Were living on time were having to borrow

No one knows if we will live to see tomorrow.

People will say, when they look back at today,

Those were the good old, bad old days.

Anthony Newley, The Good Old Bad Old Days (1972)

Howard turns and looks at Barbara, inspecting this heresy. He says: There may be a fashion for failure and negation now. But we dont have to go along with it. Why not? asks Barbara, after all, youve gone along with every other fashion, Howard.

Malcolm Bradbury, The History Man (1975)

RIGSBY: This country gets more like the boiler room on the Titanic every day: confused orders from the bridge, water swirling round our ankles. The only difference is they had a band.

Eric Chappell, Rising Damp (1977)

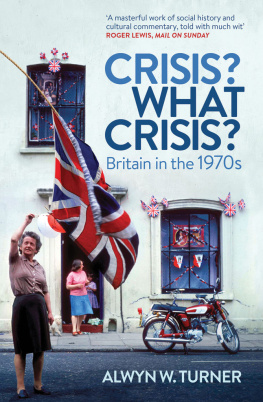

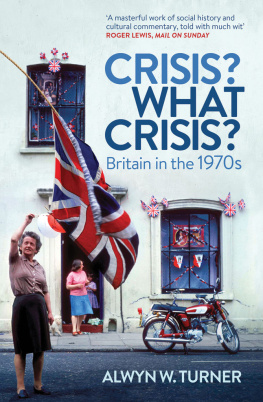

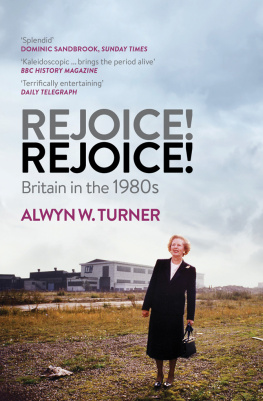

W hen originally conceived, this book was not intended to be the first volume in a series. But thats how it turned out. It has been followed by Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s and A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s, which continue the story of how the post-war consensus in British politics and society was finally destroyed, to be replaced by a new settlement, based on economic and social liberalism.

Running alongside that political narrative is another: the emergence of a cultural movement which was largely formed in the 1950s and 1960s. Manifest in film and television, fashion and music, this was initially seen as being primarily the preserve of the working class and of youth and therefore of little serious interest. Over the period described in these books, the phenomenon matured, revealing itself to be sustainable and capable of crossing age and class lines: youth culture became national identity. In doing so it intersected at crucial points with the world of politics, pre-empting, prompting and reflecting wider changes in the country.

When preparing this edition of the first volume in the trilogy, I have resisted the temptation to go back to the beginning and start again. The one exception is the final chapter. Since this was intended as a stand-alone book, I originally attempted to sketch in, very briefly, subsequent developments up to and including the Falklands War of 1982. Everything described in that chapter has now been treated more fully in Rejoice! Rejoice!, so I have cut much of the detail from here, and added instead a short note concluding on the decade.

Because the 1970s remain the subject of some dispute. Since the original publication of this book, there have been several other accounts of the period, and as the decade slips deeper into history, there will be further such works, through which a more settled version of the times will become established. It is to be hoped that what emerges will judge the era on its own merits, rather than seeing it only as an appendix to the 1960s or a precursor of the 1980s. In the meantime, the aim of this book, and its sequels, is to tell the story, insofar as it is possible, as it appeared at the time.

Alwyn W. Turner

June 2013

Intro

This is the modern world

T he lights were going out all over Britain, and no one was quite sure if wed see them lit again in our lifetime.

That, at least, was one version of the period between Edward Heaths election victory in 1970 and that of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, the watershed years that saw the end of one Britain and the first tentative steps towards a new nation. As the amphetamine rush of the 60s wore off, the country was confronted by a series of crises that set the tone for the remainder of the century and beyond: crises about natural resources, about race and immigration, about terrorism and environmental abuse, about Britains position within Europe and that of nationalisms within Britain, crises in fact about everything from street violence to class war and even to paedophile porn. It was a time when the certainties of the post-war political consensus were destroyed and it was unclear what would emerge to replace them.

For years afterwards, it was a decade that could scarcely be mentioned without condemnation, conjuring up images of social breakdown, power cuts, the three-day week, rampant bureaucracy and all-powerful trade unions. And then came the inevitable correction. In 2004 the New Economics Foundation constructed an analysis of national performance, based not on the traditional criterion of gross domestic product, but on what it called the measure of domestic progress, incorporating such factors as crime, family stability, pollution and inequality of income. And it concluded that Britain was a happier country in 1976 than it had been in the thirty years since.

For at least one generation, this was already common knowledge. To be young in that dawn might not have been very heaven, but sometimes it didnt seem too far off, despite the privations. The writer Philip Cato, who grew up in Rugeley in the West Midlands, commented that try as I might, I really cannot remember any truly bad times. Even when his father, a postman, became involved in a bitter and unsuccessful seven-week-long strike in 1971, it was far from a disaster as seen through a childs eyes. I was well chuffed, remembered Cato, because I was entitled to free school dinners which meant I was at the head of the queue in the canteen, clutching my little purple ticket with all the other kids whose dads were on the dole. Similarly, the record-breaking long, hot summer of 1976 may have caused all manner of problems for the countrys farmers, but for schoolchildren it was cherished as the time when head teachers were forced to admit publicly, in the first assemblies of the autumn term, that smoking actually existed, issuing warnings to be careful when disposing of cigarette butts.

By the time of that NEF research, the 1970s had also undergone a cultural reappraisal. No longer the decade that taste forgot, it was now seen as a golden age of British television, of popular fiction, of low-tech toys and of club football. The British film industry might have been in decline, but it was still capable of scaling new peaks with Get Carter, Performance, The Wicker Man. Even punk rock, which seemed at the time to be as limited in its commercial impact as skiffle had been twenty years earlier, had emerged as the only global rival to hip hop. Who would have predicted that in the twenty-first century, the legacy of the Sex Pistols would be more influential on new bands than that of the Beatles? Or that the prime minister would one day walk into his partys conference to the sounds of Sham 69 singing If the Kids Are United, as Tony Blair did in 2005? These things have become as significant in perceptions of the period as are the memories of political crises.

To some extent this is less a re-evaluation than a recognition of how significant they had been even at the time. In 1978 London Weekend Television launched a new series, The South Bank Show, to replace its existing arts programme, Aquarius. Presented by Melvyn Bragg, the new show announced that it was to cover the consumed arts, a term that embraced cinema, rock, paperbacks and even television. It was an acknowledgement of how far the revolution in popular culture had come, and the extent to which it now permeated everyday life.

The greatest impact was made by television itself. The first Social Trends survey showed that in 1971 the average Briton watched 18.6 hours of television a week; by 1978 that figure had risen to 22 hours. And this was a shared culture, reaching the whole of society, so that over 95 per cent of all social classes acknowledged that they spent a considerable amount of their leisure time as viewers. There were still only three channels available, but between them they produced that decade both Britains best-loved comedy act in Morecambe and Wise and its most revered sitcoms

Next page