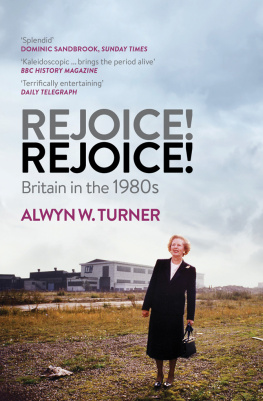

PRAISE FOR ALWYN W. TURNER

Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s

Put[s] into cold perspective what at the time we were too befuddled with emotion to understand... Turner has produced a masterly mix of shrewd analysis, historical detail and telling quotes... Indispensable

James Delingpole, Mail on Sunday

One of the pleasures of Alwyn Turners breathless romp through the 1980s is that it overflows with unusual juxtapositions and surprising insights... The tone is that of a wildly enthusiastic guide leading us on a breakneck tour through politics, sport and culture

Dominic Sandbrook, The Sunday Times

This kaleidoscopic history... provides a vivid and enjoyable guide to these turbulent years. Ranging broadly across popular culture as well as high politics...Turner brings the period alive and offers insights into both sides of a polarised nation

BBC History Magazine, Pick of the Month

Turners account of the 1980s is as wide-ranging as that fractured, multi-faceted decade demands... deft at picking out devilish details and damning quotes from history that is less recent than you think

Victoria Segal, MOJO

Turner does an excellent job in synthesising the culture and art of the day into the wider political discourse. The result is resolutely entertaining

Metro

Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s

Alwyn Turner has certainly hit upon a rich and fascinating subject, and his intertwining of political and cultural history is brilliantly done... This is a masterful work of social history and cultural commentary, told with much wit. It almost makes you feel as if you were there

Roger Lewis, Mail on Sunday

Turner appears to have spent much of the decade watching television, and his knowledge of old soap operas, sitcoms and TV dramas is deployed to great effect throughout this vivid, brilliantly researched chronicle... Turner may be an anorak, but he is an acutely intelligent anorak

Francis Wheen, New Statesman

An ambitious, entertaining alternative history of the 1970s which judges the decade not just by its political turbulence but by the leg-up it gave popular culture

Time Out

Entertaining and splendidly researched... He has delved into episodes of soap operas and half-forgotten novels to produce an account that displays wit, colour and detail

Brian Groom, Financial Times

Turner combines a fans sense of populism (weaving in references to a rapidly expanding popular culture) with a keen grasp of the political landscape, which gives his survey of an often overlooked decade its cutting edge

Metro

Fascinating... an affectionate but unflinching portrait of the era

Nicholas Foulkes, Independent on Sunday

So as you raise a glass to the Eighties tomorrow night, drink with me to the awakening of Britain. If it is to be a dynamic decade for us all, these will be difficult and dangerous years. But we are drinking to a country with a future.

Margaret Thatcher, New Years message (1979)

I pointed to the thriving stock-market our wealth-creating government had encouraged, the lads scarcely out of their teens making six-figure salaries in futures and commodities; she pointed to the inner-city slums, the unemployment figures, the bolshy pinched faces of underpaid nurses and teachers.

Terence Blacker, Fixx (1989)

MRS MIGGINS: So who are they electing when they have these elections?

BLACKADDER: Oh, the same old shower. Fat Tory landowners who get made MPs when they reach a certain weight. Raving revolutionaries who think that just because they do a days work that somehow gives them the right to get paid. So basically its a nice old mess.

Richard Curtis & Ben Elton, Blackadder the Third (1987)

Intro

This is the dawning of a new era

I t was, above all, a big decade, an era in which size became ever more important, when the people, events and debates of public life seemed to be written on a grand if not always a glorious scale.

It was a decade shaped by Murdoch and Maxwell, Schwarzenegger and Stallone, Heysel and Hillsborough, Live Aid and Lockerbie. Industrial conflict might have become less disruptive to the economy and to everyday life, but the strikes that did happen were epic in nature, with both the miners strike and the Wapping dispute lasting for a year apiece. Riots grew in both frequency and scale, as did demonstrations, some of which on Greenham Common, at RAF Molesworth and outside the South African Embassy in Londons Trafalgar Square became semi-permanent institutions. Union membership declined, but unions themselves began to amalgamate into larger entities, mimicking the mergers and takeovers that proliferated in the City of London. Even the Falklands War, minor in comparison with 1940, was considerably more serious than the Cod War against Iceland had been in the 1970s, and the period ended with Saddam Hussein threatening the mother of all battles if America, Britain and their allies continued in their attempt to remove Iraqi troops from Kuwait. For internationally too, it was a time of big, bold politics, a time for Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev to seek a resolution of the Cold War; it saw the rise of political Islam, the fall of the Soviet empire and, what was for some, the biggest story of all: the realization that human activity and industry might change the very climate of the planet, with uncertain but perhaps catastrophic consequences for the species.

Meanwhile, Dallas and Dynasty inspired the inflation of womens fashions and hairstyles, tours by pop superstars became bigger and more lucrative and were individually branded to enhance their commercial potential, while London having resisted for so long the vainglorious machismo of tall buildings finally sacrificed its skyline to a series of massive office blocks, from the NatWest Tower to Canary Wharf. Models mutated into supermodels, supermarkets into superstores, cinemas into multiplexes. Building societies became banks and humble record shops developed delusions of grandeur, turning themselves into megastores. High streets were eclipsed by out-of-town shopping centres, and the number of television channels, newspapers and magazines simply grew and grew. If something wasnt already big, then advertising one of the great growth industries of the time could make it seem so, or else the overblown price tag would suffice, as with the rise of nouvelle cuisine or the trend away from drinking pints in pubs towards bottled beers in bars.

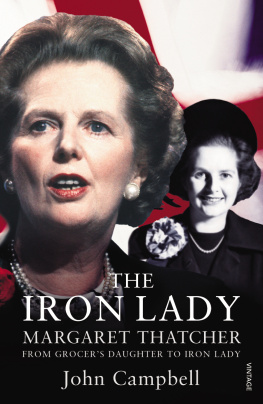

And in Britain this swollen, steroid-pumped decade was dominated by the figure of Margaret Thatcher, the unlikeliest of Conservative Party leaders, who set a twentieth-century record as the longest-serving prime minister. I was eighteen when she got in, wrote comedian Mark Steel, recalling Thatchers political demise in 1990, and now I was thirty. All that time. All that time shed strutted across my and millions of other lives, the symbol of every rotten selfish vindictive side of the human condition she could rake up and cultivate, like an evil scientist nurturing a test tube of greed and releasing it across the whole planet.

Clearly Steels views were not universally shared, for Thatcher won three successive general elections, but the sense of his whole youth passing him by under her rule was very common indeed. Because her long period in office coincided with the coming to political maturity of the most numerous generation in British history, a demographic bulge which had peaked in 1964, the only year that the birth-rate exceeded a million. So while nine million people were born in Britain during her term, somewhere around twelve-and-a-half million others found that, on the first occasion that they were entitled to vote in a general election, she emerged as the victor. For that generation, even more than for the rest of the country, she was the one figure who shaped political perceptions, whether for good or ill, in support or in opposition, well into the next century.

Next page