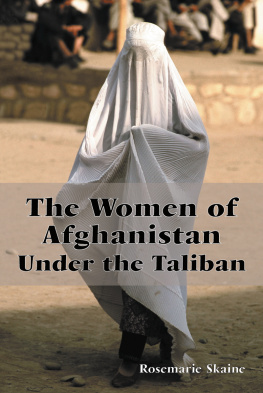

A T THE HEAD of the Khyber Pass, when we reached the border with Afghanistan at Torkham, our car stopped short of the Taliban checkpoint. Before getting out of the car, my friend Abida helped me to put the burqa on top of my shirt and trousers and adjusted the fabric until it covered me completely. I felt as if someone had wrapped me in a bag. As best I could in the small mountain of cheap blue polyester, I swung my legs out of the car and got out.

The checkpoint was a hundred yards away, and I stared for a moment at my homeland beyond it. I had been living in exile in Pakistan for five years, and this was my first journey back to Afghanistan. I was looking at its dry and dusty mountains through the bars of a prison cell. The mesh of tiny holes in front of my eyes chafed against my eyelashes. I tried to look up at the sky, but the fabric rubbed against my eyes.

The burqa weighed on me like a shroud. I began to sweat in the June sunshine and the beads of moisture on my forehead stuck to the fabric. The little perfumemy small gesture of rebellionthat I had put on earlier at once evaporated. Until a few moments ago, I had breathed easily, instinctively, but now I suddenly felt short of air, as if someone had turned off my supply of oxygen.

I followed Javid, who would pretend to be our mahram, the male relative without whom the Taliban refused to allow any woman to leave her house, as he set out for the checkpoint. I could see nothing of the people at my side. I could not even see the road under my feet. I thought only of the Taliban edict that my entire body, even my feet and hands, must remain invisible under the burqa at all times. I had taken only a few short steps when I tripped and nearly fell down.

When I finally neared the checkpoint, I saw Javid go up to one of the Taliban guards, who was carrying his Kalashnikov rifle slung jauntily over his shoulder. He looked as wild as the Mujahideen, the soldiers who claimed to be fighting a holy war, whom I had seen as a child: the crazed eyes, the dirty beard, the filthy clothes. I watched him reach to the back of his head, extract what must have been a louse, and squash it between two fingernails with a sharp crack. I remembered what Grandmother had told me about the Mujahideen: If they come to my house, they wont even need to kill me. Ill die just from seeing their wild faces.

I heard the Taliban ask Javid where he was going, and Javid replied, These women are with me. They are my daughters. We traveled to Pakistan for some treatment because I am sick, and now we are going back home to Kabul. No one asked me to show any papers. I had been told that for the Taliban, the burqa was the only passport they demanded of a woman.

If the Taliban had ordered us to open my bag, he would have found, tied up with string and crammed at the bottom under my few clothes, ten publications of the clandestine association I had joined, the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan. They documented, with photographs that made my stomach churn no matter how many times I looked at them, the stonings to death, the public hangings, the amputations performed on men accused of theft, at which teenagers were given the job of displaying the severed limbs to the spectators, the torturing of victims who had fuel poured on them before being set alight, the mass graves the Taliban forces left in their wake.

These catalogs of the crimes perpetrated by the Taliban guards regime had been compiled on the basis of reports from our members in Kabul. Once they had been smuggled to the city, they would be photocopied thousands of times and distributed to as many people as possible.

But the Taliban made no such request. Shuffling, stumbling, my dignity suffocated, I was allowed through the checkpoint into Afghanistan.

As women, we were not allowed to speak to the driver of a Toyota minibus caked in mud that was waiting to set out for Kabul, so Javid went up to him and asked how much the journey would cost. Then Abida and I climbed in, sitting as far to the back as we could with the other women. We had to wait for a Taliban to jump into the minibus and check that there was nothing suspicious about any of the travelers before we could set off. For him, even a woman wearing white socks would have been suspicious. Under a ridiculous Taliban rule, no one could wear them because white was the color of their flag and they thought it offensive that it should be used to cover such a lowly part of the body as the feet.

The longer the drive lasted, the tighter the headband on the burqa seemed to become, and my head began to ache. The cloth stuck to my damp cheeks, and the hot air that I was breathing out was trapped under my nose. My seat was just above one of the wheels, and the lack of air, the oppressive heat, and the smell of gasoline mixed with the stench of sweat and the unwashed feet of the men in front of us made me feel worse and worse until I thought I would vomit. I felt as if my head would explode.

We had only one bottle of water between us. Every time I tried to lift the cloth and take a sip, I felt the water trickle down my chin and wet my clothes. I managed to take some aspirin that I had brought with me, but I didnt feel any better. I tried to fan myself with a piece of cardboard, but to do so I had to lift the fabric off my face with one hand and fan myself under the burqa with the other. I tried to rest my feet on the back of the seat in front of me so as to get some air around my legs. I struggled not to fall sideways as the minibus swung at speed around the hairpin bends, or to imagine what would happen if it toppled from a precipice into the valley below.

I tried to speak to Abida, but we had to be careful what we said, and every time I opened my mouth the sweat-drenched fabric would press against it like a mask. She let me rest my head on her shoulder, although she was as hot as I was.

It was during this journey that I truly came to understand what the burqa meant. As I stole glances at the women sitting around me, I realized that I no longer thought them backward, which I had as a child. These women were forced to wear the burqa. Otherwise they faced lashings, or beatings with chains. The Taliban required them to hide their identities as women, to make them feel so ashamed of their sex that they were afraid to show one inch of their bodies. The Taliban did not know the meaning of love: women for them were only a sexual instrument.

The mountains, waterfalls, deserts, poor villages, and wrecked Russian tanks that I saw through the burqa and the mud-splattered window made little impression on my mind. I could only think ahead to when my trip would end. For the six hours that the journey lasted, we women were never allowed out. The driver stopped only at prayer time, and only the men were allowed to get out of the minibus to pray at the roadside. Javid got out with them and prayed. All I could do was wait.

K ABUL WAS ALWAYS more beautiful in the snow. Even the piles of rotting rubbish in my street, the only source of food for the scrawny chickens and goats that our neighbors kept outside their mud houses, looked beautiful to me after the snow had covered them in white during the long night.