Acknowledgments

I am thankful to my audiences, who have read or listened to portions of this study at meetings of the Modern Language Association, the New College Conference on Medieval-Renaissance Studies, the International Congress on Medieval Studies, and the Shakespeare Association of America. An earlier version of Chapter 5 appears in Othello: New Perspectives (Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Presses, 1990), and Chapter 6 originally appeared in Shakespeare Survey, 38 (1985). I am grateful to the editors of Associated University Presses and Cambridge University Press for permission to reprint this material.

I would also like to thank those who have helped in the making of this book by reading the manuscript at various stages: Miriam Miller, Ira Clark, Jack Perlette, Raeburn Miller, Richard Katrovas, Jessica Munns, Marie Nelson, Sally Cole Mooney, Susan Krantz, and Michael Shapiro. Virginia and Herbert Schwab, Robert Bourdette, George Faltings, and Edward, Mary, Maryrose, James, and Eddie Mooney helped along the way. Joanne Ferguson, Editor-in-Chief at Duke University Press, has been exceptionally kind and professional. R. Mark Benbow grounded me in Shakespeare's text, and Edward Partridge became a critic and friend at an important time. Jackson I. Cope told me to read Weimann and has stood by me since we first considered the "jigging veins of rhyming mother wits."

-ix-

[This page intentionally left blank.] |

|

these hemispheres. The theatrical experience needs to be better understood as an aesthetic transaction in which information, in the forms of language, gesture, and action, moves across the invisible line separating actors and audiences. Indeed, I share the belief that "as long as the performance of the play is substantially enriched by the potential ... significance involved in the actor-audience relationship, the full meaning of drama may be defined as an image of the impact of this relationship on the performed text. And the more the public is drawn into the world of the play and the more that the play is drawn into the real world, the more the essence of the play is brought out in the course of performance. The relationship between actor and audience is, therefore, not only a constituent element of dramaturgy, but of dramatic meaning as well."

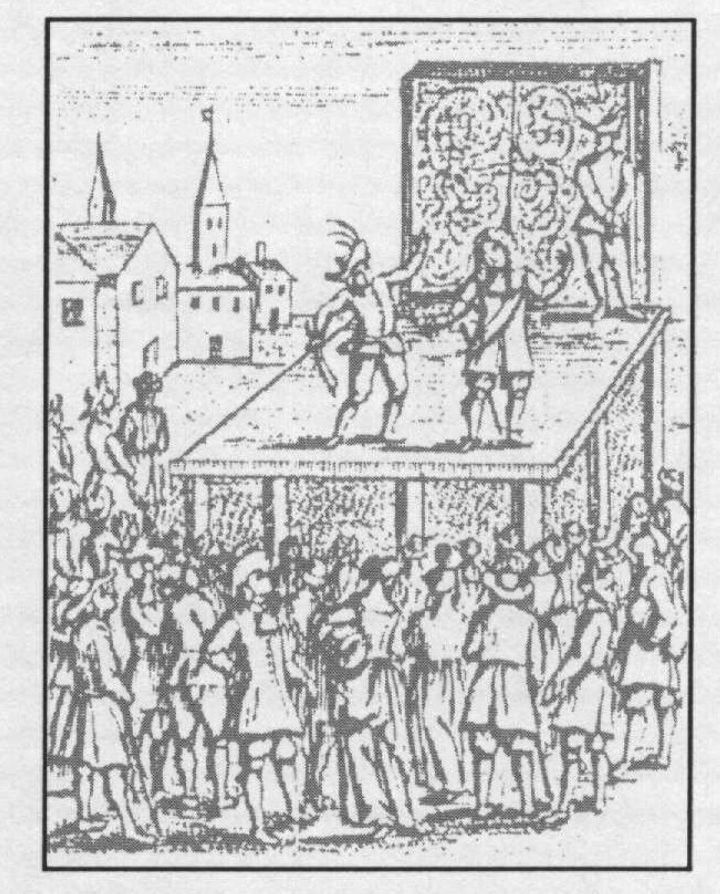

These are the words of Robert Weimann, whose work I have drawn upon for my methodological approach. When his Shakespeare und die Tradition des Volkstheaters first appeared in 1967, it was hailed as a "milestone in Shakespeare criticism" and the finest work to come out of Germany since Wolfgang Clemen's Shakespeare's Bilder in 1936. Until it was translated and republished as Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the Theater in 1978, however, Weimann's book did not reach a wide audience; even now scant attention has been paid to this signal contribution to Shakespeare scholarship. This study stresses the importance of Weimann's work. In the chapters that follow I apply his complex idea of Figurenposition (or "figural positioning") and his thesis about the "traditional interplay" between a downstage place (or platea) and an upstage location (or locus) to Shakespearean tragedy. I outline my approach by reexamining the "affective" and "intentional" fallacies and by presenting a number of pre-Shakespearean dramatic paradigms that challenge accepted notions about the nature of Renaissance dramatic illusion. I then assert the relevance of Weimann's study to the relation between an actor and his role(s) and to the correlation between a play's language and staging. In the analyses of Richard III, Richard II, Hamlet, Otbello, King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra that follow, I apply these ideas in an attempt to envision the plays in performance. Each analysis may be read independently, but it has been my intention to proceed cumulatively, focusing, in each chapter, on a different dimension of the actor-audience relationship. Taken together, these essays explore the nature of Shakes

-xii-

peare's dramaturgy and examine the ways in which he presents his major characters.

These chapters consider the verbal structures and theatrical functions implied by as well as interpretatively present in the texts. They posit a group of spectators for whom the plays were performed, a performance subtext, and an interpretative line for major characters. As such, they raise a number of theoretical issues, and it is important to acknowledge them at the outset. There are very real difficulties inherent, for instance, in positing "an" audience for a Shakespearean play and even more in suggesting how it might have responded. Shakespeare's audiences and critics have responded in so many different ways in the last four hundred years that response cannot be the product of a definitive intentionality and a unitary reception. I therefore include a range of possible reactions in my discussions of the nature of Shakespeare's transactions with "the" audience. I need to stress, however, that I am most concerned with theater as a communal event and with a play's overall effect. I do not think it very helpful to argue that response is necessarily ambivalent, indeterminable, or multivalent or that all responses are equally valid. Audiences do not generally experience contradictory interpretations when a play is performed with a consistent subtext in mind. Indeed, one of my intentions is to persuade readers that we can begin to write about authorial intention and communal effect.

The performance subtexts and interpretative lines I posit are derived, empirically, from the nature of the stage conventions and the differences in the characters' Figurenpositionen. Although they often support accepted critical opinions about, for example, the function of animal and mercantile imagery in Othello sometimes they do not. I recognize that literary study, even an historically based textual criticism, is interpretative. When I juxtapose literary with playable values and reconsider accepted critical views in terms of