E.H. GOMBRICH

This book was first published to accompany an exhibition in the Sunley Room at the National Gallery, London, June 1995

New edition The Estate of E.H. Gombrich 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

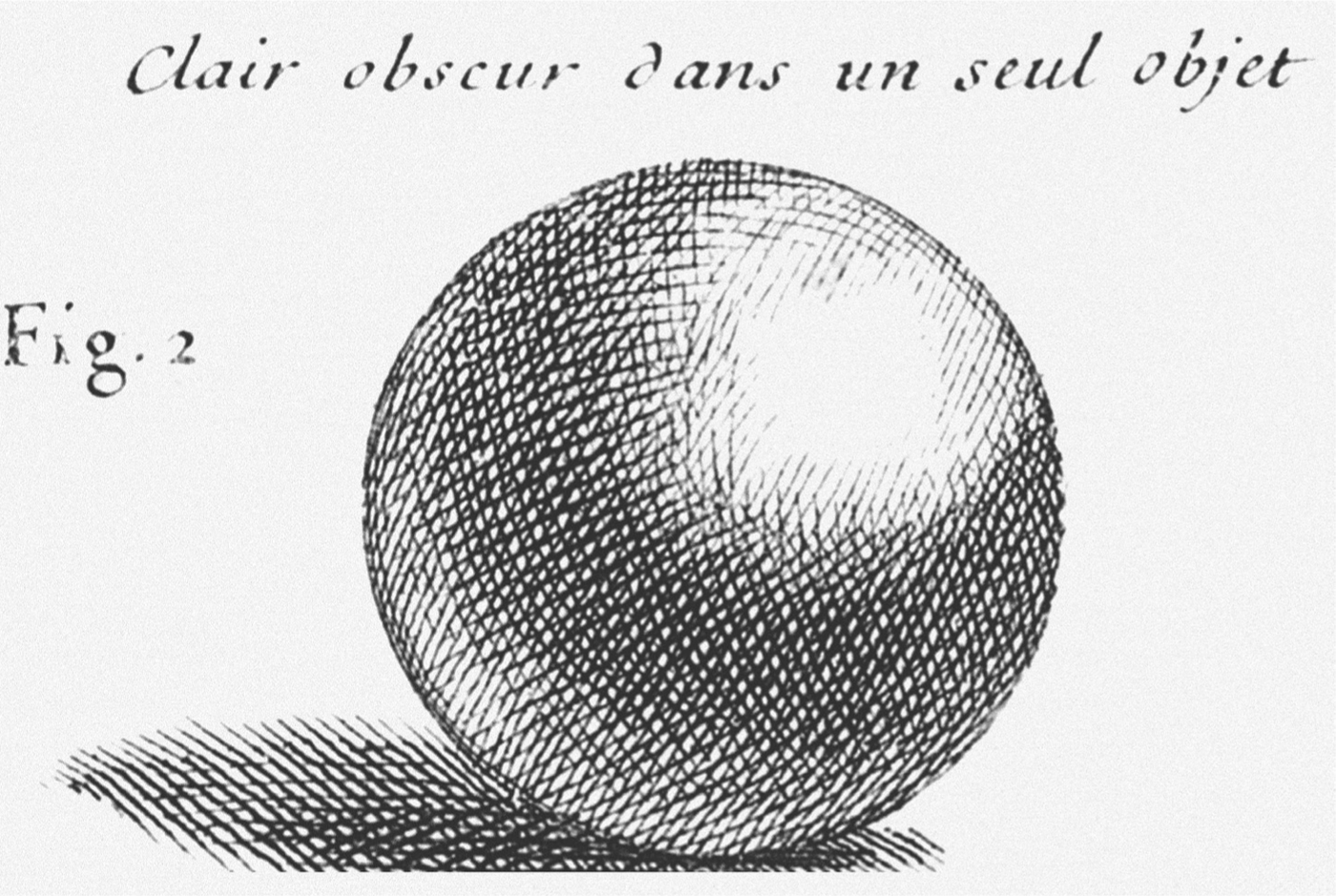

Detail of an engraving from Roger de Piles, Elmens de la Peinture Pratique, Paris 1684.

