoing passages and high-ceilinged rooms, richly decorated with the ambassadors personal collection of objets dart; souvenirs from his other postings. He and his wife, who were old friends of my family, had lived all round the world but Sofia was their final assignment. Now they were about to exchange the big house for a small cottage somewhere deep in the English countryside. It was a hectic time, but even so, on hearing that I was passing through by train from London, they had generously invited me to stay.

It was February. Snow was drifting down outside and collecting on the window-sills, while in the dining room a log fire crackled away in the grate, burning brightly and casting shadows out across the floor. I sat half way down the long table, opposite the General who, having left his gold braid behind, wore a suit instead of a uniform. He looked smart in a military way, but not comfortable.

I am told you are a traveller, he growled. It is a profession?

Of sorts.

Do you travel in my country now?

Not this time, I replied. Im headed further east.

He interrupted with a click of his tongue.

Muslims, he said disparagingly. I do not care for them much, and he looked away to eye up the pretty interpreter.

The man on my left was Bulgarian also, of slender build, with thick black Balkan hair and a jutting chin. He was younger than the others, in his early thirties perhaps, and had his eye on the girl as well. But for the moment he wanted to hear more of my plans and took up the conversation where the General left off.

You have heard the news of course, about Iran.

Less than two days before, Irans Ayatollah Khomeini had slapped a fatwa on the head of Salman Rushdie for his book The Satanic Verses. Now it seemed the whole world had gone mad. Muslim demonstrations in Londons Regents Park, book burnings in Pakistan, idle threats from far-flung Islamic countries and the breaking off of diplomatic relations between Britain and Iran. My chances of travelling any further than Turkey, of getting into Iran as I had planned for months, were now severely jeopardised.

Im hoping itll die down quickly, I said.

He nodded doubtfully and frowned at his empty wine glass, willing one of the staff to notice. Then he looked up and asked, abruptly, Why do you want to go to Iran? The border is closed. No one can get through.

He was right, of course. The entire country was a closed shop had been ever since the Islamic revolution in 1979, when the corrupt regime of the Shah had been finally deposed by the return of Ayatollah Khomeini. I could still remember the television news bulletin showing the Ayatollah arriving at Teheran airport on an Air France flight from Paris. There was little sign then of the bloodshed that would soon follow: the enforcement of Koranic law, the eight long years of war with Iraq, the purges and pogroms against those who did not conform. Since then, the war had ended but nothing else had drastically changed.

I want to find out something, I said. Or someone, perhaps.

An Iranian?

Not exactly, I replied.

You are not sure?