Foreword

Plus a change

Twenty-five years ago I returned from a four-year posting as chief US correspondent of the Observer . In 1987 Margaret Thatcher was in her pomp, about to win a third term of office. I wanted to explore again my own country, so I took notebook and pen and set out to report what I found. I travelled widely from Aberdeen and the already fading oil boom, via the dying, post miners strike, Durham coalfields, the north-west and a failing new town, sink estates, a successful comprehensive, the homes of affluent immigrants, the bolt holes of victims of race hate, the factory floor, the boardroom and the booming City wine bars immediately after the Big Bang.

I journeyed with an open mind. I was not bent on Thatcher-bashing, but I soon encountered aspects of British life that alarmed me (and alarm me yet more now). Already the poor were being blamed as in early Victorian days for their plight; to be poor was to have failed; those who could were being encouraged to shift for themselves in vital areas of public life like education; the NHS, buckling under the strain of an ageing population and vastly more expensive treatments and medicines, was becoming the political minefield it is today; the old industrial areas were bleak and declining our national crisis was that we were fast dividing into them and us camps, a vast gulf opening between comfortable and very uncomfortable Britain. The comfortable were taking it for granted that homeless people dossed down for the night in the doorways of West End theatres, while, riots apart, uncomfortable Britain was normally safely out of sight and mind.

Born in the 1940s, I belong to what has been dubbed the lucky generation. The cards were stacked in our favour: good free education, copious and stimulating job opportunities, affordable homes even for those on modest salaries, a coping health service and longer life expectancies than any previous generation. Our further luck was that, as we became adults, Britain grew more harmonious, more egalitarian, more civilized: it was good to live in these islands. The unity fostered by the second world war, when (within reason) all classes were in the same boat, and the benefits of the welfare state had combined to create a country at ease with itself. Of course, not everything was perfect. Trades unions and poor managements had between them rendered Britain uncompetitive. Millions of days were lost to strikes; innovation lagged; industrial complacency reigned. We had crafted effective political and industrial structures for our defeated enemy, Germany, but thirty-five years on we ourselves had failed to modernize. Something had to be done and someone had to do it. That someone proved of course to be Margaret Thatcher. By 1987 she was, by head and shoulders, the most significant player in Britain. It was her era, and she ruled the roost, bestriding every aspect of national life: young people who grew up during her reign as PM were dubbed Thatchers children.

She arrived on the steps of 10 Downing Street in May 1979 mouthing the emollient words of St Francis of Assisi: Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope. I already knew something of the lady, and these were not the sentiments I expected to hear from her lips. I had seen her at close quarters steamroller people with whom she disagreed. On the day of her first general election success I was on a beach in Florida trying to catch fish with my children. The local radio station opened its British election report the third item in the running order after traffic accidents with the news that actress Vanessa Redgrave (standing for the Workers Revolutionary Party) had failed to be elected to the British parliament. The newscaster had just time before an ad break to slip in the information that the United Kingdom had elected its first woman prime minister.

Back in London I reported on the first two years of life in Britain under her new government, before heading again for Washington and four years abroad. When I left, Mrs Thatcher was as unpopular as any PM had been in the early stages of an administration. It seemed likely that I would return to a Thatcherless Britain, breathing more easily after the trauma of her short regime. Unemployment was going through the roof, and manufacturing through the floor. The divisions between Briton and Briton, narrowing over the previous thirty-five years, were again widening. Harmony was not the word. However, in April 1982, I was in the office of Senator John Warner, one of Elizabeth Taylors cast-off husbands and a member of the US Senate Armed Services Committee, when he took a phone call. Your country is at war with Argentina, he said as he replaced the receiver. Mrs Thatcher entered those alarming months when the success of the Falklands conflict hung in the balance as a failing premier: she emerged triumphant, and the Iron Lady myth in the making had been born.

She swept back to office in 1983, and for the next seven years dominated British politics. Lord Hailsham, her lord chancellor, had coined the term elective dictatorship to describe the British constitutional arrangement whereby a prime minister with a large parliamentary majority can more or less do as he (or she) pleases although his target had been the then Labour government. Margaret Thatcher was, without doubt (as Tony Blair was to be a generation later), an elected dictator. What she said went: doubters were brushed aside, dandruff on the political collar.