Shadow: The darkness created by opaque bodies on the opposite side of the illuminated part.

Shadow: In the language of painters it is generally understood to refer to the more or less dark colour which serves in painting to give relief to the representation by gradually becoming lighter. It is divided in three degrees called shadow, half-shadow and cast shadow. By shadow (ombra) is meant that which a body creates on itself, as for instance a sphere that has light on one part and gradually becomes half light and half dark, and that dark part is described as shadow (penumbra). Half-shadow (mezz ombra) is called that area that is between light and the shadow through which the one passes to the other, as we have said, gradually diminishing little by little according to the roundness of the object. Cast shadow (sbattimento) is the shadow that is caused on the ground or elsewhere by the depicted object...

After Filippo Baldinucci, Vocabulario Toscano dellArte del Disegno, Florence 1681.

FOREWORD

Like every art historian of my generation, my way of thinking about pictures has been in large measure shaped by Ernst Gombrich. I was fifteen when I read The Story of Art and like millions since, I felt I had been given a map of a great country, and with it the confidence to explore further without fear of being overwhelmed.

I hope so personal a beginning may be forgiven in the catalogue of a public exhibition, but it is a striking effect of Gombrichs style that his readers feel they are being personally addressed, engaged, if not quite in a dialogue, then in a kind of individual tutorial. These tutorials have ranged widely in subject, but have repeatedly returned to questions of perception, about how we organise information gained from looking, how we turn sight into insight.

It is a sad truth, repeatedly brought home to us by Gombrich, that most of us can see only what we have already learnt is likely to be there. A botanist will spot distinctions between leaves or petals that escape others, but may in turn miss the details that enthral motor-car enthusiasts. To be observant, we need first to be given something to look for. In this exhibition (generously supported by the Bernard Sunley Foundation), we are looking not for a thing, but its shadow, and a shadow of a particular sort. As soon as the problem is set, we find we can in fact now see and ponder for ourselves what before we had missed: why are shadows only sometimes present, and what is the artist using them to achieve?

It is the mark of the great teachers that they leave us feeling that we have found things out for ourselves. Many of us have, I am sure, put down a Gombrich essay believing that we had been on the verge of that very insight, that we had been standing just behind him, looking over his shoulder on the Darien peak. But we were not. And without him much delight would have remained undiscovered and unconsidered.

This small exhibition is the National Gallerys way of saying thank you to Sir Ernst Gombrich, OM, who has enriched for so many the pleasure to be found in looking at pictures.

Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum

INTRODUCTION

When the National Gallery wished to honour Sir Ernst Gombrich with a small exhibition in 1995, he responded with characteristic generosity. The topic selected was well suited to someone who was interested in both science and art and had done so much to explore the conventions for representing substance and light. Today we might prefer to present such diverse material as a special feature on a website, but this small book, reprinted here some twenty years later, still serves, like the original modest exhibition, as a valuable introduction to a large subject.

We are aware of shadows early in the morning, when the sun is low in the sky, dew is still on the ground and a slight mist hovers over the water. At that time of day those who herd cattle or shoot duck, as in the great landscape painting by Cuyp (), find the paths barred by the shadows of the trees. In the late afternoon, when the shadows lengthen, we become aware of them again. And when the moon is full and the sky clear, the outside world fills with strange shapes shapes with no substance.

Plate 1 Aelbert Cuyp, River Landscape with Horseman and Peasants, about 165860. Oil on canvas, 123 241 cm.

).

