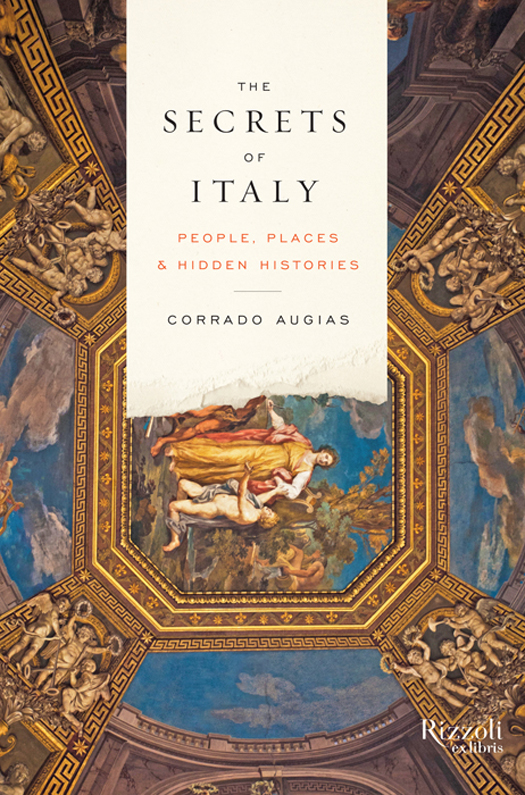

ALSO BY CORRADO AUGIAS, AVAILABLE IN ENGLISH

The Secrets of Rome:

Love and Death in the Eternal City

First published in hardcover in the United States of America in 2014

by Rizzoli Ex Libris, an imprint of

Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

300 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10010

www.rizzoliusa.com

Originally published in Italy as I Segreti dItalia

Copyright 2012 RCS Libri S.p.A., Milano

Translation Copyright 2014 Alta L. Price

This ebook edition 2014 RCS Libri S.p.A., Milano

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8478-4275-9

v3.1

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The most recent in a long line of books centering on the specificity of place and the way history, culture, and literature intertwine, Corrado Augiass The Secrets of Italy is best read as a meandering stroll through time, in the company of some curious characters. Like his previous books on Rome, London, Paris, and New York, this is a series of essays highlighting unique episodes in Italian history. Because the scope has been broadened from one specific city to an entire country, introductory chapters on Italy as a whole lead into the discussions of individual places and people.

The author is a distinguished journalist, essayist, former parliamentary representative, and television host who aims to make history accessible and bring literature to life for the average twenty-first-century citizen. He has provided notes and sources for many of his references, and in addition to providing English publication information where available, I have added notes where more details would be helpful. Naturally, the original presumed a fair amount of knowledge most non-Italians would be unfamiliar with, so I strove to provide the necessary background without intruding on the authors work. Notes aside, it is our hope that the main text stand on its own, as a personal musing enriched by excerpts from the work of other writers.

A final word on terminology and perspective: because Italy is a relatively young country, many of the events discussed here did not technically take place in Italyrather, they happened in the many territories that predated unification. Italy as we currently know it was only unified in 1861, and to this day many of its residents feel it remains a rather divided country in terms of political, linguistic, and cultural differences. Therefore, I have maintained the authors references to the Italian peninsula in pre-1861 passages so as to respect that historic distinction. The many chapters of this book skip around from North to South and East to West, drawing connections and highlighting the unique aspects of each area. Italy exists in the heart and mind as much as it does on the geographic map, and I hope this translation offers the reader new insight into its most intriguing corners.

ALP

A PREFACE, OF SORTS

Id like to begin with an episode that perhaps still holds some significance. Its a distant memory but is seared into my mind with the clarity often granted to recollections of childhood events, especially those that took place at epic moments. The Villa Celimontana in Rome is a gorgeous place where not many people go. Unfairly, it is less famous than the Villa Borghese or the Janiculum, which is a shame because its lanes dotted with ancient Roman ruins, its woods, the hidden little obelisk, the palazzo that houses Italys Geographic Society, and the hill overlooking the gigantic remains of the Baths of Caracalla all help make it one of the enchanted places that the city offers those who know how to find them. Its one of the many spots in Rome where neoclassic and romantic canons intertwine, becoming indistinguishable from one another.

As its name implies, the villa is located atop the Caelian, a hill once covered by vineyards that the prominent Mattei family transformed into a peaceful rural garden oasis in the sixteenth century. The main entrance is next to the basilica of Santa Maria in Domnica (also known as Santa Maria alla Navicella), one of the ancient early Christian basilicas that are so much more beautiful than the more lavish baroque ones that ended up becoming the citys stylistic hallmarks. I highly recommend it.

In June 1944 American troops had set up camp in the villa. It was solidly fenced off, looming atop a wall overlooking the Via della Navicella, so it was a natural choice for stationing troop quarters. Up sprouted tents, shacks, the ever-present flagpole waving the Stars and Stripes, bugle callseverything that comes with a military encampment. That flag was also the first flag I ever saw at half-mast, and my mother explained why: Their president has passed away, she said. So it must have been April 1945, since the 12th of that month marked the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the man who had held the country together through endless war.

But the memory I wanted to share is a different, earlier one. It was a Sunday and the air was neither cool nor hot, so it was probably sometime around the fall of 1944 when, with the occupation over, the city began trying to come back to life. My mother held my hand as we walked home past the Villa Celimontana after visiting a friend. A festive group of American soldiers leaned out over the top of the wall, dressed in neat uniforms with crisp folds in their freshly ironed shirts. I was used to seeing Italian infantrymen with loosened or sagging greaves, in uniforms of uselessly heavy, coarse cloth. The Americans freshly ironed shirts, robust khaki belts, and the scent of soap, tobacco, and brilliantine all struck me as the absolute paragon of eleganceindeed, of true wealth. It looked like they were having a great time up there. One by one they drew cigarettes from their packs and tossed them down to the streetone cigarette, another cigarette, then anothertaking their sweet time between one toss and the next. A crowd of young Italian men stood at the foot of the wall; at each toss they dashed forward, pushing toward the spot the cigarette would land. It was part play, part brawl, part competition, and all tumult. My mother crossed the street, pulling me away; perhaps I turned to watch, and the scene quietly lay in some corner of my mind all these years.

Many years later, on yet another Sunday, I took my daughter to the zoo. In front of one of the cages a group of people, also festive, were tossing nuts to the monkeys inside. Their gestures echoed those of the soldiers and the distant memory surfaced. Not that I was at all comparing the poor young Romans of 44 to monkeysrather, the memory emerged because the roles each played were based on similar behaviors: a mixture of complicity and sheer enjoyment, competition and play, on one side as much as on the other.

Then, after yet more years had passed, as I was working on a history of Rome I happened across a few magnificent lines from the sixth book of the Aeneid. Aeneas has encountered his fathers shadow and tries in vain to embrace him. Anchises then explains his theory of the cycles that govern the universe, prophesies great descendants, and adds that other populations will rise to glory in the arts and sciences. The Romans, on the other hand, will rule the world thanks to the wisdom of law: