This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING www.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1944 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2013, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

REGIMENTAL UNIT STUDY NUMBER 2

THE FIGHT AT THE LOCK

Published by History Section, European Theater of Operations

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

FIGHT AT THE LOCK

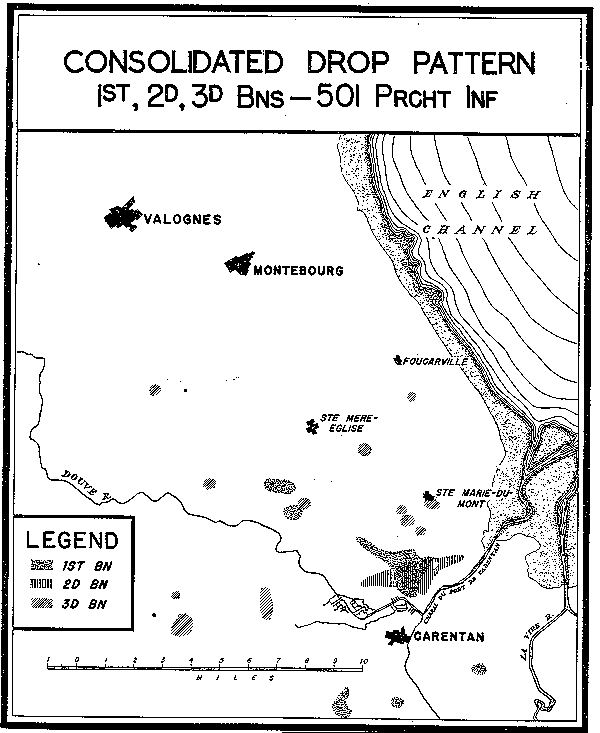

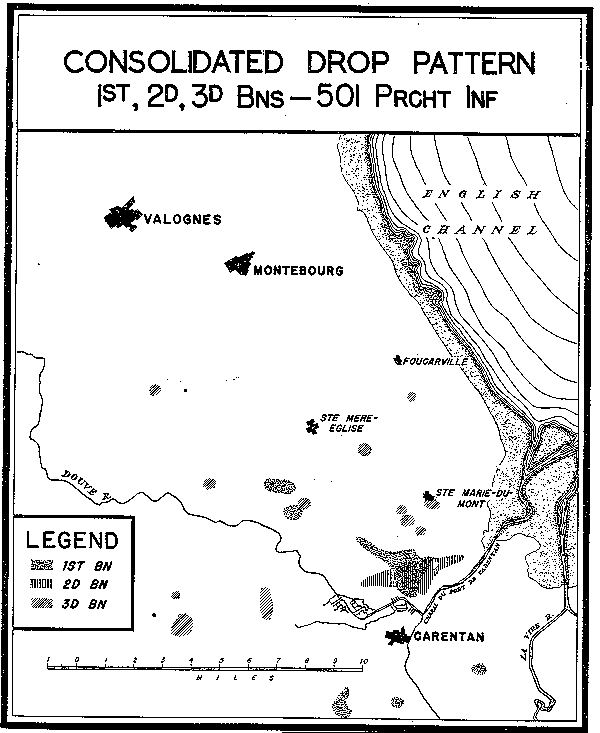

According to plan, the D Day objectives of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment were well concentrated. After dropping into Normandy a little to the north and east of the city of Carentan, the regiment was to press south and westward and establish the defensive position in this direction. In detail, it was to secure the line of the lower Douve River, first by seizing the strategic lock on the Canal De Vire Et Taute at Le Barquette and then by blowing the river bridges. In that way, it would stand ready either to assist the advance of American forces from out of the Utah Beachhead and to the westward or to fend off any German counterattack from the eastward.

From the beginning, American attention was directed at the Le Barquette lock. This unique objective and its possible military application appears to have fascinated the imaginations not only of those who planned Operation Neptune but of the commanders who were to execute it. To get to the lock first and to make certain that the enemy would have no use of it became an overriding consideration with the planning and tactical forces. Whether that interest was out of proportion to the strategic significance of the lock was a question never fully answered in the doing. American apprehensions as to what might happen if the Germans gained control of the lock superinduced one of the boldest strokes of the Normandy campaign, a stroke boldly made and tactically productive. Yet whether the emphasis placed on the position by the Allied planners was justifiable was never confirmed by the attitude of the enemy.

