Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR DEVON,

you are my reason for everything.

Contents

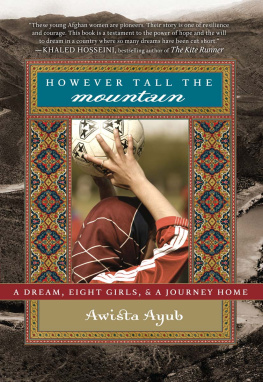

No matter how high the mountain, there is always a road.

AFGHAN PROVERB

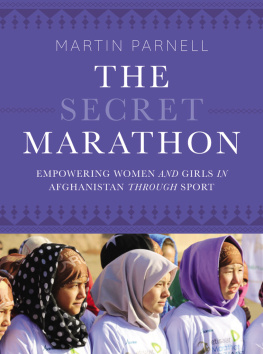

Single-Speeds in a War Zone

Afghanistan 2009

This is a bad idea.

Breathe. Just breathe. Steady.

Just let go of the brakes and ride through. You got this. You know how to ride a bike.

Damn, these rocks are sliding! Worst trail ever. Dont crash. Please, please, please. Not here.

The mountainside was more rock strewn than it had appeared. These barren slopes were not like those I was used to biking in Colorado. Devoid of trees, the slopes looked like someone had dynamited the mountain and left the rubble where it had fallen. My bike was rolling down what had started out as a narrow goat path farther up the mountain. Almost immediately the path disappeared, and there was no clear way up or down, just rocks in all directions.

The ground slid, and small stones sprayed underneath my tires. I tensed.

Whose idea was this?

Yours, my brain replied.

Theres no path!

Yeah, well, there could be land mines if you ride off the path.

My heart pounded. I focused downhill. Picking a line through the rubble, I steadied my nerves and took a deep breath. I gripped my handlebars and tried to keep my bike upright. The school and the open courtyard sat at the base of the mountain, a small white oasis in the sea of brown. I shifted my weight over the back tire. I let go of the brakes and let the speed take me through. Shades of brown rushed by in a blur as I picked up speed. I bent my elbows deeper to allow my arms to absorb the bouncing. My teeth chattered with the vibrations. My tires slid more than they rolled, searching for solid ground.

Youre almost down. Relax. Breathe. Just ride. You know how to do this. Breathe! Dust stung my eyes. My hair was sweaty and plastered to my head under my checkered head scarf. My heart pounded even harderwhether from fear, exertion, or the layers of clothing I wore that felt like a sauna, I wasnt entirely sure.

Suddenly the tires stopped sliding and I was on level, solid ground. The mountain had spat me out alive. As if a mute button was released, sound flooded my ears: cheering. Six hundred boys were cheering. I looked up for the first time since Id started my descent and smiled in relief through the cloud of dust. Six hundred Afghan boys smiled back. And one threw a rock. Six hundred to one? Ill take those odds.

Travis was smiling at me from behind the sea of faces. Nice job, mate. They loved it. They cant believe you didnt crash. It would have been more entertaining if you had, though.

I wanted to punch him, but in Afghanistan women dont punch men, playfully or not. But, in Afghanistan, women also dont ride bikes.

In a remote village, in the heart of the Panjshir mountains, six hundred boys, their teachers, and a few random villagers who wandered over, had just watched a woman ride a mountain bike behind their schoolyard. This was the first time any of them had seen a girl ride a bike. What they maybe didnt realize was that they had just witnessed the first time any woman had mountain biked in Afghanistan.

* * *

I didnt go to Afghanistan planning to ride a mountain bike. Does anyone travel to a war zone and say to themselves, I wish I had remembered to pack my mountain bike, helmet, and lycra! This would be an awesome place to ride. No, they probably dont.

