Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

PENGUIN

an imprint of Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited

Canada USA UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

First published as Wir sind noch da!: Mutige Frauen aus Afghanistan by Elisabeth Sandmann Verlag, Germany in 2021

Published in 2022 in Penguin paperback by Penguin Canada

Simultaneously published in the United States by Plume, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

Copyright 2021 Elisabeth Sandmann Verlag GmbH

constitute an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

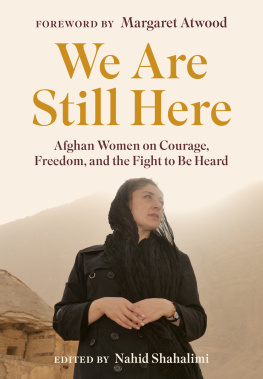

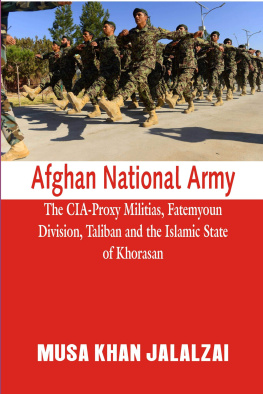

Title: We are still here : Afghan women on courage, freedom, and the fight to be heard / Nahid Shahalimi ; foreword by Margaret Atwood.

Other titles: We are still here (2022)

Names: Shahalimi, Nahid, 1973- editor. | Atwood, Margaret, 1939- writer of foreword.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20220147078 | Canadiana (ebook) 20220147256 | ISBN 9780735246003 (softcover) | ISBN 9780735246010 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: WomenAfghanistanBiography. | LCSH: WomenAfghanistanSocial conditions. | LCSH: Womens rightsAfghanistanHistory21st century. | LCSH: AfghanistanHistory2001-2021. | LCSH: AfghanistanHistory2021- | LCSH: AfghanistanSocial conditions21st century. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC HQ1735.6 .W4 2022 | DDC 305.409581/0905dc23

Book design by Jennifer Griffiths

Cover image by Nahid Shahalimi

a_prh_6.0_140638707_c0_r0

To my daughters, Ila and Mina: I hope we leave even better paths for you to walk on than the ones paved for us.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY MARGARET ATWOOD

A LONG , LONG time ago nowin 1978, when people now forty years old had not yet been bornGraeme Gibson and I set out to travel around the world. Our destination was the Adelaide Festival in Australia, but you could get a round-the-world ticket that allowed you to stop along the way, so that is what we did. We had our eighteen-month-old daughter with us and felt that a single flight to Australia would be much too long on a plane for her.

