Contents

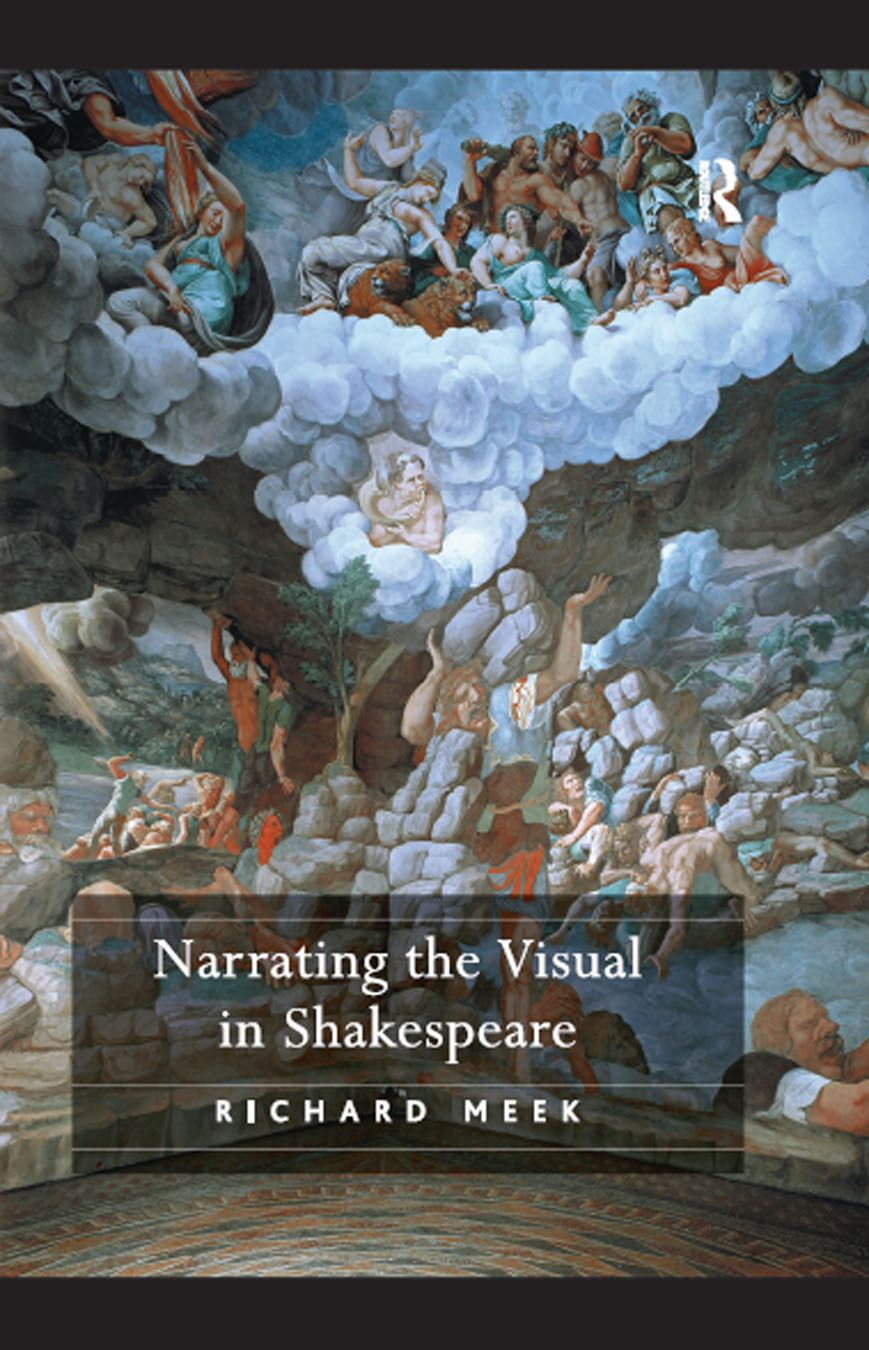

NARRATING THE VISUAL IN SHAKESPEARE

Narrating the Visual in Shakespeare

RICHARD MEEK

De Montfort University, UK

First published 2009 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Richard Meek 2009

Richard Meek has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Meek, Richard

Narrating the visual in Shakespeare

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616 Technique 2. Narration (Rhetoric) 3. Mimesis in literature 4. Visualization in literature 5. Visual perception in literature 6. Imagery (Psychology) in literature

I. Title

822.33

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meek, Richard, 1975

Narrating the visual in Shakespeare / by Richard Meek.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7546-5775-0 (alk. paper)

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Technique. 2. Narration (Rhetoric) 3. Mimesis in literature. 4. Visualization in literature. 5. Visual perception in literature. 6. Imagery (Psychology) in literature. I. Title.

PR2997.N37M44 2009

822.33dc22

2008042608

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-5775-0 (hbk)

Contents

.

.

.

.

.

.

There are various colleagues, friends and institutions I would like to thank for their help and support in the writing of this book. The book grows out of doctoral research that was carried out at the University of Bristol, and I am grateful to John Lyon, George Donaldson, John McWilliams, Sarah Gallagher and John Lee for their advice, conversation and friendship during this time. I am also grateful to Michael Hattaway for his comments and subsequent support. I am particularly indebted to Neil Rhodes, who organised an excellent seminar on Shakespeare and Oral Culture at the 2005 British Shakespeare Association Conference at Newcastle University, where I presented a paper that became the books coda. His subsequent comments on the project and professional support have been invaluable. Other parts of the book were presented at conferences at the Universities of Oxford, Lancaster and St Andrews, and I would like to thank everyone who offered feedback on those occasions.

Several scholars read parts of my work in progress. Ann Thompson generously read the Hamlet chapter and made many shrewd and helpful suggestions. Her encouragement was much appreciated. Bill Sherman read the Introduction and made some particularly astute observations and suggestions for refinement. Thanks to John Roe, who also read the Introduction along with the first two chapters. I would particularly like to thank Michael Greaney, who read a large part of the manuscript and offered a great deal of judicious and intelligent advice; I am especially grateful for his expertise in the field of literary theory. Financial support of various kinds was provided by the University of Reading, Kings College London and the F.R. Leavis fund at the University of York. The School of English and American Literature at Reading provided funds for a rewarding trip to the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the Department of English at Kings enabled me to spend a very pleasant and productive month at the Huntington Library as the project neared completion. I would like to thank all the staff at Ashgate, in particular Erika Gaffney for her efficiency, enthusiasm and patience throughout. I am also grateful to the anonymous readers at the press for their comments. I would also like to thank John Banks for his excellent copy-editing.

Some of the material in the book has appeared previously. Parts of appeared in Richard Meek, Jane Rickard and Richard Wilson (eds), Shakespeares Book: Essays in Reading, Writing and Reception (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008). An earlier version of the Coda appeared as The Promise of Satisfaction: Shakespeares Oral Endings in English, 56/216 (Autumn 2007). I am grateful for the permissions to reprint this material; I would also like to thank the academic readers at SEL and English for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Finally, I would like to thank my partner Jane Rickard. It is difficult enough to express my gratitude for Janes endlessly insightful and often inspirational comments on the various drafts of the book as it took shape. But I also have to find the words to thank Jane for her warm encouragement and wonderful companionship over the last four years, without which I suspect that the book might never have appeared at all. I cannot sum up sum of half my wealth. Thank you for everything.

In the Induction to The Taming of the Shrew, one of Shakespeares earliest plays, a Lord and his servants perpetrate an elaborate confidence trick upon the hapless tinker Christopher Sly, in an attempt to make him believe that he, too, is a Lord. Part of this process of persuasion and seduction involves the description of several works of pictorial art:

2 Serv. Dost thou love pictures? We will fetch thee straight

Adonis painted by a running brook,

And Cytherea all in sedges hid,

Which seem to move and wanton with her breath,

Even as the waving sedges play with wind.

Lord. Well show thee Io as she was a maid,

And how she was beguiled and surprisd,

As lively painted as the deed was done.

3 Serv. Or Daphne roaming through a thorny wood,

Scratching her legs that one shall swear she bleeds,

And at that sight shall sad Apollo weep,

So workmanly the blood and tears are drawn.

According to the Lord and his servingmen, these pictures are so realistic that one would be forgiven for mistaking them for the thing itself. The sedges or grasses in which Venus (Cytherea) hides seem to move (52), while the painting of Io is said to be As lively painted as the deed was done (56). Furthermore, the dense syntax of the passage means that it is unclear whether Apollo is a character depicted within the painting, weeping at the sight of Daphne herself, or an observer of this extraordinary picture, moved by the workmanly (60) representation of her blood and tears. These descriptions seem designed, then, to blur the distinction between representation and reality, and between viewer and participant. It is worth emphasising, however, that these artworks are all kept offstage. The Lord and his men tantalise Sly with the promise of visual satisfaction, saying that they will fetch [him] straight (49) the picture of Venus and Adonis, and will show [him] Io (54), but this does not take place within the action of the play. Perhaps the Lord and his co-conspirators realise that it might be better if Sly doesnt see these absent artworks and instead imagines this extraordinary mode of verisimilitude. But of course Shakespeares audience does not get to see these artworks either. Does Shakespeare implicitly suggest that such pictures are best left to the imagination? If so, is the deception that the Lord practises upon Sly markedly different from the ways in which Shakespeares plays beguile us with vivid descriptions of things unseen?