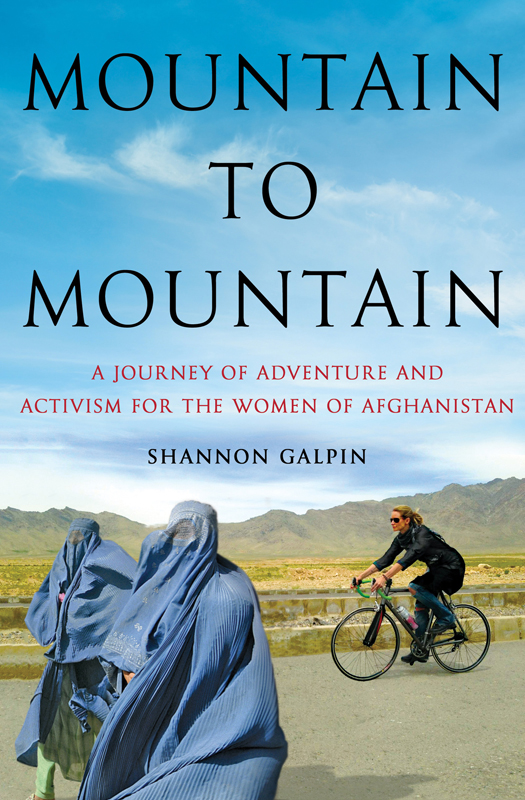

But on my fourth trip in 2009, I decided to bring my tangerine Niner 29er single-speed and challenge the gender barrier that prevents women from riding bikes. Afghanistan is one of the few countries in the world that doesnt allow its women or girls to ride. But Im not Afghan. Standing tall at five foot nine, with long blond hair, I am clearly not a local. While many back home assume being so obviously a foreigner is an inherent risk, it has become my biggest asset. A foreign woman here is a hybrid gender. An honorary man. A status that often allows me a unique insight into a complicated region.

Afghan men recognize me as a woman, but as a foreign woman. I am often treated as a man would be. I sit with the men, eat with the men, dip snuff with the men. I have fished with them. They have let me ride buzkashi horses. All while their women are often shut away in the family home, not to be seen or heard. Im in a fascinating position, being able to speak freely with the men who make the decisions, while having full access to the women because, despite my honorary male status, I am a woman. It allows me a unique insight into both sides of the gender equation, which often have extremely divergent perspectives.

I have discussed this with other foreign women I know who live and work in Afghanistan and Pakistanjournalists, photographers, writers, and aid workersand they all have the same experience. They are most often met with curiosity and a willingness to talk as equals. Unfortunately, too often they are also faced with overly flirtatious Afghan men. More than once I have been groped in close quarters by a man who thought he could get away with it because Im American. The assumption that American women are promiscuous is an unfortunate and deep-seated stereotype that has preceded me in many countries throughout the Middle East and Central Asia. It has led to more than one unwanted advancement, and the occasional marriage proposal. Thanks to globalization, the only consistent exposure many cultures have to American women is through movies, television, and music videos. Do we realize that our gender is judged on the standards of rap videos, Miley Cyrus, and the Kardashians?

Shaima, a friend I met on my first visit, illustrated the gender issue succinctly. Shaima was an American from Boulder, Colorado, and was half Afghan and half Costa Rican. She was in the country for several months to work with an Afghan nonprofit. Because she looked Afghan, she often encountered men who wouldnt speak to her. She would be at a meeting discussing next steps with the program they were working on, a program she was in charge of, and Afghan men often wouldnt shake her hand or speak to her directly. They would speak to her male colleagues as if she were invisible.

Over time I began to embrace the access that my honorary male status allowed. I was frustrated by the double standard, but I soon recognized the opportunity to challenge the gender barriers as a foreign woman in ways that might not have been tolerated if I were an Afghan woman. My theory was that beyond illustrating what a woman was capable of to Afghans, I would also be able to experience Afghanistan in a way few others had before me. By sharing my experiences and stories back home, perhaps I could challenge perceptions in both countries.

So it was on October 3, 2009, that I first put the rubber side down on a dry riverbed in the Panjshir Valley. It was part of the small but strategic Panjshir province, its mountains so steep that theyd kept the Taliban outone of the few areas able to do so.