For Tom and Issie

As for me, I am tormented by an everlasting itch for things remote.

Herman Melville, 1844

CONTENTS

Guide

B EIJING , 1949

He Zizhen, third wife of Chairman Mao, clasped and unclasped her hands anxiously as she peered from the windows of Chinas Communist Party headquarters. A grey winter sky hung low over Beijings rabbit warren of ancient cobbled lanes and humble timber dwellings, where the inhabitants of her husbands new China huddled round mah jong tables and desperately gambled for scraps of food. Loyalists of the former ruler, General Chiang Kai-shek, had already been arrested and their bodies hung lifelessly from street posts and city gates, swaying in the icy wind that blew down from the Mongolian steppe. A wary population pointed fingers of suspicion in any direction, seeking to avoid becoming the focus of the Communist Red Army guards. They had good reason: the guards were young radicals, fired up by Maos speeches, which denounced the old ways and promised them a brighter future in which their militant voices would be heard. These were dangerous times. Close neighbours and even family members looked nervously at each other over their half-empty rice bowls.

Not far away was the Forbidden Palace: dormant, emperorless, devoid of the officials, concubines and eunuchs that once inhabited its many thousands of rooms. Little did He Zizhen care for history. What mattered most was the present, and that her world had now shifted on its axis in the most terrible of ways. Her husband Mao Tse-tungs infidelity with the actress Lan Ping had long since destroyed their marriage, but now word had come of something far worse. Her beloved sister had disappeared in a province many thousands of kilometres away to the south, while on a mission to look for the young son He Zizhen had been forced to give up years before, at the beginning of what had become known as the Long March. A father who cared more for power than his progeny, Mao had forbidden He Zizhen to travel there herself. Now, with her marriage over, and her life unravelling, she was tortured by guilt, grief and not knowing.

Within the tight circle of Maos advisors, from which she was increasingly excluded, she could hear whispering that a madness had overtaken her. The murmurings were becoming stronger too, counselling him that there were other places better able to care for her, places far away and out of sight that could tend to her worsening mental condition. Perhaps they were right. The loss of her child, her Little Mao, whom she loved with all her might and feared she would never hold again, was a weight on her heart that was beyond unbearable. Whatever strength of hope she had left now deserted her. Whatever life shed imagined for them all was gone.

Her husbands officials said her son was a boy of China now: not hers or any other individuals, but a citizen who would grow to help make this new nation great through hard work on the land. It would be a noble life, a victorious existence, not in the arms of his birth mother, but in the warm embrace of Mother China.

He Zizhen, you should rejoice and be proud, they said.

But whenever she tried to feel that way, the tears would come and not stop. And nothing could be done to stem their flow.

I T WAS WHILE TRAVELLING THROUGH THE MORE REMOTE REGIONS of western China, towards the end of 1989, that I first heard the strange story of Little Mao. I had entered the country from Northern Pakistan after travelling by foot across Afghanistan from Iran, arriving on the Chinese border just before an early snowfall closed the towering Khunjerab Pass. From there I had made my way to the horse-trading town of Kashgar in Xinjiang province, and an eventual encounter one Sunday with Mr Wong, the local schoolteacher.

Mr Wong was a thin, wiry figure in his thirties who wore grey suit trousers and a white business shirt through which a singlet was clearly visible. On his feet were sandals that showed off an assortment of unsightly toenails. He hated Kashgar and thought the local children dirty.

Uighurs, he said disparagingly, referring to the local population of ethnic Muslims. They use their hands to wipe their bottoms.

His real home was thousands of kilometres away to the east in Hunan province, but Mr Wong had upset a Communist Party official there and had found himself relocated to the far west for the good of the state. I asked him what he had done to deserve such treatment and initially he wouldnt say, but the loose tongue that had got him into trouble in the first place was still active in his mouth. Over the next few hours, as we sat slurping Chinese tea in an outdoor restaurant beside a dusty street, Mr Wong described how he, personally, felt that the official story of the famous Long March was seriously inaccurate.

Communist history is full of lies, he whispered.

This was either very brave or very foolish. Questioning the official line on this historic event was always going to end in tears, for the Long March was portrayed as a key episode in the Civil War between the government forces of Chiang Kai-shek and Maos Communist Party. To dispute its authenticity was tantamount to questioning Mao himself, who had personally overseen and contributed to its written account.