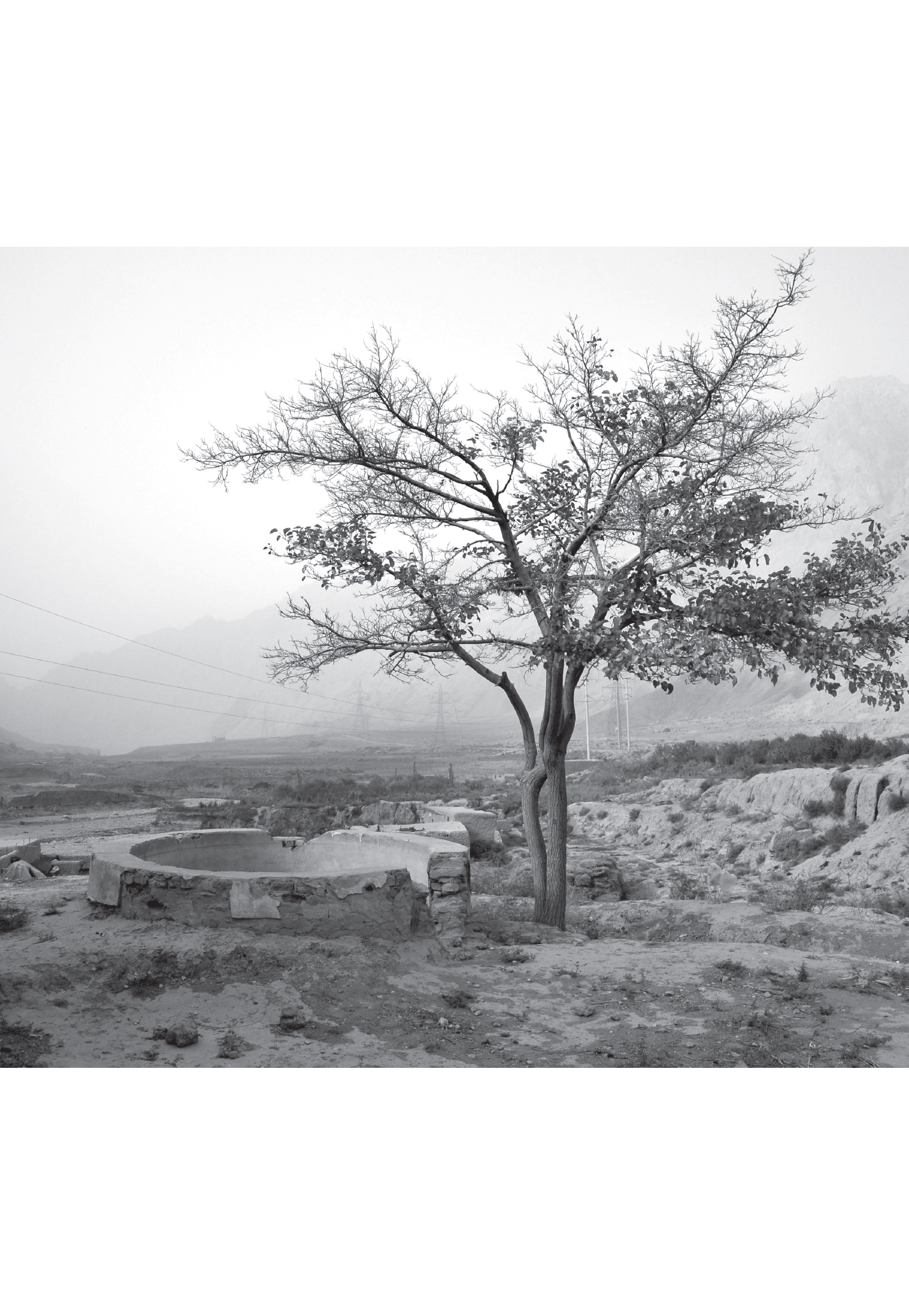

The decision to stop in Afghanistan was mine. From the little I knew of history, I had been fascinated with it from afar. No foreign invader had ever succeeded in holding it long, including the British. Alexander the Great said, famously, that Afghanistan was very easy to march into but very difficult to march out of. The Russians were shortly to have the same experience, followed some decades later by the Americans. Why? Possibly the extremely challenging terrain, coupled with the ferociously independent spirit of the people.

Before we left, my father said, Dont go. Theres about to be a war. How did he know? Six weeks after our visit, President Daoud Khan and almost his entire family were assassinated, ushering in the forty-plus years of warfare we have been witnessing ever since. We were lucky to have seen this spectacularly beautiful country just before it began to be torn apart.

Some say that Daoud Khans encouragement of education and jobs for women was one of the reasons for his assassination. Whatever the truth may be, the position of women in Afghanistan made a deep impression on meparticularly their virtual invisibility in public spaces. Needless to say, this invisibility was one of the many influencesfrom both the past and the present, and from around the worldon my construction of womens roles in the Republic of Gilead in The Handmaids Tale. I began writing that book in 1981, and it was first published in 1985, so you can see that my proposal of an American theocracy enforcing very limited roles for women came soon after my Afghanistan visit.

But what nownow that a puritanical theocratic regime has once more gained power in Afghanistan? Women who have been very activeas teachers, as scientists, as thinkers, as health workers, as creatorswill be forced back into invisibility. They will be told they should not be allowed to have an education, becausehere you may supply one or several of the answers that have been given, in many countries, in many times. Those answers have included womens incapacity for higher thought, their proper role as the bearers of children and the servants of the family, and so forth. Some in nineteenth-century Britain maintained that if women became educated, too much blood would flow to their brains, and their child-bearing organs would shrivel up. There has been no end of reasons, but none of them stands up to scrutiny. Lets say that one of the true reasons has to do with power and control, and the encouraging of a malignant side of human nature: the pleasure some take in inflicting pain on others.

Many women in Afghanistan have already disproven the idea that women cannot teach, learn, research, invent, cure, and create. Perhaps they will be forced into the shadows, hidden from view, their talents made unavailable to their country and their communities, but what they already know cannot be erased. I cant predict the future: I dont know how this amputation of women and their skills will affect Afghanistan. Perhaps younger women will be more despairing, as they did not live through the time when women moved from invisible to visible. Perhaps older women will be more tenacious, believing that what has been accomplished before can be accomplished again. In our strange and desperate times, plagued by a pandemic and by the brutal effects of the climate crisis, nothing is predictable. But as the Afghan women themselves have said, We are still here. That in itself is a considerable statement: over forty years of turmoil and destruction, of rebuilding, of more destruction, they have been through so much.

A country without any women at all cannot exist for long. No matter how much a regime may hate and punish women, it cant do without them entirely. But what sort of women? We shall see.

INTRODUCTION

BY NAHID SHAHALIMI

FOR AS LONG as I can remember, we have not had time to mourn. One disaster has succeeded another. We have lost loved ones, our homeland, our freedoms, and our hopes. Now an entire nation and its youth are being denied what they require to even feed themselves and their families.

My Afghan friends and I do not have time to mourn because we want to help those who remain in our homeland and give voice to those who go unheard and may never be heard again. Radical repressive forces are now at work in Afghanistan, and this is of significant concern to all people of the world, but especially to women. Although Afghanistan is physically distant from Germany, which I call home today, radical ideas know no borders.