Contents

Copyright 2006 by Lawrence Malkin

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

First eBook Edition: March 2008

ISBN: 978-0-31602-916-2

ATTACK THE POUND THE WORLD AROUND

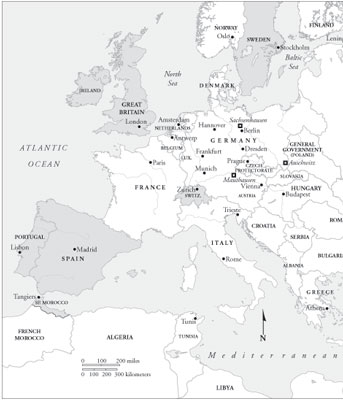

T he Second World War was barely two weeks old when leaders of Nazi espionage and finance gathered in a paneled conference room in Germanys Finanzministerium, at Wilhelmstrasse 61. Like that of the other overbearing buildings lodged behind pseudoclassical fronts, its architecture was proud and brooding. Most windows gracing this official avenue were topped by a heavy triangular tympanum. But the Finance Ministry had been erected in the 1870s without this classical adornment, adopting instead the Italianate style of a Medici palace. Wilhelmstrasse, Berlins Pennsylvania Avenue, its Whitehall, gloried in the name of the kaisers of imperial Germany. The Finance Ministry stood toward its southern end. Farther down, the street was intersected by Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse, where stood a huge, pillared palace, the L-shaped headquarters of the Gestapo.

The plan on the Ministrys conference table on September 18, 1939, was simple. Why not have the Reichsbank print millions of counterfeit British banknotes, unload them on the streets and rooftops of the enemy, and then stand aside as the British economy collapsed? The dubious idea of printing enemy currency was not especially new or even original; similar plans also rippled across the desks of no less than Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. A hundred and fifty years before, the British had counterfeited the currency of the French Revolution to stoke the inflation already created by the revolutionaries own printing presses. And Frederick the Great, who perfected the unforgiving Prussian military ethos that molded the German state, had also forged money to undermine his eighteenth-century enemies. But these schemes had all been hatched in a preindustrial age. Now, given the immense resources and brutal efficiency of Adolf Hitlers war machine, it should be much easier to print English banknotes on a vast scale, in greater quantities than any counterfeit bills ever produced before.

It was not beyond calculation that the Nazi plot could devastate the economy of Britain and its empire, whose worldwide commerce was transacted through the financial nerve center of the City of London, which enriched Britains gentry while financing its wars. Details were put forward by Arthur Nebe, chief of the SS criminal police. Nebe, a schoolteachers son and an ambitious, opportunistic senior civil servant, habitually injected himself into the many conspiracies that lay at the heart of the Nazi movement. He was a party member even before Hitler came to power in 1933, whose principal utility was his knowledge of the criminal underworld. Inventive and sinister, he was ever at the service of his superiors. Nebe had helped Hitler win supreme command of the armed forces in 1938 by fingering War Minister Werner von Blombergs new wife as a former prostitute, forcing the old Prussians resignation in disgrace. Nebe was the German representative on the International Criminal Police Commission, formed after World War I principally to track counterfeiters and drug smugglers across Europes borders and later known as Interpol, from its cable address. After the Nazis marched into Austria in 1938, they moved the commissions headquarters from Vienna to Berlin, gaining access to fifteen years of case files and suborning its original purpose of tracking counterfeiters and drug smugglers. (Nebe also helped adapt the mobile gas van, originally used in the Nazi euthanasia of mental patients, for mass murder in Eastern Europe to soothe the sensibilities of the Reich security chief, Heinrich Himmler, who said he could not stand the sight of people being shot, even Jews.)

Nebe proposed mobilizing the extensive roster of professional counterfeiters in his police files. His immediate superior was Reinhard Heydrich, protg of Himmler, the leader of the murderous SS, the Schutzstaffel (Defense Squadron), that began as the Nazi Partys armed militia. Heydrich was not in the least constrained by any legal scruples or even police protocol in rejecting Nebes proposal, but he excluded the use of police files lest this discredit Germanys control over the international police organization, of which he was titular chief. Instead, he wanted to continue using the commissions European network to track down anti-Nazis and Jews who had escaped from Germany. Heydrich also hoped to extend his reach as far as the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation in order to obtain U.S. passport forms for possible forgery. (The FBI remained hesitantly in touch with the International Criminal Police Commission, breaking all contact only three days before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.)

However resistant he was about using criminal files, Heydrich was enthusiastic about the counterfeit plan from the start. As cunning as he was cruel, he was an avid reader of spy stories. He liked to sign his memos with the single initial C in the mode of the English espionage thrillers fashionable between the wars. (It was and in fact remains the code letter for the chief of the British secret service.) Heydrichs days were full of dark assemblings. He ran Himmlers Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), the Reich Central Security Office. It compiled huge files on Germans suspected of disloyalty or liberal connections, and of course on Jews, whose methodical extermination Heydrich planned and initially supervised. He had his office in the Gestapo building itself, and his SS intelligence network eventually rivaled and finally took over the Abwehr, the old-line military espionage service headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, who had been first officer on the training ship on which Heydrich had sailed as a naval cadet.

Heydrich was as physically self-confident as Himmler was shy and short-sighted. He was a skier, aviator, and fencer, and succeeded at whatever he did, even at playing the violin with fierce emotion, as he had with Frau Canaris as a young officer at the Canarises musical evenings. Heydrichs inner tensions were betrayed principally by his high, metallic voice, his harsh temper, and his nightclubbing habits in Berlin, where the women preferred his aides to the wolf-eyed officer with prodigious sexual appetites.

The only serious objection to the counterfeiting plan came from Walther Funk, a homosexual former financial journalist, fat and well fed, who served as Hitlers economics minister. Funk was the Nazis principal liaison to German industry until the bitter end and the titular head of the Reichsbank. He refused the use of the Berlin laboratories of the central banks print shop, warning that the counterfeiting plan was contrary to international law and that it simply would not work. He was supported by legal advice from the military high command. Funk also demanded that fake bills be barred from Germanys conquered territories. He knew that the locals would dump Nazi scrip for what they thought were real pound notes. The last thing he needed while bleeding their resources for the Reich would be an infusion of forged pounds soaking up his overvalued and suspect occupation currency.