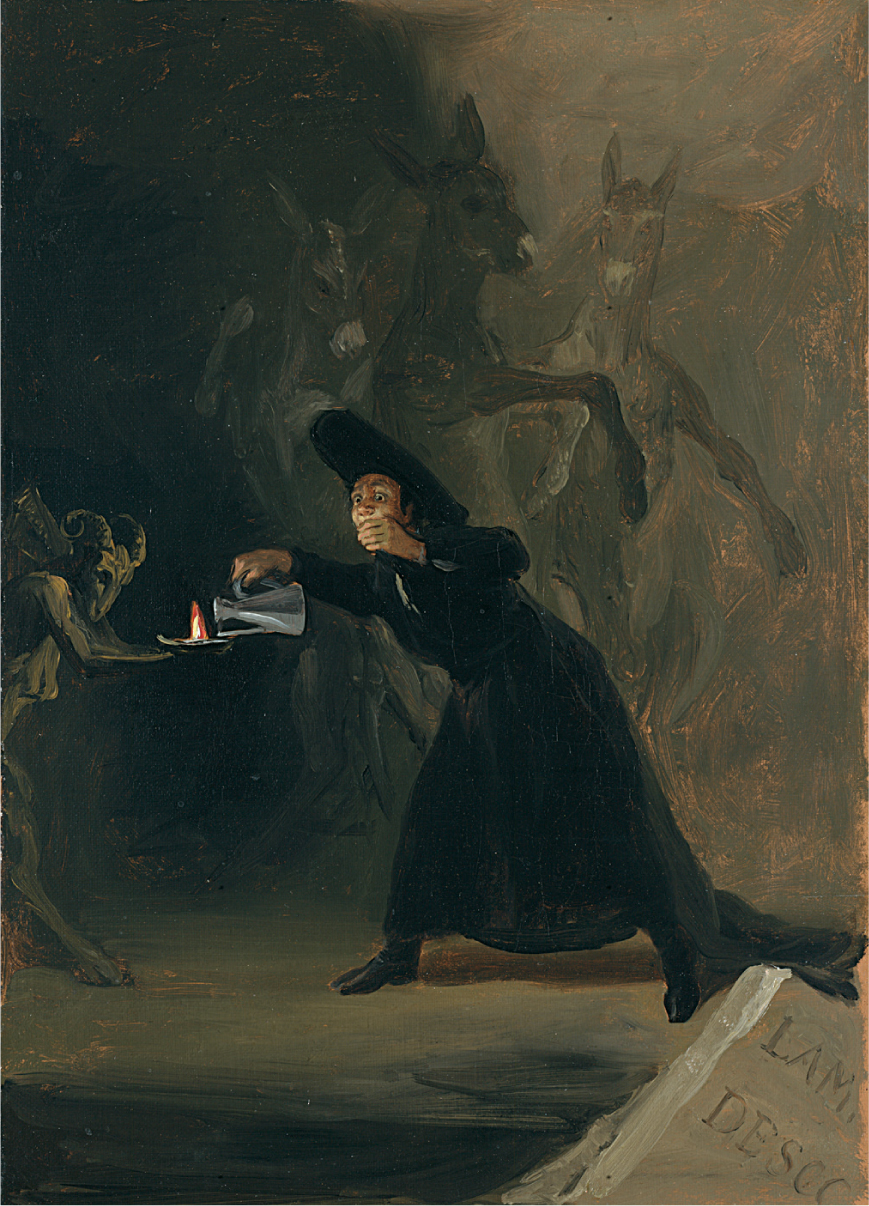

The shadows we meet with indoors at night are only less intimidating because they are more familiar. Indeed, we are most likely to notice shadows when we are sitting in relative darkness, dependent for light upon a candle or an oil lamp or merely a fire, as was once not only a common experience but an everyday one. The complete illumination of a room at night must have been exceedingly rare before the use of gas or electric light.

Plate 2 Francisco de Goya, A Scene from El Hechizado por Fuerza (The Forcibly Bewitched), 1798. Oil on canvas, 42.5 30.8 cm.

Plates 3 and 4 William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode: 5, The Bagnio, about 1743. Oil on canvas, 70.5 90.8 cm.

Hogarths Marriage A-la-Mode traces the consequences of a marriage of convenience between an aristocratic rake and the daughter of a wealthy city merchant. The series of six paintings moves from social satire to grim tragedy. The fifth one () one outside the painting itself, in our space.