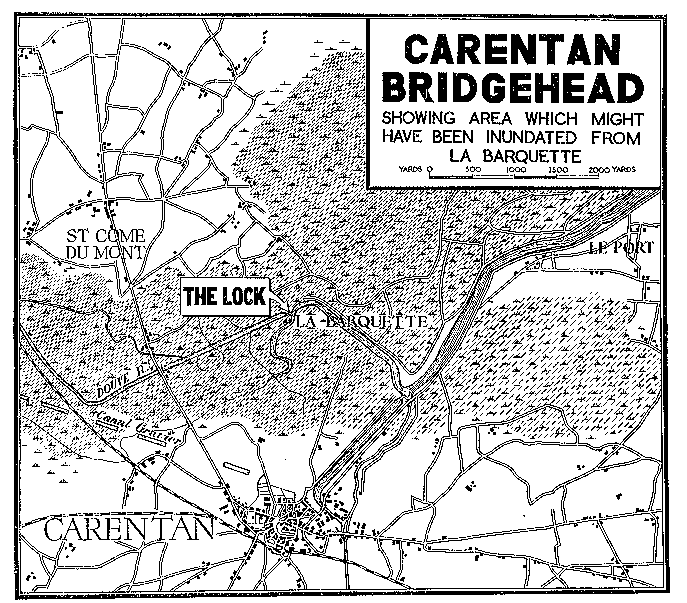

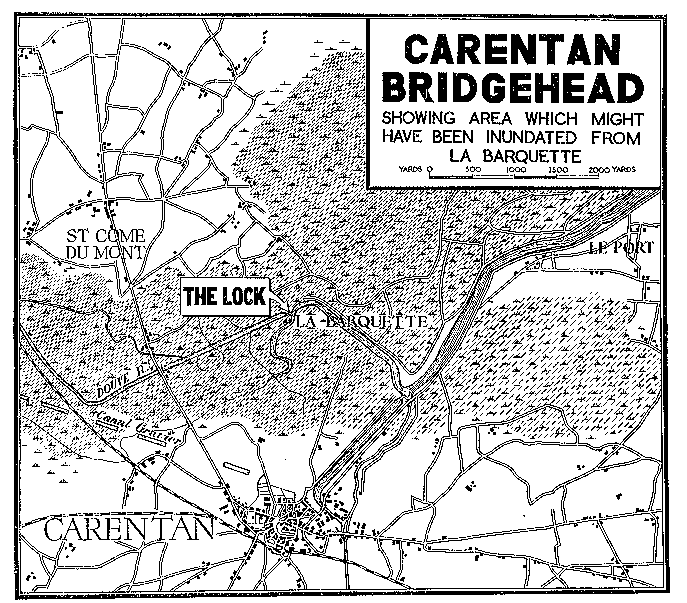

The lock at Le Barquette is below Carentan as the River Douve flows and near the confluence of the river and the largest of its canals. On 6 June 1944, this was the strategic importance of the lock that at high tide the low marshland around Carentan are below the level of the sea. The lock holds back the tide. If the lock is opened or demolished, the sea pours into the bottoms and the marshy water barrier to the east and north of Carentan become a salt lake.

Periodically in the years when the RAF had this area under observation, the Germans had opened the lock. Thereby the flood plain had become inundated so that a long arm of the sea interposed between the ridges of high ground around St Come Du Mont and the solid but somewhat lower ground skirting Carentan on the south and west. Air photographs had shown the extent of these inundations.

It seemed therefore that the device which the enemy had practiced might be turned against him. If the airborne could seize the lock intact and hold it against all counterattack by the enemy, we could use it as we willed. In case the enemy forces to the eastward rebounded strongly against the BEACHHEAD, the marshes around Carentan could be turned into a lake, imposing an extra barrier between the Germans and ourselves. Or we could sit on the lock and keep the marsh draining until we were ready to go forward.

The blowing of the bridges along the causeway crossing the River Douve and its canals east of Carentan was part of the same idea. The causeway provided the one convenient path across the flood plain. Even that path would be denied the enemy if the bridges were down.

Such were the main objectives of the regiment. Once these things were done and the line to the south-westward was made reasonably secure, the regiment was also to capture the town of St Come Du Mont and blow the railroad bridge across the Douve to the west of it. For these tasks, only two battalions were to be present, Third Battalion having been designated as the Division Reserve. Yet due to the misfortunes and miscalculations of the air journey and drop into Normandy, even this force was gravely depleted before the combat opened.

First Battalion and the Regimental Headquarters were in the leading serial of the regiment, with Second Battalion coming next serials 8 and 9 of the Division formation. By a fluke, a part of the leading serial, including the regimental coriander, dropped nearly on the right ground. The rest of the serial was scattered so badly that during the first stage of the operation First Battalion could not function as a tactical unit. A number of the sticks were unloaded south of Carentan, much deeper into enemy territory than was supposed to be encompassed by the initial Allied attack. Later the battalion commander was found dead in that area. The battalion executive became missing. All company commanders were missing though one regained the American lines five days later. Vanished also was the battalion staff though the S-1 and S-4 finally found their way back to the regiment. As a result of the drop, the battalion was wholly leaderless and its men far-scattered.

ONE COMMANDER'S EXPERIENCE

Col Howard R. Johnson rode in the leading plane of his regiment. All went smoothly as the formation crossed the Channel. In Johnson's plane the men let out a yell as they saw the French coast and most of them stood up and made a final adjustment of their equipment as the planes flew on and crossed the coastline. Halfway across the Cotentin Peninsula the formation ran into a scattering flak; it did no damage and the men paid little heed. About two minutes out from the Drop Zone, there was a strong build-up of enemy ground fire and the tracers arched up all around the formation. The troops got the first warning signal, then the green light. It flashed back through the astral dome from the lead plane to the others and the men jumped all except the men in Johnsons plane. At that critical moment a bundle became jammed in the doorway and for what seemed a much longer time but was by Johnsons later estimate about one-half minute, none could get out. They pushed frantically at the bundle. It dropped off into space and the men followed as swiftly as they could, feeling that they had overshot the mark. That 30-second delay was their salvation. For it enabled them to make a bullseye on Drop Zone D. Johnson figured afterward that his men who had jumped at the signal probably landed in the vicinity of St Come Du Mont and that many of the men who never rejoined the regiment must have come down in the marshes near Carentan and drowned before they could come free from their chutes.

Next page