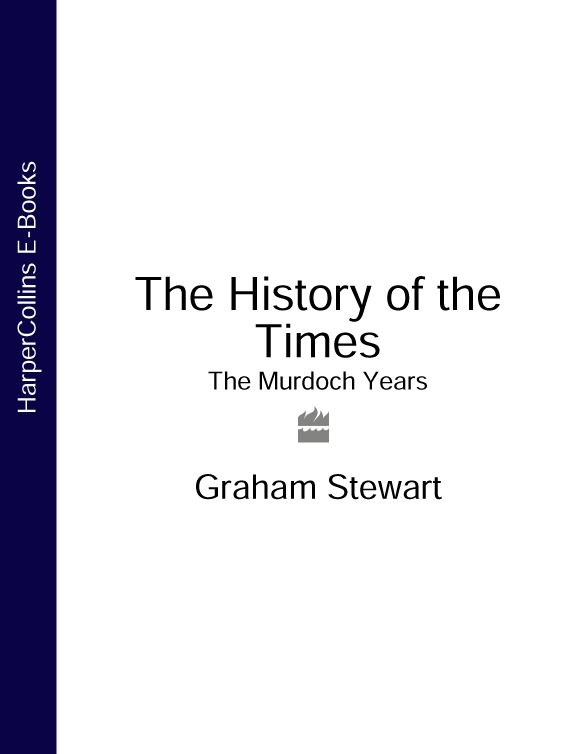

This is an official history. It has access to private correspondence and business documents that have not been made generally available to other writers or historians. Some may consider this a mixed blessing and assume that the consequence must necessarily in the words of the accusation that used to be labelled at The Timess obituaries sniff of an inside job. It should therefore be stated from the first that at no stage has anyone altered anything I have written or pressured me into adopting a position or opinion that was not my own. It is an official history but not a formally approved or authorized version of events.

Indeed, Rupert Murdochs relaxed attitude while I probed around in an important part of his business empire contrasted favourably with past precedent in this series. Those commissioned to write the six previous volumes of the official history of The Times were closely involved in the papers life, a conflict of interest that certainly hindered the appearance of objectivity. The first four volumes, covering the period between its foundation in 1785 and the Second World War, were compiled between 1935 and 1952 by a team under the command of Stanley Morison. Morison was the inventor of the worlds most popular typeface, Times New Roman. He was also a close friend of the papers then owner, John Astor, and its editor, Robin Barrington-Ward, who went so far as to describe Morison as the Conscience of The Times. Iverach McDonald, who was an assistant editor and managing editor of the paper during the period he described, wrote volume five in 1984. Volume six, covering the years 1966 to 1981, was written in 1993 by John Grigg. He had been the papers obituaries editor between 1986 and 1987 and was a regular columnist. Grigg, at least, was not directly involved in the events about which he wrote. Instead, he brought the insight and flair of the independent historian of note, attributes for which he will be fondly remembered. For my own part, I cannot claim much personal involvement with the paper during the years covered in this volume. My only first hand experience was garnered during the year 2000, when I was a leader writer. As a historian, my specialist area is British politics in the 1930s.

The Times is not, first and foremost, a national institution. It is a business. Yet I have avoided the temptation to treat it purely as a corporate entity, as if its journalistic and literary output had no more cultural significance than the manufacturing of the paper on which it was printed. Consequently, I have described its journalism within the context of the world events that were its stimulation. The book, therefore, is part business history, part work of reference, part anthology. It is intended to appeal both to those interested in the paper in particular or journalism in general who want to know how The Times conducted itself during the period 1981 to 2002.

The book would not have been possible without the knowledge and assistance of The Timess archivist, Eamon Dyas, and his assistant, Nick Mays, at News Internationals impressively organized Archive Centre and Record Office. Elaine Grant and Karen Colognese were unceasingly helpful in providing assistance from the chairmans office. Journalists too numerous to mention here have accepted my invitations to share what they know over some light refreshment. Their recollections and observations have made this book a pleasure to write. It has also been a relief to discover that the traditions of the Fleet Street lunch are not entirely a thing of the past. It is not the place of an official history to indulge the sort of convoluted tales of uncertain provenance that enliven many a hacks memoir of the Street of Shames alleged glory days. Nonetheless, despite my preference for primary evidence, I have not omitted gossip where I have been able to cross reference the story and establish its basis in fact. Any errors or misrepresentations remain, of course, entirely my own.

Among the many individuals that have helped me, I should like in particular to thank Richard Spink and Tasha Browning for their indefatigable generosity of spirit. At HarperCollins, Annabel Wright has been a stalwart aid. I have profited enormously from the valuable suggestions made by Andrew Knight and Brian MacArthur whose experience of the newspaper world is exceptional. Rupert Murdoch gave me a considerable amount of his time and I appreciate the unconditional assistance he has given me. I should especially like to thank Les Hinton, executive chairman of News International, who has been a great friend of the project and unfailing in his support and enthusiasm. It is my regret that Sir Edward Pickering, grand old man of Fleet Street and executive vice-chairman of Times Newspapers, did not live to see the completion of the book he commissioned and for which he provided such sagacious advice. I dedicate it to his memory.

Graham Stewart, February 2005

CHAPTER ONE

A LICENCE TO LOSE MONEY

The Problems of Owning The Times;

the Thomson Sale and the Murdoch Purchase

I

On 22 October 1980, in its one hundred and ninety-sixth year, The Times was put up for sale. It would be closed down if no suitable buyer secured a deal before 15 March the Ides of March. Staff received notice that their contracts were being terminated.

Superficially The Times was a prize, but few who had studied the accounts would have thought so. It resembled the sort of Palladian mansion still occasionally offered for sale through the pages of Country Life. Despite the odd seedling protruding from the cornicing, the exterior still looked magnificent and the asking price seemed preposterously low. But those enquiring beyond the inventory of rare and exotic contents (to be auctioned separately) soon discovered why the previous owners no longer felt able to comply with the conditions of this national treasures preservation order. The lead had come away from the roof, the attic floorboards had collapsed and damp enveloped what had once been a ballroom. The costs of upkeep would be punishing and, with little prospect of a change of usage permit, the likely revenue insufficient. On hearing the news that The Times was for sale, the reaction of Rupert Murdoch, the owner of the Sun and the News of the World, was reported in the press: I doubt whether there will be any buyers.

It was certainly a bad sign that the share price of the Thomson Organisation, The Timess owner, soared by 40 million on the announcement that it was offloading its flagship paper. This was particularly alarming since for sale was not only The Times and its three smaller circulation supplements but also the Sunday Times, a paper that had been profitable for seventeen out of the past twenty years. But the Sunday market leader had lost 300,000 copies through industrial action the weekend before Thomsons announcement In the same interview in which he declared little interest in picking up the bill, Rupert Murdoch was quoted as describing TNL as a snake-pit.

It was hard to see what hard-headed businessman would leap at the opportunity to enter this environment. Certainly, there would be bidders with an interest in either asset stripping or wanting to turn The Times into a private toy. Middle Eastern backers expressed interest but, as Sir Richard Marsh, chairman of the Newspaper Publishers Association (NPA), indelicately put it: I think [the idea of] The Times being owned by somebody in the Lebanon would be a joke.

In Westminster there was cross-party alarm. Michael Foot, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, who had once been one of Beaverbrooks sharpest pens, declared every journalist in the country, I would think, would be deeply shocked at hearing the news that