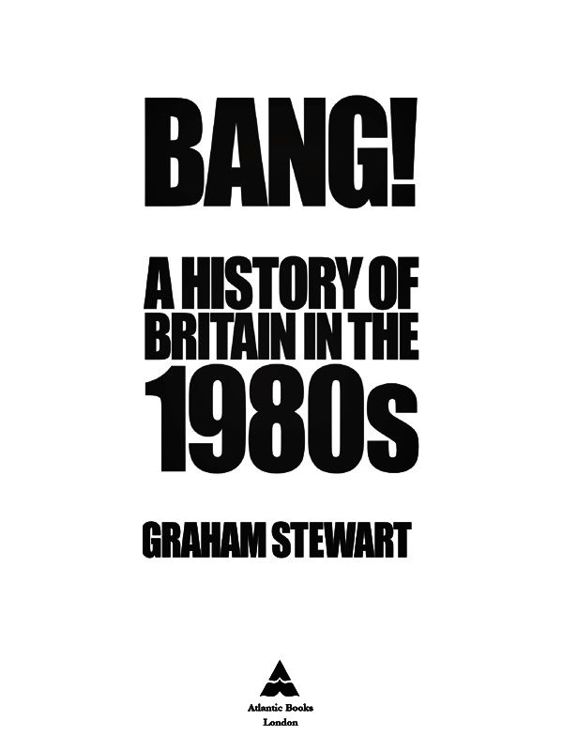

Also by Graham Stewart

Burying Caesar: Churchill, Chamberlain and the Battle for the Tory Party

His Finest Hours: The War Speeches of Winston Churchill

The History of The Times (Volume VII): The Murdoch Years

Friendship and Betrayal: Ambition and the Limits of Loyalty

Britannia: 100 Documents That Shaped a Nation

Published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Graham Stewart, 2013

The moral right of Graham Stewart to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781848871458

Ebook ISBN: 9781782391371

Paperback ISBN: 9781848871465

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my good friend, Jean-Marc Ciancimino

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Britain in the 1980s does not lend itself easily to dispassionate analysis. It was a time of primary colours, clashing ideologies and divisive personalities. Any effort now to dodge contentiousness by painting it in gentler, pastel shades can only miss its vibrant power to shock, disturb and excite. Rather than skirt around its arguments, the historian can only join them.

At the same time, I am conscious of the dangers of allowing personal experiences of the decade to cloud judgment. For this reason I have tried to let neither my own partial and perhaps hindsight-contaminated recollections (I was a Scottish teenager for almost all of the eighties) nor the possibly unreliable memories of those who shaped the period, rather than merely grew up in it, assume undue influence. Wherever possible, it is always best to garner the evidence from what is recorded during, or soon after, the events.

For their help in gathering this material I should particularly like to thank Eamon Dyas and Nick Mays at the News International Archive and Record Office and the staff at the London Library and the British Library for all their assistance. Any historian of the politics of the period is also indebted to the Margaret Thatcher Foundation, whose exemplary website provides an easily accessible treasure trove of primary material.

Among the secondary sources that have most influenced this book, I should like to single out John Campbell for his remarkable two-volume biography of Margaret Thatcher, Francis Beckett and David Henche for their history of the miners strike, Ivor Crewe and Anthony King for their work on the SDP, Simon Reynolds on early-eighties pop, Matthew Collin on the late-eighties dance scene and David Kynaston for his magisterial study of the City of London. The responsibility for the interpretations drawn from these and other works of scholarship listed in the bibliography is, of course, entirely my own.

At Atlantic Books, I consider myself extremely fortunate to have had Toby Mundy as my commissioning editor, while James Nightingale expertly saw the book through from manuscript to printing press. As ever, my agent, Georgina Capel, has been a tireless advocate and supporter.

Finally, for their kindness, encouragement, ideas and stimulating conversation during the writing of this book I would particularly like to thank Nicholas Boys Smith, Jane Clark, Mark Craig, Thomas Harding, Daniel Margolin, Duncan Reed, Luke Rittner, Cita and Irwin Stelzer, Paul Stephenson, Eleanor Thorp, Edward Wild and Nicole Wright. Jean-Marc Ciancimino has been a very good friend over many years and it is in recognition of this that I should like to dedicate this work.

ILLUSTRATIONS

First section

Second section

Third section

Fourth section

Graphs

INTRODUCTION

The paradox of the eighties is simply put. Everywhere we look around and see its profound influence and yet the decade itself its tastes, obsessions and alarms is beginning to seem remote to the point of becoming exotic.

The realization that Britain in the eighties did not, in fundamental respects, resemble the country of today presents an opportunity worth grasping. It suggests that we are gaining distance and critical detachment from events and personalities that divided opinion to a degree that seemed remarkable even at the time. Of course, it is the extremes and peculiarities of any age that tend to be remembered while the quiet continuities remain unexamined or taken for granted. Some Britons rioted and went on protest marches while others hung patriotic bunting and bought shares in British Telecom. Impervious to stereotype, a few may have done all four. Many more did none of these things; history may be shaped by trendsetters but is not just inhabited by them. With the help of selective, and at times repetitive, archive footage to accompany television and newspaper commentary, shoulder pads and striking miners are portrayed as emblematic of the eighties. At the same time, sales of denim jeans held up pretty well and millions of employees simply got on with their work and, every once in a while, won promotion.

Nevertheless, it would take an essayist of wearisome contrariness to argue that the period of the eighties had little that was distinctive, let alone unique, about it and should be conceded no meaning beyond that dictated by the calendar. For a start, no decade had seen Britain served continuously by the same prime minister since William Pitt the Younger in the 1790s; and unlike Pitt (whose terms of office stretched from 1783 to 1801 and 1804 to 1806), Margaret Thatchers Downing Street tenure (1979 to 1990) almost perfectly framed the intervening decade as if it were her own. Perhaps this might not have been so significant had she possessed a more technocratic and less commanding personality. That she proved to be one of the dominant figures of modern British history is a defining characteristic of the period. While this book encompasses politics, economics, the arts and society, it has a unifying theme: the attraction or repulsion, in each of these areas, to and from the guiding spirit of the age. That Thatcher was the personification of that spirit is perhaps the least contentious aspect of what will unfold.

There is another recurring theme. It is that what happened during the eighties in the UK was not just significant for those who lived there. The countrys influence was worldwide to an extent that is easily forgotten in the first decade of the twenty-first century. The Cold War and the major strategic role of British forces in defending the Free World against the Soviet Union stand out with particular clarity. Thatcher was the first Western leader to identify Mikhail Gorbachev as someone with whom, to paraphrase her, business could be done. She was an important bridge between him and Ronald Reagan. The legacy from that most fruitful of dtentes was of unambiguous benefit to mankind, which for the previous four decades had been forced to ponder what, at times, looked like its imminent destruction in nuclear war. Necessarily, though, the cold thaw diminished Britains strategic significance in the world.