ALSO BY DOMINIC SANDBROOK

Eugene McCarthy: The Rise and Fall of Postwar American Liberalism

Never Had It So Good: A History of Britain from Suez to the Beatles

White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties

State of Emergency: The Way We Were: Britain, 19701974

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2011 by Dominic Sandbrook

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sandbrook, Dominic.

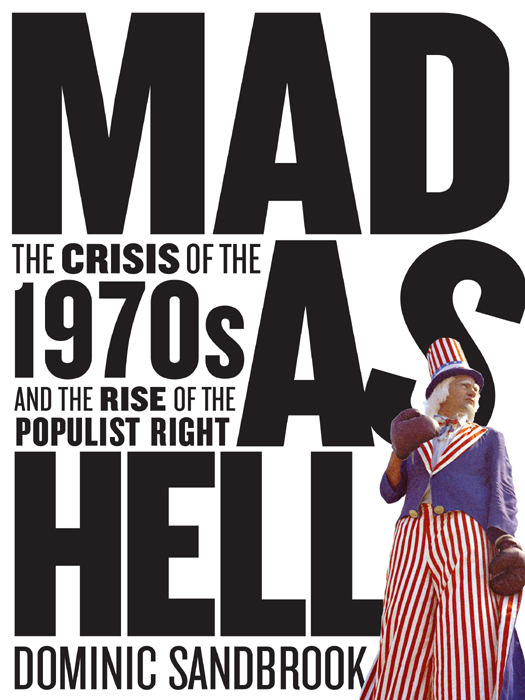

Mad as hell : the crisis of the 1970s and the rise of the populist Right / by Dominic Sandbrook

p. cm.

This is a Borzoi bookT.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59545-4

1. United StatesPolitics and government19741977.

2. United StatesPolitics and government19771981.

3. PopulismUnited StatesHistory20th century.

4. ConservatismUnited StatesHistory20th century.

5. PoliticiansUnited StatesHistory20th century.

6. Political cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century.

7. Social changeUnited StatesHistory20th century.

8. United StatesSocial conditions19601980. I. Title.

E 865. S 26.2010

973.92dc22 2010037726

Jacket art: Associated Press

Jacket design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

For Catherine,

gr mo chro

Contents

Preface

I have to make my witness.

HOWARD BEALE , in Network (1976)

I t is evening in New York City. Lightning flashes overhead, and rain thunders down onto the shabby streets. Far above the crowds, in the tense quiet of a network news studio, a man is staring into a camera. Beneath his shabby beige raincoat, you can just make out the collar of his pajamas. His eyes are blazing, his face is haggard, his gray hair is plastered to his brow. I dont have to tell you things are bad, he says. Everybody knows things are bad. Its a depression. Everybodys out of work or scared of losing their job. The dollar buys a nickels worth, banks are going bust, shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter. Punks are running wild in the street and theres nobody anywhere who seems to know what to do, and theres no end to it.

In the control room, the producers are looking nervously at one another; in the studio, the man is still talking. The air is unfit to breathe, he says; the food is unfit to eat; on television, they tell you that fifteen people were murdered today, as if thats the way its supposed to be. So, he says, you dont go out anymore. You stay at home with your toaster and your TV, and you ask only to be left alone. Well, Im not going to leave you alone, he says, raising his voice, his eyes searing now. I want you to get mad.

I dont want you to protest. I dont want you to riot. I dont want you to write to your congressman, because I wouldnt know what to tell you to write. I dont know what to do about the depression and the inflation and the Russians and the crime in the street. All I know is that first youve got to get mad. Youve got to say, Im a human being, goddamnit! My life has value! So I want you to get up now. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs. I want you to get up right now and go to the window, open it, and stick your head out, and yell: Im as mad as hell, and Im not going to take this anymore!

He is mad, of course: not in the sense of being angry, but in the sense of being demented, deranged, mentally disintegrated. But people are listening. In the studio, word comes that people are yelling in Atlanta, then that theyre yelling in Baton Rouge. In his New York apartment, the president of the news division, an old friend, is watching the anchormans tirade in speechless horror. But his daughter goes to the window and sticks her head out into the darkness and the pouring rain. And she hears first one voice, then another, raised in a swelling public chorus: Im mad as hell, and Im not going to take it anymore! Im mad as hell, and Im not going to take it anymore! Im mad as hell, and Im not going to take it anymore!

Howard Beale never existed; he was merely a character in the satire Network, one of the hit films of 1976. But he might as well have done, for many Americans were mad as hell in the 1970s, and every now and again, from quiet residential streets and spanking-new shopping malls, there were reports of people shouting, Im mad as hell, and Im not going to take it anymore! On college campuses, visitors sometimes saw leaflets being handed around: IMAHAINGTTIAM Midnight. And then, at the appointed hour, they would hear the clatter of windows being opened, and hundreds of youngsters would stick their heads out into the night and scream at the tops of their voices: Im mad as hell, and Im not going to take it anymore!

This book tells the story of why Americans became so mad, and why it mattered. It is the story of an extraordinary time in the nations history, a period of economic depression, political corruption, military defeat, and cultural introspection, but also one of unexpected popular protest and artistic vitality. It is the story of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, of stagflation, gas lines, and conspiracy theories. It is the story of the fall of Saigon, the collapse of dtente, and the revolution in Iran; of the Sunbelt, the Me Decade, and the Third Great Awakening; of Archie Bunker, Farrah Fawcett, and Bruce Springsteen; of Milton Friedman, Roger Staubach, and Phyllis Schlafly; of Roots, Hotel California, and The Deer Hunter.

At the time, many Americans did not know what to make of the 1970s. For one influential columnist, Joseph Alsop, they were the very worst years since the history of life began on earth; for another, Russell Baker, they were simply tiresome, their legacy an engulfing swamp of boredom. It was a decade that remained elusive, unfocused, a patchwork of dramatics awaiting a drama, wrote Times essayist Frank Trippett in December 1978. In the end, he decided that the 1970s would be remembered as a confused time, neither here nor there, neither the best nor worst of times, as free of a predominant theme as of a singular direction.

Parceling up history into ten-year chunks is merely a journalistic trick borrowed from the calendar, and it often obscures as much as it illuminates the past. There was more continuity between the 1960s and the 1970s, or the 1970s and the 1980s, than we often remember. The great historical trends, from the rise of the suburbs and the Sunbelt to the decline of racism and the changing role of women, did not stop and start with the changing of the seasons. When conservatives rail against the legacy of the 1960s, complaining about the collapse of discipline and the family, the rise of crime, and the spread of pornography, they are often talking about things that peaked in the 1970s. And the continuities run even deeper than that, for, as this book shows, many things that we imagine started in the 1970swomens liberation, the New Right, the culture warsactually had their roots in earlier decades. Every generation likes to think itself unique; in fact, the arguments people were having during the presidency of Jimmy Carter were often strikingly similar to those people had when Calvin Coolidge was in the White House.