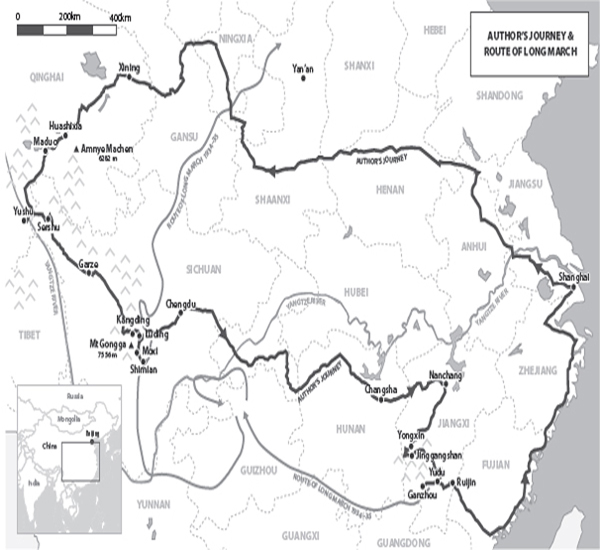

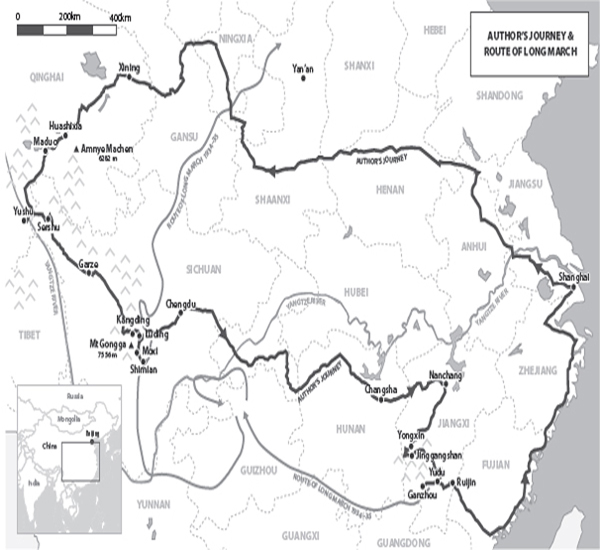

What was true was that, after a great deal of political strife and violent skirmishes against Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist governments regime, the Chinese Communist Party was born in 1931 in Jiangxi province, in southeastern China. In reply, Chiang Kai-shek sent wave upon wave of what he called annihilation forces to wipe it out. For three years, the Communists held the Nationalists at bay, until the fledgling Communist Red Army found itself surrounded, pinned down in the mountains of Jiangxi. However, after the Nationalists launched one final, powerful offensive involving 500,000 troops, Mao and the Communists managed, in October 1934, to break free of this blockade and secretly flee their southern bases. The plan was first to escape, then eventually meet up with other Communists in the northern provinces of Gansu and Shaanxi. This tactical retreat became known as the Long March, even though it was not one march, but several, made up of different armies at first pushing westwards, then to the north. Some 100,000 people set out, but fewer than 10,000 made it to the finish. Those men and women, including high-ranking Communist officials and their wives, endured snow-covered passes, treacherous swamps, raging rivers and, of course, the armies of General Chiang Kai-shek, which pursued them relentlessly. The march lasted 368 days and covered 9,650 kilometres, ending in Shaanxi province. In all, 24 rivers were crossed, 18 mountain ranges were climbed and 11 provinces were traversed before the journey finally finished on the edge of the Gobi Desert in the caves of Yanan, a location that would become the Communists main base for the next 13 years.

In a Party conference speech in 1935, soon after the march had ended, Mao called the Long March a manifesto that had shown the Red Army to be heroes, a propaganda force that pointed the way to liberation, and a seeding-machine that would yield a great harvest across all of China.

Clearly that seed hadnt reached Mr Wong, whose doubts were almost certainly well founded. The Party is now known to have embellished many parts of the story of the Long March in order to depict it as a glorious moment in Chinas nationhood. The Battle of Xiang River in Guangxi, fought in the early part of the march, is one such event with a slightly embroidered history. Though a battle in which the Communists lost tens of thousands of men, it was painted as a victory where those soldiers had sacrificed their lives, paying the ultimate price in order to allow their fellow marchers to escape. In actual fact, it is now thought that at least half of them simply deserted. Many of Maos armed forces had been forcibly recruited and so, facing the vastly superior forces of Chiang Kai-shek, they had shouldered their rifles and made a run for it. Not that you would know that from the official description of this particular battle. Clearly, Mao was never one for letting the facts get in the way of a good story.

Next page