The narrow road twists up a ravine past a clattering mountain brook and quiet ponds. Blazing clumps of azalea and dogwood partially screen tall stands of oak and tulip poplar behind. Deer browse in the underbrush. Birds sing. Bees hum. No wonder Hollywood chose these woods for the setting of a production of The Last of the Mohicans.

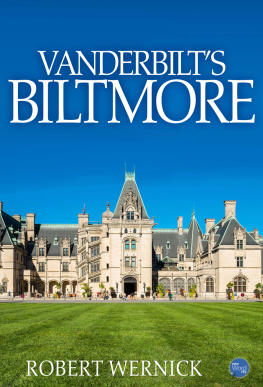

Like a Hollywood sound-stage, it is all manmade. Thousands of trees and bushes were put here in the 1890s by Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New Yorks Central Park, in order to create an aspect more nearly of a subtropical luxuriance than would occur spontaneously in the southern Appalachians. And, at a turn of the long road beyond them, he decreed that wilderness should give way to a complex of formal gardens, in the middle of which would stand, as it stands this day, an enormous chateau with high-pitched roofs, dominating the North Carolina countryside all the way to Mount Pisgah, seventeen miles away.

The chateau, the gardens, the azaleas, and the million and a half or so trees are here all because a young man came riding through the countryside one day in the late 1880s. It was a very different countryside then, a sorry stretch of over-logged, overgrazed, plowed-over bottom lands and hillsides, its soil cruelly eroded. But George Washington Vanderbilt, vacationing in Asheville with his mother, saw a chance to turn into a luxuriant thriving country estate like those he had visited and admired in Europe.

He was still a bachelor, but the house would be big enough to bring up any family-to-be in a setting of aristocratic comfort. He would be able to raise cattle and crops, ride and hunt and fish, and all his friends could come for repose and entertainment. He would call the place Biltmore, from Bildt, the little Dutch farming village from which his ancestors had emigrated to Staten Island, and more, an Old English word for rolling uplands.

Being a Vanderbilt, George had little financial difficulty in taking the step from vision to reality. He was the youngest of the nine children of William Henry Vanderbilt, head of the clan since the death of Cornelius, nicknamed the Commodore, for the great nineteenth century fortune he amassed from steamships, railroads, and shrewd practices. Georges share of the family fortune was modest, estimated to be around $10 million, but, at a time when an average city household had an income of $573 a year and flour cost three cents a pound, $10 million could do very nicely.

In the 1880s, the Vanderbilts were still regarded as new money, pushy upstarts compared to people like the Astors, who had made their fur-trading fortune a couple of generations earlier. The Vanderbilt urge for monumentality was considered a sign of their vulgar nature. They all had a weakness for bigger and better, beginning with the Commodore himself, who built a large house for himself on Staten Island, but he soon decided that it would be better for his business and social aspirations to live in a bigger one in Manhattan. When his wife, Sophia, balked at leaving her quiet island community, he had her clapped into an insane asylum until she came to her senses.

The Commodores descendants liked to build for posterity. Georges father constructed the Metropolitan Opera House, and William K., Georges brother, erected Grand Central Station. Georges niece, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, would found the first museum of contemporary American art. But mostly they built for themselves, creating chateaus on Fifth Avenue or on the Hudson River or in Newport, where they could show off the glittering luxuries that went with new money in the nineteenth century.

George was well acquainted with grand homes long before he came to Asheville. He grew up in his parents Fifth Avenue mansion. He inherited and remodeled a summer house in Bar Harbor, Maine. But he had the urge for something grander and more identically his own. He did not want to be cooped up in a corner of a city block, or in the paltry eleven-acre plot in Newport, where his brother Cornelius was building a seventy-room house, The Breakers. So that the name Vanderbilt would not send prices skyrocketing, he set a troop of agents to work quietly buying up land in North Carolina, and, by 1880 at the age of twenty-eight, he was well on his way to acquiring the 125,000 acres he desired. Then he got to work designing a house to stand on it.

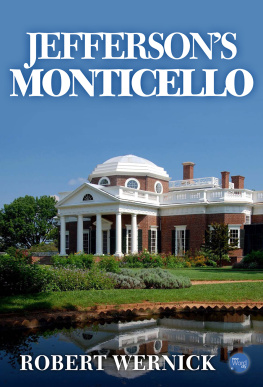

A natural choice for architect was his friend Richard Morris Hunt, who had already left his mark on the American landscape with the base for the Statue of Liberty and the Tribune Building in New York. Hunt was a grand master in the style of the cole des Beaux Arts in Paris, which dominated the Western world in the days before World War I. The puritanical early twentieth century would dub this style eclecticism, and, for many decades, no one with any pretension to be up to date would dare to say a good word about it. But now that eclecticism has been rechristened postmodernism, it has become intellectually respectable to cast a fond eye on these ornate, theatrical structures, to sympathize with the admiration which George Vanderbilt felt for the ebullient, self-confidence of Hunts design for Biltmore.

His original sketch for the house was a modest Tuscan villa. However, in the course of long discussions and correspondence with his patron, ambition took wing, and the design became more and more grandiose. The house would swell to 225 rooms to become, until 2012, the worlds largest residence ever built for a private citizen (it has now been topped by a twenty-seven story, 400,000-square-foot home built by a billionaire in Mumbai, India).

The style of the exterior was tried and true French Renaissance, combining the classical sobriety of fifteenth-century Italy with the decorative exuberance of old-fashioned French gothic. The outside of Biltmore is made up of variations on a number of chateaus, notably the jewels of the Loire Valley, Blois, and Chambord. Inside is a rich jumble from a variety of periods throughout Europe and Asia. The taste of the day saw nothing odd in mingling sixteenth-century tapestries with modern paintings, a room full of Louis XV furniture next to one chock-full of Chippendale. Hunt designed some of the furniture himself.

In the vast hall called the Gallery, George Vanderbilt, a young man with brooding eyes and a long face, stared out from a portrait by John Singer Sargent. He was a sport among Vanderbilts, an intellectual who could read eight languages. He had studied land management and the history of art. He had visited the art treasures of Europe, not just to collect them but to learn about them. He commissioned portraits of Hunt and Olmsted for his walls, portraits that were considerably bigger than his own. But he was very much a part of the designing process at Biltmore. He was, Olmsted once said, a delicate, refined and bookish man with considerable humor and shrewd, sharp, exacting, and resolute in matters of business.

When Hunt proposed gracefully carved legs for chairs he was deigning for the seventy-foot-high Banquet Hall, Vanderbilt insisted on more manly straight legs. He wanted this hall to look like the nave of a church, and Hunt designed some giant organ pipes for one wall. They were attached to no organ, but the effect was undeniably grand. When it was proposed that local pine might be good enough for the floors in the servants quarters upstairs, young Vanderbilt scrawled a vigorous NO in the margin. Everything in Biltmore was to be first class and all its wood floors oak.

Complete with a vast wrought-iron chandelier that hung down through three stories of the central stairwell, and the thirty-odd master switches that controlled the flow of electricity, the place might seem more like an ocean liner than a private home. It was rumored locally that if all the electricity at Biltmore was to be turned on at once, the trolley cars in Asheville would grind to a halt.

Next page