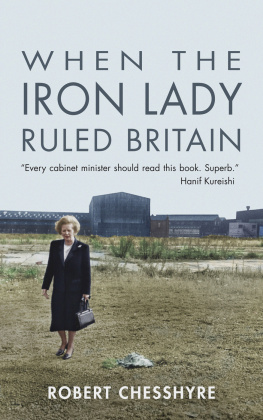

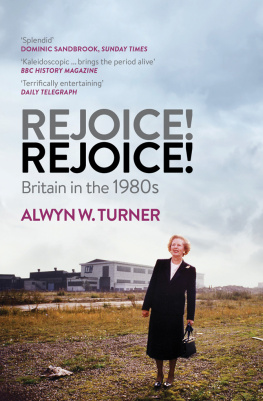

It was, therefore, the Iron Ladys Britain to which I came home. To speak ill of her was to commit (in many eyes) treachery, certainly lack of enthusiasm ran the risk of being condemned as unpatriotic. This book was attacked in a Sunday Times editorial (alongside work by Ian McEwan and Hanif Kureishi) as being smugly negative. We stood accused of gathering at favourite watering holes, where (even in such supposedly hard times) the Montrachet flows freely. If only. Our sin was to doubt. Rejoice, rejoice, Thatcher had exhorted the nation as the Argentinians were defeated. The mood persisted: Britain was, so Thatchers supporters proclaimed, on its way again. Those who were less than enthusiastic about our leader and who failed to rejoice were deeply unfashionable and if they knew what was good for them, implied the Sunday Times would do well to keep their thoughts to themselves.

Whatever ones views, it was impossible not to recognize that Thatcher was a phenomenal force blowing through British (and world) politics: through the sale of the more desirable council homes she put capital into the hands of a new class of person; she curbed (emasculated might be a better word) the unions; she wrapped the union flag tightly about these islands. But the way she did things was not always pretty, and even her devoted supporters had to acknowledge that she was deeply divisive. The current silly Marmite test you either love it or hate it has nothing on the Thatcher test. Indifference was not an option. I know people to this day who will not have a word said against her: to them she remains untouchable, on a pedestal with Winston Churchill. I know others who continue to blame her and her legacy for the ills of economic failure and social division that afflict us now. At one stage such people even blamed her (not always jokingly) for bad weather.

I have changed nothing in this book except the title, for what strikes me returning to my own return twenty-five years on is how far Britain has remained unaltered. Add a few noughts for inflation, and 1987 is still with us. The difficulties that beset us now, beset us then. Even the statistics are eerily similar three million out-of-work then, nearly three million out-of-work now, for example. The film, The Iron Lady a strangely crafted biopic, in which Thatcher, portrayed as a senile woman who labours under the delusion that her late husband, Denis, is still with her, revisits her life and career is far from accurate. But it does shine a light on her dominance, mistress of all she surveyed, in particular mistress of the pusillanimous Tory wets in her Cabinet. She vowed to go on and on and on, and in 1987 it was easy to believe that she might. One myth, perpetuated by the film, is that Mrs Thatchers origins were ever so umble; if not born in a cardboard box, she nonetheless had had to climb a very greasy pole. The Iron Lady shows her serving behind the counter of her fathers grocers shop in Grantham. When Thatcher became Tory leader, I interviewed her prudently low-profile sister, Muriel, an Essex farmers wife who pooh-poohed this image. Our father had destined Margaret for Oxford, and she would sweep through the shop with her school books under her arm past the girls he employed to serve the customers. Thatcher may not have possessed swathes of Scotland, as had previous Tory leaders, but her father was mayor of Grantham, alderman, chairman of the grammar school governors, politically successful in the local milieu and fiercely ambitious for his clever daughter. He actually owned two shops. Her disadvantages were exaggerated (as were John Majors some years later) for political ends. She was from many rungs further up the social ladder than her hated predecessor, Edward Heath. She certainly didnt fool the people I met on my journey round Britain, who saw her with her son Mark at Harrow and a hereditary title for her husband most certainly as one of them rather than as one of us.