Retracing the Bards Unknown Travels

Richard Paul Roe

THE SHAKESPEARE GUIDE TO ITALY. Copyright 2011 by Richard Paul Roe.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Photoshop work on authors photographs by Stephanie Hopkins.

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-06-207426-3 (pbk.)

EPub Edition OCTOBER 2011 ISBN: 9780062074270

11 12 13 14 15 SCP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 Romeo and Juliet

Devoted Love in Verona

CHAPTER 2 The Two Gentlemen of VeronaPart 1

Sailing to Milan

CHAPTER 3 The Two Gentlemen of VeronaPart 2

Milan: Arrivals and Departures

CHAPTER 4 The Taming of the Shrew

Pisa to Padua

CHAPTER 5 The Merchant of VenicePart 1

Venice: the City and the Empire

CHAPTER 6 The Merchant of VenicePart 2

Venice: Trouble and Trial

CHAPTER 7 Othello

Strangers and Streets, Swords and Shoes

CHAPTER 8 A Midsummer Nights Dream

Midsummer in Sabbioneta

CHAPTER 9 Alls Well That Ends Well

France and Florence

CHAPTER 10 Much Ado About Nothing

Misfortune in Messina

CHAPTER 11 The Winters Tale

A Cruel Notion Resolved

CHAPTER 12 The Tempest

Island of Wind and Fire

I had not admitted to anyone why I was going to Italy this time. My friends knew that I went there whenever I could, a reputation that gave me the cover that I wanted for my fools errand in Verona. But was it so foolish? Had I deluded myself in what I had come to suspect? Only by going back to Verona would I ever know. Of that much I was certain.

Then I arrived, and stepping outside my hotel, glad I had come, conflicting emotions began to make my blood race. I was half excited with the beginning quest, and half dreading a ridiculous failure, but obsessed with the idea of discovering what no one had discoveredhad even looked forin four hundred years.

My start would bewas planned to beabsurdly simple. I would search for sycamore trees. Not anywhere in Verona but in one place alone, just outside the western wall. Native sycamore trees, remnants of a grove that had flourished in that one place for centuries.

In the first act, the very first scene, of Romeo and Juliet the trees are described; and no one has ever thought that the English genius who wrote the play could have been telling the truth: that there were such trees, growing exactly where he said in Verona. In that first scene, Romeos mother, Lady Montague, encounters her nephew on the street. His name is Benvolio; he is Romeos best friend. She asks Benvolio where her son might be. Listen to Benvolios answer:

Madam, an hour before the worshippd sun

Peerd forth the golden window of the East,

A troubled mind drave me to walk abroad,

Where, underneath the grove of sycamore

That westward rooteth from the citys side,

So early walking did I see your son. (Emphasis mine)

The author who wrote those lines did not invent the story of this immortal play. Many think that he did, but he didnt. He borrowed it. It was an old Italian tale. The man who recorded it for its first printing in 1535 reported that this was so. He was Luigi da Porto, and he said that he had heard the story told many times. Da Porto did not mention any sycamore trees. But after all, he was not a native of Verona; he was a nobleman of Vicenza.

When da Portos story was published in 1535, it was soon borrowed and embellished by another Italian, a great storyteller named Matteo Bandello. Bandello did not give us any sycamore trees either. Then a French writer, Pierre Boaistuau, took over Bandellos rendition and put it into French, adding whimsies of his own and some goofy descriptions about Italy; but he did not include any sycamore trees.

Boaistuaus narrative soon arrived in England, where it underwent more transformations. One Englishman, named William Painter (or Paynter), wrote a modest prose version; but another, a lad named Arthur Brooke, got carried away. Brooke wrote the story as a tedious poem that he filled with fantasies, asides, and moralizations. It took him 3,020 lines to finish the job. Brooke claimed that he used Bandello, but he didnt; he really used Boiastuau. You can tell, because his poem has Boiastuaus embellishments. Brooke had plenty of room for some sycamore trees, but there arent any. No one pays much attention to Painter, but just for the record, there are no sycamores in Painters prose either.

All of this evolution happened before the Romeo and Juliet of the playwright was composed. Shakespeare scholars insist that he got his material for Romeo and Juliet from Brookes enormous poem and that the celebrated playwright had never been in Italy; therefore, he could be expected to make mistakes about its topographic realities. They say he invented a peculiar Italy of his own, with colorful nonsense about what was there. But (and here is the inexplicable thing) alone in the playwrights Romeo and Julietthere and nowhere else, not in any other Italian or French or English versionhas it been set down that at Verona, just outside its western walls, was a grove of sycamore trees.

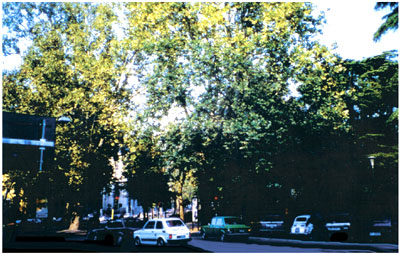

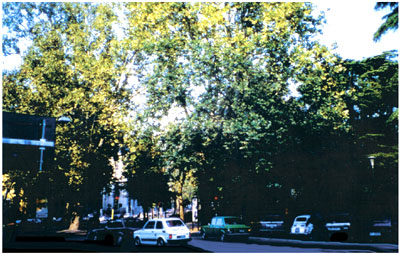

My driver took me across the city, then to its edge on the Viale Cristoforo Colombo. Turning south onto the Viale Colonnello Galliano, he began to slow. This was the boulevard where, long before and rushing to the airport at Milan, I had glimpsed trees but had no idea what kind.

Creeping along the Viale then coming to a halt, the driver, with a proud sweep of his hand exclaimed: Ecco, Signore! There they are! It is truly here, outside the western wall that our sycamores grow. And there they were indeed. Holding my breath for fear they might be mere green tricks of the sunlight, I leapt from the car to get a closer look at the broad-lobed leaves and mottled pastel trunks, to make absolutely certain that it was true; that the playwright had known, and had told the truth. Benvolio was right. And I was not a fool.

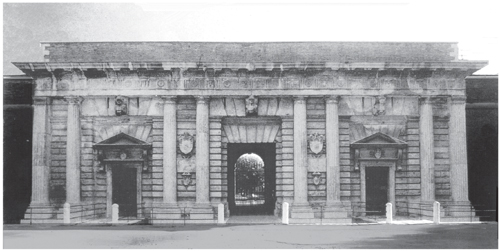

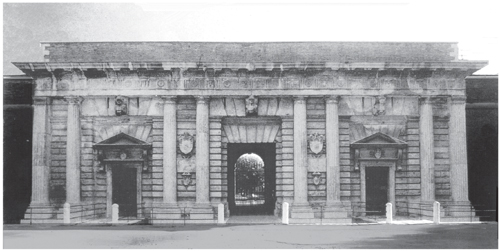

The Porta Palio, one of Veronas three western gates. Sycamore trees can be seen through the archway. (Authors photo)

Sycamore trees outside the Porta Palio. (Authors photo)

Now the trees are in separated stands, the ancient grove cut and hacked away by boulevards and crossings, by building blocks and all the ruthless quirks of urbanization. But the descendants of Romeos woodland are still growing where they grew in Romeos day. Rejoined in the minds eye, erasing the modern incursions, those stands form again the grove that once, four and far more centuries ago, was the great green refuge of a young man sick with love.

Next page